James Somper

What do you think of when I say the word “chaos”? Everyone has their own definition and idea of what chaos is. For a parent of 3, chaos is the school run in the morning, as they attempt to get 3 (usually unruly) children out of the house, into a car, and then into a different building, where they are someone else’s problem for 8 hours. For the busy sales worker, it is the rush of people flying into the shops, with items flying off the shelves at a seemingly random (yet ever increasing) rate. For many, the Christmas period exemplifies chaos. The rush to get all the gifts one needs for all the people one cares about; the attempt to get all the decorations down from the attic and then put them all up, only to discover that half the lights no longer work; the full time job to prepare Christmas dinner on the big day which seems to have the ability to take the entire morning, no matter how prepared one is prior to it. The list is simply endless. However, what if I then asked you to narrow down your definition of chaos?

Most people fall into one of two categories when asked to define exactly what counts as chaos.

There’s a group that subscribe to the idea that chaos is synonymous with randomness. To these people, something is chaotic if one cannot predict what will happen next with any reasonable amount of certainty. Hence, flipping a coin a certain number of times would not be chaotic, because one could very easily work out the probability of each of those outcomes, even if the outcomes themselves are random. If we change the problem instead to a situation where 1 of 100 things could occur, with no fixed way of knowing the probability of any of those events, then suddenly the word “chaos” starts to creep in. Consider the situation where I have lost an important letter in a bunch of identical envelopes, and there are 100 envelopes to look through, except that’s been mixed with another 1000 envelopes and I only have 20 I can open before Royal Mail gets really angry at me and asks me 1) who I am 2) how I got in their mail sorting facility and 3) if I could please leave. If you would call this chaotic, then you likely fall into this first category.

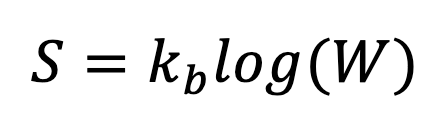

The second group takes a slightly more subtle approach to what chaos is. In a slightly tautological statement, they would claim that “chaos is a lack of order”. To these people, chaos becomes synonymous with entropy, which is a measure of disorder in a system. There exist many definitions of entropy, but statistical entropy was defined by Ludwig Boltzmann as:

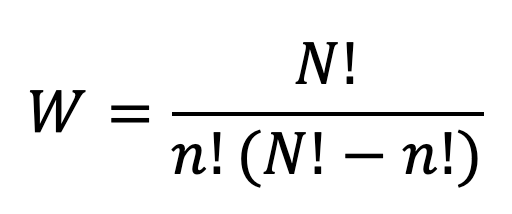

Where S is the entropy of the system, kb is the Boltzmann constant and W is the number of configurations the system can adopt, which is given by the Maths of combinatorics as:

if the n objects are identical, and there are N places one could position them. The larger W is, the larger S is, and therefore the more chaotic the system is considered to be. In my example with a now increasingly angry postal service, subscribers to the entropy = chaos argument would not describe the situation as chaotic due to the difficulty with which one can work out the chance I will find my letter, but rather because the number of ways my letter can be arranged in the pile of envelopes that security now won’t let me touch is so large, which means its entropy is so high, that therefore it is highly chaotic. To this group, it isn’t the difficulty of prediction that makes a system chaotic, but the sheer number of possible outcomes that renders it chaotic.

If one were to ask a mathematician to define chaos, they would likely either show or draw you this picture:

But apart from having likely consumed all the remaining ink in the pen that the mathematician used to draw it, and making you regret ever having asked, what does this tell us about what chaos really is?

Chaos, to mathematicians, has a more subtle, yet wonderful definition. It also manages to capture the two ideas about chaos that have been presented thus far. Mathematical chaos, in a sentence, is a system in which a small change in the initial conditions leads to a large (often unpredictable) change in the output. Thus, both groups are right, in a way.

The envelope situation above is pseudo-chaotic, as the probability of me finding my letter is very low, and relatively hard to calculate, although not impossible, but since Royal Mail have declared me public enemy number 1 and I now have a court order that bars me from coming within 10 miles of a post office, the probability has rapidly approached 0. However, the system is not chaotic, as a small change in the initial conditions (for example, adding one extra envelope) would not drastically change the output of the system (either way, I’m still not finding my letter). There are, however, many systems that occur in the natural world that are truly chaotic in nature.

Firstly, fluid turbulence. This kind of system occurs when two fluids that are travelling in opposite directions collide. Some examples of fluid turbulence are smoke clouds, ocean waves, and airflow over an obstacle (such as a sail in the video below).

These systems are notoriously difficult to model well, as small changes to the initial conditions of the velocity of each section of the fluid can lead to massively different behaviours. This makes them very hard to study, as there is no easy formula to predict what will occur when two waves collide. However, understanding these models is very important, as fluid turbulence in the ocean is a process that results in CO2 being trapped in the water where it then dissolves. Hence, if we want to have reliable and useful models for carbon capture in oceans, and by extension, climate change, we must face chaos head-on.

Secondly, weather forecasting. Weather forecasting relies on an intimate understanding of all the processes that cause our weather, ranging from wind pressure to cloud formation, and atmospheric movement. However, as stated earlier, the movement of fluids (such as smoke, and by extension, clouds) comes under an example of a truly chaotic system. This means that weather forecasting becomes incredibly difficult, as small changes or inaccuracies in measurements leads to massive changes in the final conditions. And yes that does begin to explain why the weather forecasters never seem to be able to get it right (they are trying, I assure you, the problem is simply akin to trying to convince a very angry hurricane to play nice!).

Finally, the solar system. The very place we spend our entire lives (and deaths) is a classic example of a chaotic system. The solar system can just be considered to be a large collection of spheres that interact. In mathematical terms, this is referred to as an “N-body problem”, which is inherently chaotic. There exists no general closed form, which is to say, there is no function that will perfectly describe the position of all N bodies at any arbitrary time for N ≥ 3.

As the solar system has a lot more than 3 bodies (although interestingly, the classically studied 3 body problem concerns the motion of the Sun, Earth and Moon), it becomes incredibly hard to predict the motion of objects, especially if their mass is relatively small (which means they move rather quickly). As the system is chaotic, “a small change in the initial conditions leads to a massive change in the output”, and so, if the measurements for the velocity, position, mass, or any other variables of a meteor are out by even a tiny amount, which they will be as one can only ever have measurements that are as accurate as your instruments will allow, we see a massive change in the output of the system. This leads to the phenomenon where meteors that are predicted to hit us can miss by eye-watering margins, simply because the problem is that difficult to solve. (I am again assured that astrophysicists are trying, but the problem is akin to getting a very angry ball of rock to just play nice!)

Clearly, chaos is an important topic in the universe, and to understand the universe better, we require ways to deal with the inherent chaotic nature of these processes. For that, however, we need to take a deeper dive into what chaos means mathematically, which we shall do in the next article.

[…] Last time, we discussed vaguely what is meant by mathematical chaos, and explored some systems that exhibit the properties required to be classified as chaotic. In this article, we will delve deeper into the chaotic realm and look at what exactly must be true for a system to be chaotic, as well as introducing the logistic map as an example of how simple models can sometimes end up being incredibly complicated. […]

LikeLike