Tom talks to Trouw in the Netherlands newspaper about some of his favourite applications of mathematical modelling to a range of sports. The original article is in dutch via the pdf, with a translation copied below.

Who can call themselves the best footballer of all time? It’s a question that can endlessly intrigue sports fans. This also applies to Tom Crawford. One difference: the Brit is an expert in applied mathematics and lectures at the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. Crawford uses mathematical models to find answers to “real-world dilemmas,” as he puts it. “Who is the best athlete, for example? You can measure something like that.”

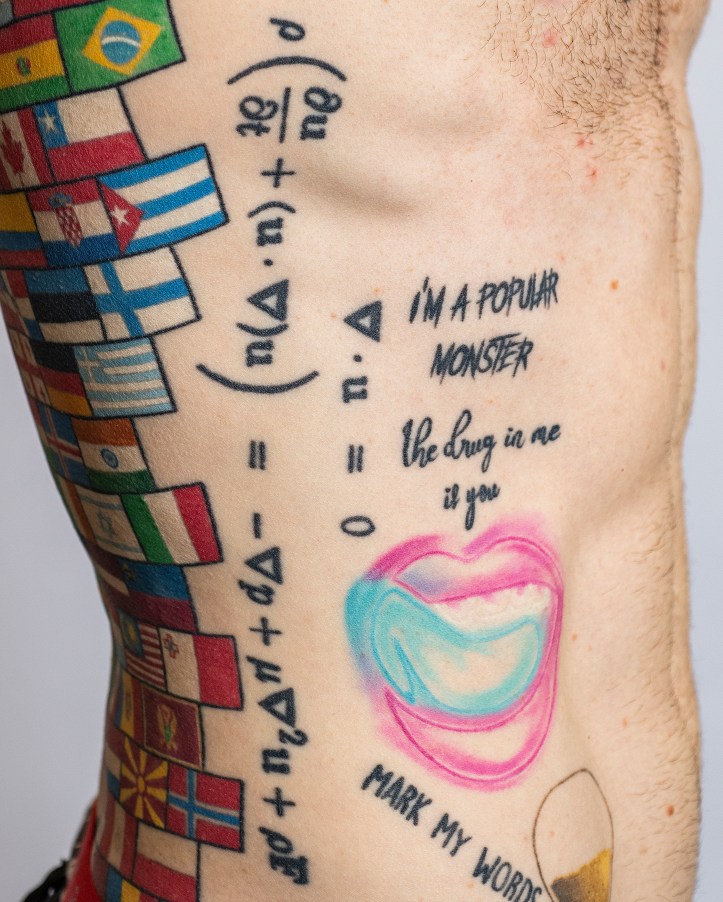

The answer to this question will follow shortly. First, a closer look at Tom Crawford, a rather eccentric scientist. His body boasts countless tattoos, including mathematical formulas, cartoon characters (Spongebob), song lyrics (“the drug in me is you”), and flags of countries he’s visited (68 so far). He doesn’t shy away from stripping down to his underwear during his lessons, to show that math is anything but serious and boring.

With his videos on the YouTube channel “Tom Rocks Maths” (over 236,000 subscribers), he tries to make mathematics appealing to a wide audience. For example: how many ping-pong balls does it take to lift the Titanic from the ocean floor? The answer from Crawford’s calculation: 1.5 billion. “They cost $750 million together,” he says. “Building a new Titanic is cheaper, by the way.”

The Brit is a keen athlete. He enjoys soccer and runs marathons. This led him to wonder how sports can benefit from applied mathematics.

What is your most important discovery?

“The influence of the rotating Earth on rowing. Without a doubt.”

This requires explanation. The Earth rotates on its axis, but humans are too small to feel it. Yet it has consequences. Crawford: “If you hit a golf ball a few hundred meters, the spinning earth will cause it to deviate just a tiny bit. Maybe 0.4 centimetres. In this case, no one will notice that the ball isn’t traveling in a straight line for this reason. The influence of the wind is much greater.”

So what does this observation mean for the athlete?

Research has also been conducted into the effects of the rotating Earth on throwing a cricket ball. The effect is negligible. But here’s the interesting part: rowers move through water, where there’s much more resistance than in the air. If you extend an arm while cycling, you keep going straight. But if you’re in a boat and put an arm in the water, you’ll turn. Rowers have to cover two kilometres in a race. The rotating Earth essentially pushes the boat 40 meters to the side. Rowers keep going straight because they compensate for this deviation, without even realising it. Scientists have calculated that these athletes waste 7.5 to 8 percent of their energy fighting the rotating Earth. That’s a huge amount. In top-level sport, even a 0.1 percent gain is considered groundbreaking.

The question remains: what benefit does this bring to sport?

“That calculation about 7.5 percent energy loss was done with rowers in London. The closer you get to the equator, the less the effect of the rotating Earth, the less energy loss. So, in short: if you want to row world records, you have to do it at the equator.”

Why doesn’t that happen then?

“Yes, interesting question. I’ve presented my findings to rowing clubs, and the funny thing is that the answer is always that it’s much warmer around the equator. That’s annoying for rowers, which negates the advantage due to the tougher conditions.”

Then there should be a perfect spot for world records, somewhere between England and the equator, where it’s not too hot and where the rotating Earth has less influence.

“You know, I’ve been working on this for seven years. I’d really like a professional rower to figure this out. But who can I get?”

Tom Crawford plays football with his team on Sundays. He’s the penalty taker. Until recently, he could say he never misses, but last season, one was saved. And that’s a shame, because he approaches penalty kicks purely mathematically. What’s the perfect penalty? In other words, which shot has the greatest chance of scoring? That’s what he wanted to find out.

Was that the impetus for you, your own football career?

No, I remember seeing data from the German national team. They won more than 80 percent of their penalty shootouts in major tournaments. And England less than 20 percent. You’d think the chance of winning a penalty shootout is 50 percent. People would say it’s a lottery. That’s not true, says the mathematician in me. I thought: imagine if I could whisper something in the ear of the English footballer taking the penalty, what would I say?

The answer to this question requires a complex calculation. A 43-minute explanation by Crawford is available on YouTube. He makes a few assumptions: the goalkeeper stands exactly in the centre of the goal and only moves once the player touches the ball. It takes half a second for the ball to reach the goal line, and during that time, the goalkeeper can stretch out approximately 2.86 meters to the side. According to statistics, there is a 50 percent chance of a goal when the ball is shot within the goalkeeper’s reach. A shot outside that 2.86 meters and inside the goalposts has an 80 percent chance.

There’s always a chance the shooter will take too much risk and hit the crossbar or post. Crawford set out to find the perfect location, the spot with the maximum distance from the crossbar, post, and goalkeeper. Eventually, using mathematical formulas like the Pythagorean theorem, he discovered the perfect penalty: the ball must land in either the top left or top right corner, 65 centimetres below the crossbar and 65 centimetres from the post. Anyone who succeeds has “more than a 99 percent chance” of scoring.

Was the English Football Association interested in your research?

Crawford laughs: “I’ve never spoken to anyone from the association, so I have no idea.”

How can the sport benefit from this?

“I think all the teams in the Premier League now employ data analysts with mathematical skills. There’s been an incredible professionalisation. This also applies to psychology. You can aim every penalty in the perfect spot, but at some point, opponents will notice, of course. Being aware of this is incredibly valuable for footballers. The England players, who are terrible at penalties, need to start with the basics. First, be able to take the perfect penalty, and then practice the mental aspect.”

Crawford explains that he’s currently training for next year’s Brighton Marathon. He’s run five so far, the fastest in 3 hours and 11 minutes. The scientist knows the secrets and pitfalls of the marathon, the brutal battle over 42 kilometres. He also knows the men’s world record by heart: 2 hours and 35 seconds. This leads him to wonder when that magical 2-hour barrier will be broken. And by extension: how much faster can it actually go?

For Crawford, this is a matter of modelling. Using as much data as possible to see when the curve, which is increasingly flattening, will drop below 2 hours. His conclusions: there’s a one-in-ten chance that this will happen sometime in the next five years. And a one-in-a-hundred that it will happen within two years. “My calculations show that 1 hour and 55 minutes will be the absolute limit. I don’t see anyone being faster than that in the future.”

But science always involves nuances. There are exceptional athletes who beat every statistic. Such a person is sprinter Usain Bolt. The curve of fastest times in the 100-meter sprint follows the curve as it should, except that the Jamaican creates a huge downward bend.

This brings Crawford to the so-called Z-factor. For every athlete, it’s possible to calculate how far they deviate from the average, to illustrate how exceptional certain performances are. This way, you can compare a footballer from the Spanish league with a footballer from Brazil. Crawford: “Diego Maradona won the title with Napoli in the 1980s and scored only sixteen times. That doesn’t seem like much, but he did become the top scorer. The Z-factor helps us compare his performance with, for example, Erling Haaland, who scored 36 goals in one season for Manchester City.”

And who wins?

“Haaland’s Z-factor was 2, Maradona’s 2.9.”

Does that also make him the greatest footballer of all time?

“We investigated this about four years ago, specifically looking at victories, goals, and trophies. Cristiano Ronaldo emerged as the winner then. But after that, Lionel Messi won the world title; I wouldn’t rule out that he would win today.” Crawford can’t resolve the eternal dilemma – Ronaldo or Messi.

With the Z-factor, science can also compare the performances of footballers with tennis players and cyclists with swimmers. The main question remains: how extraordinary is someone?

And who is the best?

It’s an Australian cricketer named Don Bradman. He played in the 1930s and 1940s, and his batting average was almost 100. That has never been equaled. His Z-factor is 6.6. Almost no one scores above 3. There are always exceptional athletes who achieve exceptional results. Incidentally, the best team of all time is a basketball team: the Golden State Warriors of 2015-16. Everyone always talks about the Chicago Bulls of the 1990s with Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen, but they still lose out.

What’s your main goal: helping athletes push their limits or making math a more attractive subject?

“The easy answer is: both. A key task for me at the university is increasing public engagement. I make YouTube videos, visit schools, organise events, and give interviews. I love math; it’s the most fun there is. If I tell a group that Ronaldo is the best footballer of all time, I’m immediately met with a million arguments about why that’s not true. But I use math as a weapon. And that’s how I use sports to make my subject more popular. Plenty of people have unpleasant memories of math because they weren’t good at it in school. If I can create positive associations, I will. For example, I’m currently delving into the mathematics of Harry Potter. But of course, I still dream of breaking the world record for rowing across the equator.”