James Somper

As a species, we are obsessed with looking up. We’ve been obsessed with the sky and what lies beyond for as long as we have existed. Incredibly detailed maps of the night sky date back to antiquity, and the ever-fun topic of the small talk of “so what’s your star sign” is a product of the Ancient Greeks, although the Babylonians did it first, just with slightly different names. We are obsessed with space. Simply gaga for it. This has also led to us to examining space in ever-increasing detail, which is absolutely excellent for newspapers, as every so often they get to print headlines that read something along the lines of:

DEATH FROM ABOVE – ASTRONOMER PREDICTS ASTEROID WILL ENTER EARTH’S ORBIT WITHIN DAYS

which gets everyone to buy their paper, only to discover when the big day comes, there’s actually no impact, and the asteroid flies past the Earth, doing no harm at all. It’s weather forecasting all over again!

In fact, it is indeed weather forecasting all over again, as the solar system is another example of a chaotic system, which brings with it all the consequences of chaos that we have become familiar with over the span of the last 3 articles. To explore this specific example in detail, we first must concern ourselves with some mathematical history.

The solar system can be considered a N-body problem, where there are a certain number of bodies (be that planets, spheres, electrons, apples, books) interacting with each other in some way. The most basic chaotic N-body problem is the 3-body problem (ie. N = 3).

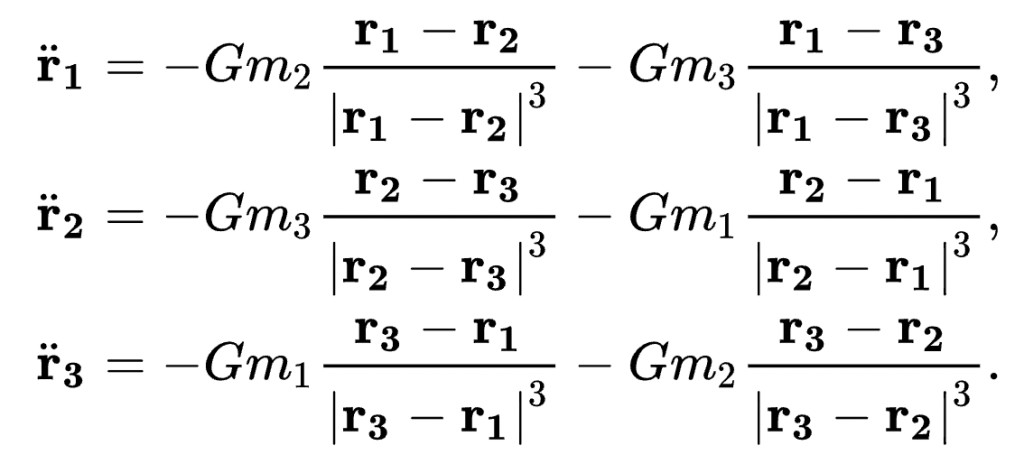

The 3-body problem describes a situation in physics that involves taking the initial momentum of 3 bodies, and according to Newton’s laws of motion and law of gravitation, attempting to solve some equations for their subsequent motion. At first this may seem like an easy enough problem, as we can write down all the equations very simply as:

These equations show that the acceleration of each body (given as rn double dot) is equal to the gravitational force acting on the object due to the other two bodies, divided by the objects mass.

If this system contained only 2 bodies, it is exactly solvable. This means it allows perfect prediction of where the two bodies will be at any point in time, and in fact, one of the cases is what we may have intuitively guessed – the two bodies orbiting around a fixed point. We could, therefore, expect the 3-bodied system to behave similarly, ie. with the 3-bodies orbiting around a fixed point. However, this system has no closed-form solution, which is to say, that unlike the 2-body problem, there is no function that will predict perfectly the position of all three bodies at an arbitrary point in time. Systems of this kind instead exhibit chaos, with very small changes in the initial conditions causing very large changes in the final state of the system. Observing such as system we see the bodies alternating from all condensing to one point, to instead flying apart from one another, almost as though they are slingshotting each other away from a common centre. What’s worse is that the motion is usually non-periodic, presenting another hurdle to predicting the motion of the 3-bodies. Generalising further, N-body problems exhibit the same sort of chaotic behaviour as the 3-body problem.

N-body problems appear all the time in nature. Last time, we discussed the equation that describes the motion of electrons in a helium atom, and how it is inherently chaotic and cannot be solved analytically. This system is almost identical to the 3-body problem discussed above, except the forces are primarily electrostatic, rather than gravitational. In practice, all higher atoms, such as lithium, beryllium, and even the largest element known currently, oganesson (which has 118 electrons) can be considered 4, 5, and 119-body problems (1 more than the number of electrons, as one has to count the nucleus as well).

Another example of a 3, or rather N-body problems, is the solar system, where the Earth, Sun and Moon make up the classical 3-body problem, and the solar system as whole can be considered an N-body problem. This of course means that the solutions are inherently chaotic and thus modelling the solar system must be approached numerically.

Now, for probably the last time in this series, let us remember the tenant of mathematical chaos: a small change in the initial conditions causes a large, unpredictable change in the outcome. Considering this in the context of predicting if an asteroid is going to hit the Earth (and by extension, the path that the asteroid is going to take), if the measurement of the velocity, position, mass, etc. of the asteroid is even slightly off, then this will lead to a massive change in the motion of the asteroid. Even if the change isn’t massive, and leads to just a 1% change in the displacement, given that cosmic measurements are often on the scale of millions of kilometres, even small relative errors are large in absolute terms. Which explains why these asteroids can end up missing by massive margins, as the modelling is incredibly difficult, because the systems are chaotic. In addition to this, even being only 1% out often still isn’t good enough.

However, there are ways to tame chaos. The motion of the Earth, Sun and Moon is well-studied and well-known, as well as predictable. This is due to a simplification of the problem due to the differing masses of the bodies. Instead of the general 3-body problem, we instead consider the restricted 3-body problem, where, in this case, the mass of one of the bodies is taken to be negligible compared to the others. This then means that the gravitational force exerted by it on the two other bodies is effectively zero, and so the problem reduces to the two-body problem, which, as we discussed earlier, is exactly soluble. This is very useful, as it allows us to almost exactly predict the motion of the Earth, the Sun and the Moon, so events such as eclipses can be predicted with almost pinpoint accuracy. This only works, however, because the Sun is much more massive than the Earth (around 333,000 times more massive) and the Earth is more massive than the Moon (around 100 times more massive). It is this difference in masses that allows us to begin to tame the chaos.

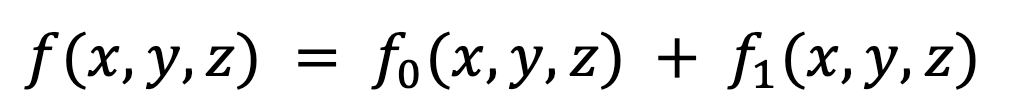

In addition to the method of averaging that was discussed in the last article, there is another tool that exists for those wanting to combat chaos: perturbation theory. This assumes that the effect of the third body, or an external force, or whatever else may change the system from an exactly solvable system to a non-solvable one, can be treated as a small “perturbation” to the overall system. In practice this means the system can be modelled as:

Where f0 is the “unperturbed”, exactly soluble case, and f1 is referred to as the first-order correction to the function. One can, in principle, continually add more and more correction terms to the overall function, which would be called the second, third, fourth, etc. order correction.

In order to solve practical problems in the sciences, perturbation theory is often used to allow progress to be made, using things that we can solve exactly to approximate things that we don’t know exactly. It is a staple technique also used in Quantum Mechanics, an area where equations are very rarely solvable as they exist in their unmodified state.

Overall, we have seen that chaos is all around us. It is in every wave that crashes on the shore; it is manifest in the planets we observe and live our lives on; it is in the weather that we love to complain about; and it lies at the heart of the motion of every atom in our body. Chaos is everywhere, and whilst we cannot exactly solve any of these systems, I hope to have left you with an understanding of what chaos truly means, and how we are sometimes able to tame it and make use of it. We no longer have to be servants of chaos, we can instead make chaos serve us.

[…] Next time, we will explore our final example of chaos in nature, and we will be turning our eyes to the stars – read it here. […]

LikeLike