Joe Leach

Readers who are familiar with secondary school maths and physics (or are fans of Despicable Me) may feel that the answer to this question is obvious: a vector is an arrow between two points in space, or, alternatively, a vector is a quantity with both length and direction (if you know the length of an arrow and which direction it’s pointing in, you know everything there is to know about the arrow). These are both correct. But what if I told you that (x – 3) is a vector? What about sin(x) and cos(x)? Seems weird, right? How can a function be a vector?

Well, it all has to do with the second definition of a vector (a quantity with both length and direction) – if we can find a way to define the “length” of a function, and the “angle” between two functions (which will ultimately give us a direction) then, in a sense, they’d be vectors.

Thinking of the arrow vectors that we’re most familiar with, it turns out that both length and angle are described by one thing – the “dot product”. As a reminder, the dot product is defined as follows for 3-D vectors:

If u and v are vectors and θ is the angle between them, the length of u, which we will denote [u], is found by [u] = √(u . u) (think about Pythagoras theorem), and the angle θ can be found by cos(θ) = (u . v)/([u][v]) where the square brackets denote length as defined earlier (again this can be proved with a bit of trigonometry, just remember the cosine rule).

So, if we can find an equivalent of the dot product for functions, let’s call it * for now, we could define the “length” and “angle” of a function, making it (sort of) a vector. Hello abstraction my old friend…

If we want to define length and angle, we must first understand what we want them to look like, and thus what properties our product, *, should therefore have.

- Firstly, we require symmetry: the angle between u and v should certainly be the same as the angle between v and u. in terms of our “star” product this means:

(u * v) = ( v * u).

- Secondly, the length of a vector should be positive (have you ever seen anything that’s -3 metres long?) and only be 0 if the vector itself is 0. This means we need the following property:

(u * u) > 0 if u is not 0, and (u * u) = 0 if u = 0.

(Aside: can you see why this is true for our normal dot product?)

- The final condition is a little more subtle (we’ll see why it’s important later), but essentially it says if we have 3 vectors u , w and v and some numbers, say, a and b, then:

(au + bw) * v = a(u * v) + b(w * v )

Let’s check to make sure this holds for the standard dot product introduced above:

So, why do we need this property? The above equation describes a type of linearity; a very useful concept for mathematicians because we can prove a lot about things that satisfy this condition. We would also, therefore, like to preserve this so that some of the useful things we know about arrow vectors may be applied to our new “function vectors”. This is once again one of the core concepts of abstraction.

Together these 3 properties turn out to be all we need for a consistent idea of length and angle, at least for this application.

Now, if some of the maths I’ve talked about went over your head, don’t worry, the essence of it is this:

- There is something called the dot product for arrow (normal) vectors that determines length and direction.

- The dot product has three important qualities that, if we can reproduce for function vectors, we can then define their “length” and their “direction”.

So now the big question: does such an operator exist for functions? I’m sure you’ve guessed by now that I wouldn’t waste so much time writing about it if such a thing didn’t exist, and you’d be right. In fact, there are many (this may seem concerning but we simply use whichever notion of length and distance is most useful to us for a given application). The below example using integration is particularly useful as it means that we can use trigonometric functions like sine and cosine as a “basis”, an idea that we’ll discuss further in a moment.

If you know how to compute integrals then as an exercise try checking that the 3 properties from earlier all hold for the new operator * defined by the given integral. Otherwise, just note that with this operator, we can now consider functions to be vectors, and we are done.

But, frankly, why should you care? It’s cool that we can create something for functions that satisfies some of the same properties as for vectors, but isn’t it a little arbitrary? Haven’t we just made up a definition of distance and angle and shown we can satisfy it? Well, at first this may seem so; that it’s just a fun mathematical oddity, but if it were just that, I wouldn’t be talking about it now. Let’s take this just a little further to see the magic unfold.

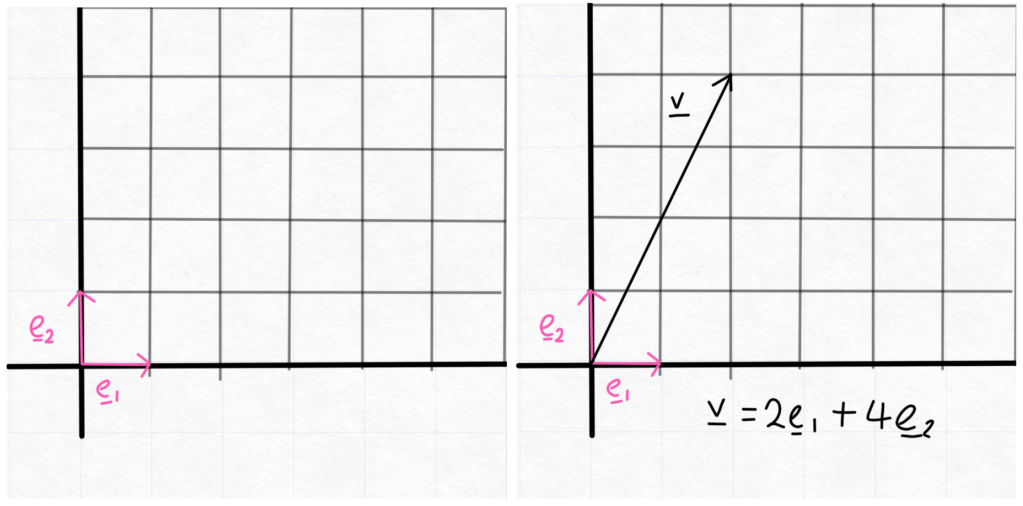

We begin by defining possibly the most important thing in linear algebra: a “basis”. Returning to our 2-D arrow vectors, the (canonical) basis is simply the vectors:

Or in other words, the vectors of length 1 in the x and y directions respectively. These are a basis because every 2-D vector can be uniquely represented as a linear (there it is again) combination of the 2 basis vectors. Or in other words, any point in the 2D plane is just some amount of the first one, plus some amount of the second one.

We note also that these basis vectors are perpendicular to each other (check this by using the dot product angle formula defined earlier), and so that brings a natural question: with our new definitions of length and angle, can we find a basis for function vectors (pieces that all other functions can be built from) where the basis vectors are of “length” 1, and are “perpendicular” to each other? The answer to this question is a resounding sort of…

With * as before we can find a basis for some functions, but we only have information about how the function behaves from -π to π (because sin and cosine are periodic – they repeat every 2π), so we’re going to need the function to repeat its behaviour between -π and π over and over again. (Note that our basis vectors will need to act like this too – what functions might work like this?).

Mathematicians would say that the function needs to be 2π-periodic. This might seem to be a big problem, but in reality, if we’re interested in how a function acts in a certain region, we can often just scale a function so the region we’re interested in is between – π and π so this isn’t an issue.

So, can we define any 2π-periodic function in terms of a basis? Well, nearly… but instead of having two basis vectors as with the x-y plane, we now have an infinite number of basis vectors. (We can also only represent functions that are suitably “smooth” but this is pretty much all “normal” functions, so this is less of an issue).

Using our formula from above for *, we see that for all positive integers m, sin(mx) is a basis vector of “length” 1 and for all non-negative (so positive and 0) integers n, cos(nx) is a basis vector of “length” 1. By computing the products we can also see that every basis vector is “perpendicular” to all the others. (Challenge: verify these properties using the formula for *.)

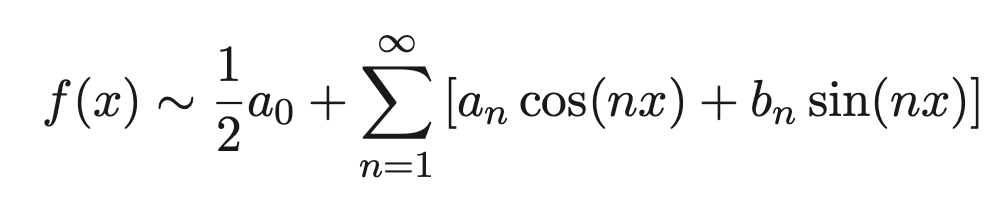

So, any function from -π to π can be represented as a linear combination of sines and cosines. And here is the – rather complicated looking – mathematical formula:

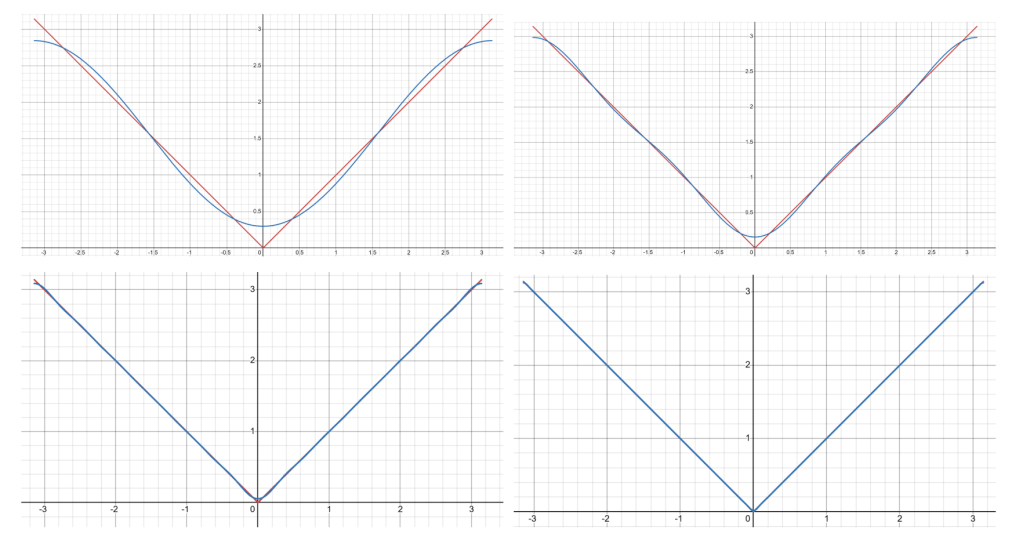

Not only that, but we can even work out the coefficients of each basis “vector” (the an and bn above) for a given function using an area of maths called ‘Fourier Series’. Here are some plots showing how adding more and more sines and cosines leads to better and better approximations to a function. (There’s also a link to a Desmos file here so you can play with them to your heart’s desire.)

So why is this useful? Well, there are many natural scenarios in which these infinite sums of sines and cosines (known as Fourier Series) appear, and they allow us to solve complicated second order partial differential equations. Consider the following example: when we heat up one side of a room, eventually the heat will move around the room and even out, so that the room is all the same temperature. The equations that model the way that heat moves in an environment like this are solved with these series of sines and cosines. So too are the equations that model waves. And pretty much everything in our universe is a wave.

Finally, let’s return to our central theme of abstraction, and think about what this example can teach us about the nature of maths? To me, this is a beautiful exemplification of how abstraction can bridge the gap between different areas of maths. You start trying to solve physical problems in differential equations – such as the dissipation of heat in a room – but the idea of functions as vectors, and sines and cosines as a basis, something that should, by all rights, be an interesting but purely mathematical concept, arises as the solution to your real-world problem. In school, we are often given the impression that maths is a collection of disparate topics each with their own tools and ideas. But, as you dig deeper, you start to uncover bridges between these topics, and the things you thought were little fun coincidences turn out to be fundamental and important connections between these topics. You feel that you’re getting a glimpse at the deep structure of mathematics. Beauty may be in the eye of the beholder, but if there is beauty in maths; to me, at least, it lies within these revelations.

The 4th – and final – article in the series will be available soon.

Article 1: The Path Towards Higher Mathematics is Guided by Abstraction

Article 2: Abstraction and Graph Theory with Euler

[…] Read the next article in the series here. […]

LikeLike

[…] Article 1: The Path Towards Higher Mathematics Is Guided By AbstractionArticle 2: Abstraction and Graph Theory with EulerArticle 3: What is a vector ‘really’? […]

LikeLike