Joe Leach

Being the fourth, and final article in the series, it’s time for the good stuff. Let’s use abstraction to generalise numbers themselves…

As we’ve seen in the first three articles, in order to ‘abstract’ something, we’ve first got to work out what the key features are. Despite our familiarity with numbers, it can be hard to pin down what makes them special and useful in a mathematical sense. However, I hope we can agree that the existence of “+” is pretty important. In fact, this is an example of what is called a binary operation – a function that takes in two elements from a set (in this case numbers) and outputs another element (number) in that set, i.e. if we input 3 and 4 to our plus function the output is 3 + 4 =7.

Okay, but + has more features than that. Associativity and commutativity (adding numbers in any order we will always get the same answer) are certainly important, so we may want to include them in our generalisation. But what about the numbers themselves? Well, if we have + we should certainly have 0. It holds a special place within the numbers with many useful properties (as we’ll soon see).

Lastly, I’m going to ask for something that may seem a little odd: the negative numbers. Why are these so important? Well, they are the inverses of the positive numbers, x + (-x) = (-x) + x = 0, which gives us something known as the cancellation property: if x + 3 = y + 3 then x=y. This seems obvious, but remember that we only have the operation + so if we want to subtract we have to add a negative number. There are also some situations where the cancellation property doesn’t hold, for example with matrices we could have AB = AC with B and C not equal if A isn’t invertible (i.e. it has a zero determinant). Since we do want this property to hold for our generalised numbers we will need inverses.

With all that in hand, let’s define a group: a group (G, *) is a set G, with binary operation * on G, that satisfies the following conditions:

- There is an element e in G such that for all elements g in g e * g = g * e = g

(for the “set” of numbers with the “binary operation” +, e is 0 since x + 0 = 0 + x = x) - * is associative, meaning (g * h) * l = g * (h * l)

- For all elements g in G there exists h in G such that g * h = h * g = e

(these are our inverses, for the set of numbers with +, h is -g as g + (-g) = (-g) + g = 0)

Now, those of you who that have been paying particularly close attention will see a notable omission – we haven’t yet said anything about commutativity. This motivates another definition: a group is abelian if the binary operation * is commutative, i.e. g * h = h * g.

Why don’t we include it in the original definition? Well, it turns out we can do a lot of interesting maths without the need for commutativity, and there are systems which are groups but aren’t abelian. So, in the interests of generality, we consider commutativity a “bonus feature” that affords us more tools. A final technical point worth mentioning before we move on to examples is that a group may be finite or infinite in size.

For our first example, let’s leave numbers behind and think about a square and its symmetries. You may recall from the first article that there are eight in total: four rotational symmetries and four reflectional symmetries (including doing nothing, which is our zero equivalent, “e” from before). We can think of these to be the elements of a set where the operation is composition of symmetries (doing one action then the other). For example, rotation by 90 degrees * rotation by 180 degrees = rotation by 270 degrees.

Take a moment to verify that this satisfies the 3 group axioms above. Is it abelian? Perhaps the least obvious part of the proof is that any composition of two symmetries is itself a symmetry. Although intuitively, this should make sense, since a symmetry is an operation that doesn’t change how the shape “looks”. Doing two operations that don’t change how a shape “looks” therefore also doesn’t change how it looks.

A further interesting property of groups, is that they can contain smaller groups within them referred to as “subgroups”. With our symmetry example, notice that “adding” any two rotations will always give us a rotation, and so the set of rotations (counting doing nothing as a rotation of 0 degrees) is a subgroup of our symmetry group. Now this “rotation group” is abelian. It doesn’t matter which order you rotate things in, you’ll always get the same result, a rotation by an angle equal to the total of the sum of the angles of the rotations. The other thing to be noted is that the size of the rotation group, four elements, is a factor of the size of the group of all symmetries (eight).

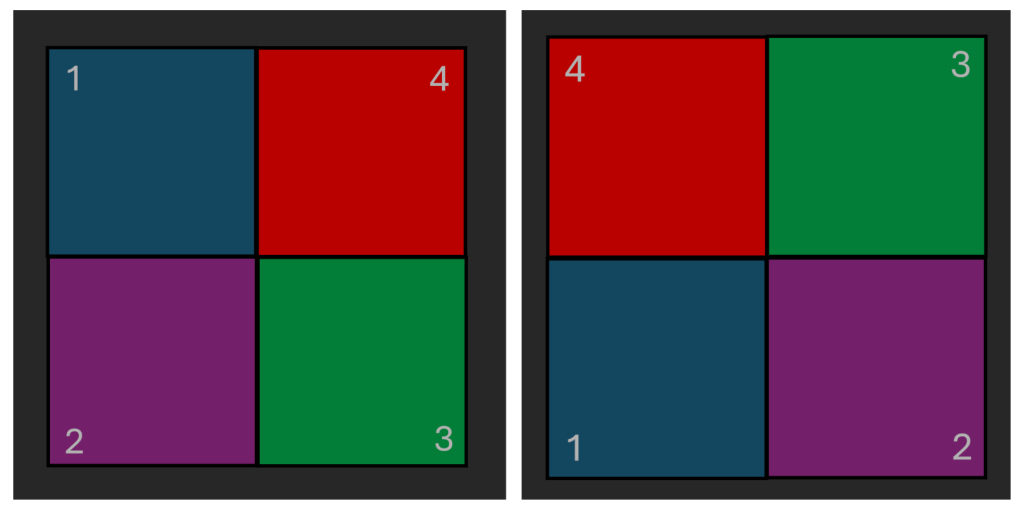

Perhaps surprisingly, this is true in general. Lagrange’s Theorem states that if H is a subgroup of G, then the number of elements in H divides the number of elements in G. I’m not going to prove this here, though we will study the implications in a puzzle sheet later if you’re interested. An interesting question to ask is whether we can we also go in the other direction? Namely, is there a group that has our larger square symmetry group as a subgroup? Well, if we label each corner of the square anti-clockwise from the top left corner 1, 2, 3, 4 respectively, then all our symmetries are represented by some rearrangement of these numbers. For example, a rotation of 90 degrees gives 4, 1, 2, 3 as seen below.

With this labelling procedure, the symmetries of a square are actually just a subgroup of all the rearrangements of the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, which are known as permutations. It’s important to note that whilst every symmetry is a permutation, not every permutation is a symmetry. For our square example, no rotation or reflection can put 1 and 3 next to each other, but 1, 3, 2, 4 is a perfectly fine permutation.

So, returning now to numbers, what can we discover about permutations using intuition from numbers? Well, one of the most mathematically important features of positive integers is their unique prime factorisation, so what if there were an equivalent within permutations? It turns out there is, but to find these ‘permutation-primes’ we’ll have to take a little detour through something called cycles.

Okay, what is a cycle? In this context, a cycle is a permutation where some numbers do not change and all the others can be followed in a chain from the first number back to itself, e.g. “1 goes to 3, 3 goes to 5, 5 goes to 7, 7 goes to 1 and 2, 4, 6 are all fixed in place” is a cycle belonging to the group of permutations of 7 elements. This would be denoted (1357) writing the cycle in order and ignoring fixed numbers. [Note that (3571) is exactly the same thing, it doesn’t matter which element of the cycle is listed first as long as the order remains unchanged.]

Usually if there are k numbers in the chain (or cycle), it is referred to as a k-cycle. Why are these cycles important? Well, these will form our primes for permutations. Every permutation has a unique factorisation into cycles. To see this, take any ordering of the first 7 numbers, say 3, 1, 2, 7, 5, 4, 6, now track the chain with 1 in, (123) since 1 is now in the second position, 2 in the third position, and 3 in the first position. Next, follow an element not in that list, say 4. This is now in position 6, whilst 6 is in position 7, and 7 is in position 4. As a permutation this is (4,6,7). Finally, 5 hasn’t moved so we say it is fixed. Therefore, we have 3, 1, 2, 7, 5, 4, 6 = (123)(467) using the cycle notation.

We can follow this method in general, noting that by picking 1 we uniquely determine the cycle that contains one, and then by picking 4 the other cycle is also uniquely determined, so this is also the only way to decompose it into cycles. Now, it must be noted that not every group has unique prime factorisation, it’s a somewhat special property that permutations have, but still, we see reflections of our understanding of numbers in our study of permutations.

Group Theory is an incredibly deep area of maths that we have just scratched the surface of today. The use of abstraction allows us to study systems similar to numbers, sometimes to gain intuition for these systems from numbers, but the incredible thing is that since we can go both ways, group theory also has significant applications to numbers themselves. The impossibility of a quintic formula (the explicit solution to a polynomial equation of order 5) was proven using groups. In number theory we find that primes have special properties in certain types of group (more on this in the puzzle sheet), which means group theory offers a useful lens for studying primes. And as we’ve seen in this article, we’ve rediscovered the fundamental theorem of arithmetic using permutations.

Abstracting the concept of numbers helps us to study the very numbers we derived groups from in the first place. It may at first seem circular, but there are certain finite groups of numbers (think of remainders), that are most naturally studied in the generality of group theory. Our discussion today provided a new context to think about numbers through permutation cycles, which if taken further could in fact provide a new way to understand numbers. Just like in life; in maths, sometimes all you need is a new perspective.

Article 1: The Path Towards Higher Mathematics Is Guided By Abstraction

Article 2: Abstraction and Graph Theory with Euler

Article 3: What is a vector ‘really’?