Chenying Liu

In part 1 we learned Tom’s strategy for trying to catch Jerry, so now let’s here how the mouse plans to escape…

Jerry’s Strategy

Little Jerry, knowing nothing about Tom’s plan, also shows superior intelligence. He decides no matter where Tom is he will run in the direction perpendicular to the radius he is currently on, in the direction opposite to Tom’s current location. Let’s look at an example in the diagram below. Jerry’s location is given by M1 and Tom’s by C1. According to Jerry’s strategy, he will run to the upper part of the circle (away from Tom) and make his path perpendicular to OM1 (the radius Jerry started on).

After running for time period t1, Jerry arrives at the new position M2. As long as M2 hasn’t reached the edge of the stadium, Tom will not have been able to catch Jerry. Here’s why…

As Jerry’s path M1M2 is perpendicular to OM1 and away from Tom’s initial position C1, angle C1M1M2 is obtuse (greater than 90 degrees). We know that the shortest path for Tom to reach Jerry is the straight line C1M2. According to the Cosine Law and the fact that cos(C1M1M2) ≤ 0 (since cos is negative for angles between 90 and 180 degrees), we have:

Thus, it’s clear that C1M2 > M1M2. Because both Tom and Jerry move at the same speed, Tom cannot cover a longer distance (C1M2) than Jerry (M1M2) during the same time period.

So what happens next? When Jerry is at M2, Tom will be at some point C2, which is between C1 and M2. What should Jerry do? Again, according to his strategy, he will run away from Tom making his path perpendicular to OM2.

After time period t2, Jerry is at some new point M3. Once again, the quickest way for Tom to reach M3 is to go in a straight line to that point. However, because of the same reason we demonstrated above, we have C2M3 > M2M3 and so Tom fails to catch Jerry again. Jerry can now continue to move in this way for as many steps as he wishes to continue to stay out of reach of Tom… However, the condition for this to succeed is that Jerry should never reach the edge of the stadium at any step or Tom may catch him. So, the question now becomes how can Jerry meet this condition?

After thinking for a while, Jerry comes up with the following idea. If we take t to be a very small time period, then Jerry chooses t1 = Δt, t2 = Δt/2, t3 = Δt/3, … , tn-1 = Δt/(n-1), tn = Δt/n, … and so on for each of his steps. We now want to know here Jerry will be after n such steps, so let’s calculate his distance to the centre. Suppose that initially Jerry is at point M1 and call the distance from the centre O to M1, OM1 = r0.

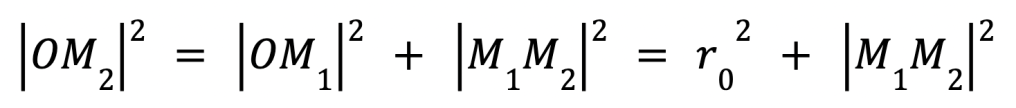

At Step 2 in Jerry’s strategy, Jerry is at point M2 and so to calculate his distance from the centre we need to calculate the length of OM2. We already know that M1M2 is perpendicular to OM1 so the square length of OM2 can be obtained by Pythagoras’ theorem:

In the third step, Jerry is at point M3. We know the length of OM2 from the last step and M2M3 is perpendicular to OM2. Again using Pythagoras’ theorem, (OM3)2 = (OM2)2 + (M2M3)2. Substituting the value of OM2 from above, we have the square length of OM3:

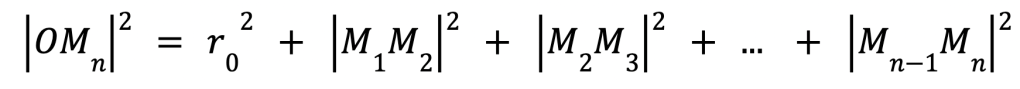

Can you spot the pattern? If we continue in the same way for each of the steps, the square length of (OMn)2 at Step n will be (OMn)2 = (OMn-1)2 + (Mn-1Mn)2 and substituting in the formula from the earlier steps we get:

We now have a formula for Jerry’s distance from the centre at step n in terms of the distances M1M2, M2M3, … , and Mn-1Mn. If we consider Jerry’s speed v and his running time for each step, we can also compute these distances using speed = distance/time. Recall that Jerry has already chosen the time for each step as:

Step 1: t1 = Δt; Step 2: t2 = Δt/2; Step 3: t3 = Δt/3; … ; Step (n-1): tn-1 = Δt/(n-1); Step n: tn = Δt/n, where Δt is some small time period which we will worry about later.

Then the formula distance = speed x time gives

Substituting these values into the equation for OMn, we get

by factoring out the v and t terms.

We could try to calculate a formula for the sum 1 + 1/22 + 1/32 + … + 1/(n – 1)2 but we can save ourselves considerable work by instead estimating the value.

For each term in the sum, we use an inequality to set up the estimation. Now, for any fraction, keeping the numerator unchanged and decreasing the denominator will make the number smaller. For instance, 1/22 = 1/(2*2) < 1/(1*2). Similarly, we can have 1/(n-1)2 = 1/(n-1)(n-1) < 1/(n-2)(n-1).

Thus, we can estimate the value of 1 + 1/22 + 1/32 + … + 1/(n – 1)2 by

The new sum is ‘better’ than the previous one because it can be calculated much more easily. We first note that the fraction 1/(n-2)(n-1) can be decomposed into: 1/(n-2)(n-1) = 1/(n-2) – 1/(n-1).

Replacing each component of the sum in a similar way, we have:

with all other terms cancelling out. Comparing the two sums, we obtain the estimation as

Therefore we have

If we call the radius of the stadium r, then to avoid reaching the edge, Jerry always requires (OMn)2 < r2 no matter how large n is (ie. how many steps forward in time he goes). Looking back at the expression for (OMn)2 above, we have 3 variables r0, v, and t. Jerry’s initial distance to the centre, r0, is randomly decided. His speed, v, is a fixed value which is the same as Tom’s and decided by the referee of the Endgame. Only the small time period Δt can be controlled by Jerry by how often he changes his direction. This is in fact the key point: can we choose a small enough Δt to make r02 + 2v2Δt2 < r2? If so, then Jerry’s distance from the centre at step n will always be less than the radius of the stadium and he will never be caught.

Fortunately, we can just rearrange the expression above to get

and then Jerry will never hit the edge of the stadium. Jerry is going to make a successful escape!

There is one final question for us to consider: for how long will Jerry be running? Whilst we have shown that it is possible for him to remain ahead of Tom and away from the edge of the stadium, we need to check for how long he is able to use this strategy. Let’s do another (final) calculation.

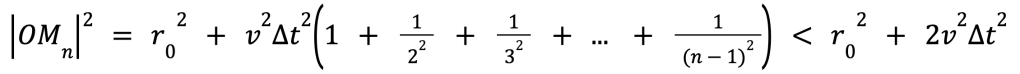

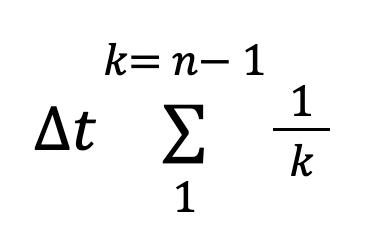

In Step 1, Jerry has chosen time t1 to be Δt, a short time period meeting the inequality above. In Step 2, Jerry will use time t2 which equals to Δt/2. Thus the total time he uses after Step 2 is t1 + t2 = Δt + t2. The time period he spends on Step 3 is t3 = Δt/3 and the total time adds up to t1 + t2 + t3 = Δt + t2 + t3 etc.

Therefore, the whole time t after Step n is just equal to the total time of each step added together, and so is given by:

t = t1 + t2 + t3 + … + tn-1 = Δt + Δt/2 + Δt/3 + … + Δt/(n – 1)

or more succintly

If you’ve heard of the famous harmonic series, you’ll know this is a divergent infinite series. Thus, in our sum, as n approaches infinity, the total will also tend to infinity. And although Δt can be extremely small, it remains non-zero and thus, multiplying the sum by Δt also gives infinity, which means the running time for Jerry can be extended indefinitely!

So what does this mean for the rules of our Endgame? Well, first we might want to set a time limit or it seems it may never end. But, provided he follows the strategy set out in this article, Jerry will always remain out of Tom’s grasp and be crowned the champion! Some things never change…

[…] In the meantime, let’s take a look at Jerry. What will our little Mouse do? Does he have any winning strategy to defeat his arch nemesis? See if you can work it out and then check back to see the answer in part 2! […]

LikeLike