Aryaman Gupta

The decidability problem is a question with a very strange result as far as mathematical results go, simply because of how unusually sobering it is. The problem, simply, is this — is there a ‘mechanical procedure’ (such as a computer program) that could prove any mathematical problem, simply by encoding it in an appropriate way? The result, perhaps surprisingly, is that there is no such procedure. Although this question might seem highly abstract, attempts to tackle the problem led to the development of mathematical models which would eventually facilitate the creation of computers.

The models in question are Turing machines; rather nifty mathematical constructions that allow for notions as seemingly vague as ‘computer programs’ and ‘mathematical problems’ to be expressed in a manner concrete enough to actually prove anything about them. Intuitively, these ‘machines’ (really just abstract mathematical objects) represent a read-write device which works on a magnetic tape (really just a series of binary digits extending infinitely in both directions), on which each ‘space’ is either ‘magnetized’ (i.e. a binary digit 1) or ‘de-magnetised’ (i.e. a binary digit 0). The read-write device itself can move the tape one space either to the left or right at a time. When the device is reading a space, it carries out a single numbered instruction, which tell it three things:

- Whether to change the digit it is currently reading (depending on whether it is presently reading 1 or 0)

- The number of the instruction to execute next

- Which direction the reader should move the tape (or if it should stop)

Once the ‘machine’ has been fed an initial ‘tape’ (represented by a single binary number, where the 1s are the magnetized spots and the 0s the unmagnetised ones), it keeps on executing the instructions as it goes along, either going on infinitely, or stopping after a certain finite number of steps.

Crucially, there are rather clever (albeit messy) ways in which each instruction can be encoded as a single number. This is achieved by ‘encoding’ each step’s three bits of information into one number, and then stringing these individual ‘step codes’ of each numbered step all together. Then, by simply taking the number obtained by chaining together all the instructions in their respective order, an entire Turing machine can be represented by a single number! [However, this doesn’t mean that all numbers encode working Turing machines. Indeed, most don’t.]

Furthermore, any mathematical problem (as is especially evident when natural numbers are involved) could be framed in terms of Turing machines. Consider, for example, the infamous Goldbach conjecture — according to which any even number can be expresses as a sum of two primes. Let us consider, then, a Turing machine that takes in an even number n as its input, and checks if it can be expressed as a sum of two primes; checking if the next even number can be split into primes, and so on, stopping only when it finds an even number that cannot be split in this way. If we had a Turing machine — and thus a computer program — that could decide whether this ‘Goldbach’ Turing machine could stop, it would solve this conjecture, since we can deduce from its halting or not whether the conjecture is true. If it halted at some number, that would mean the number it stopped at can’t be spit into two primes, proving the conjecture false – but if it doesn’t, that means the conjecture is true after all!

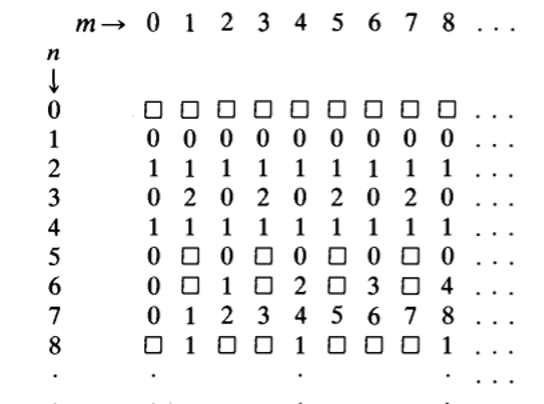

However, as we shall prove, no such machine exists. To see why, we assume such a machine does exist; proving eventually that this leads to a contradiction. We begin by taking a table T(n,m) whose entries represent the values of every Turing machine with instruction number n, and every input m (where squares represent Turing machines that either come across a faulty instruction or do not stop):

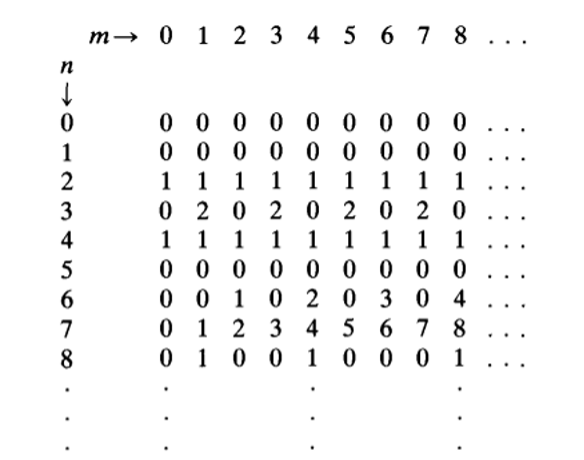

Now, we define another Turing machine, H(n,m), whose value is 1 if T(n,m) gives a result, and 0 if it doesn’t (i.e. when entry (n,m) in the table above is a square). Then, we take a new table by multiplying every entry T(n,m) with H(n,m):

This new table contains all sequences of numbers that a Turing machine can generate (known as computable numbers) — the 0s caused by multiplying by H(n,m) are merely additions, they do not alter any of the computable numbers that actually appear in the table.

Now, at last, consider the machine for a sequence which generates for each natural number n, T(n,m) × H(n,m) + 1. Clearly, since each of these numbers is generated by a Turing machine, the resulting sequence must be a computable number. Thus, as we said above, it should appear somewhere in the previous table. Yet it cannot — for it differs from the first list of numbers by the first entry, the second list by the second entry, and so on. Thus, we reach a contradiction, and there is no ‘mechanical procedure’ (as formalized by a Turing machine) that can decide if any Turing machine stops, and thus no machine that could solve all of our mathematical problems by simply feeding them in. That is to say, the decidability problem cannot be solved.

Undoubtedly, this is very good news for mathematicians afraid of being made redundant by automation. However, beyond that, it also poses very deep philosophical questions regarding the nature of human intelligence, and whether or not there is something ‘special’ about it that no computer could replicate. Since any given Turing machine can, theoretically, be checked to see if it runs indefinitely by a human (with them tediously checking step by step in a very slow and painful process!), this result would seem to almost suggest that there is something unique in the way that our brains work such that we can do what these Turing machines cannot. Furthermore, this also suggests that there is a certain class of mathematical results that only humans can solve — a class which, rather unnervingly (depending on one’s views on the philosophy of mathematics), must thus in some sense be ‘dependent’ on the way our brain works…

This was the second article in a three part series introducing the Philosophy of Mathematics. The last part will explore a closely related problem – that of the failure of logicism, and its inability to provide an absolutely objective, ‘pure’ foundation to mathematics. See you there!

Article 1: An Introduction to Maths and Philosophy – Platonism, Formalism and Intuitionism

Article 3: Mathematical Philosophy: Russell, Godel and Incompleteness

[…] Article 2: Mathematical Philosophy: The Decidability Problem […]

LikeLike

[…] Article 2: Mathematical Philosophy: The Decidability Problem […]

LikeLike