Yu Xiao

Imagine finding this treasure map at an uninhabited island during your journey around the world. The ship denotes our current location, and the treasure is at the centre of the map, buried at the bottom of the sea. Some distances are shown on the map, but we don’t know how far we are from the treasure. If we go too far, it seems that we may encounter some Cthulhu-like creature, so it’s important to figure out where we should stop to look for the treasure. To do the calculations, let’s turn the map into a geometric shape, as shown below.

After staring at the map for a while it becomes apparent that as mere sailors we are not very good at maths, and get bored quickly. The youngest sailor Jack starts to spin his pencil in his fingers, and attracted by his skills, most of us start to spin pencils ourselves – some with more success than others. After a few failed attempts, you ask Jack to teach us the secret to his skill. Jack answers, “You just need to find the balance point of the pencil!”

But what exactly is a balance point? You can think about it as cutting a pencil into two pieces which have the same weight. The point where you make the cut is the balance point. It’s not only pencils that have this property – every object will in fact have a balance point. If we hang an object freely at this point, the object will stay balanced and will not rotate. For this reason the balance point of an object is also known as the gravity centre.

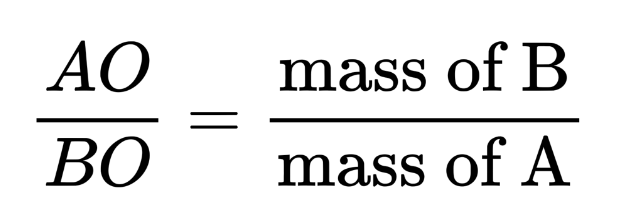

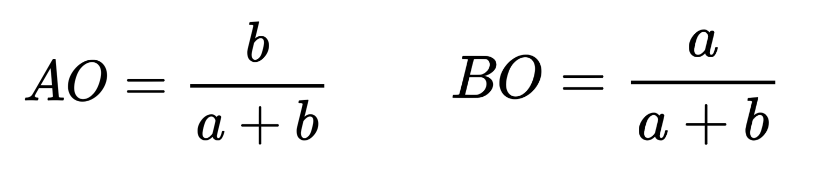

So to excel at spinning pencils, we want to find the balance point of a pencil quickly. Fortunately we can do this just by remembering one important formula. As shown in Figure 4 below, suppose the pencil is a line segment AB of length 1, with masses only at point A and B. Denote O to be the gravity centre of A and B. If point A has mass a and point B has mass b, then the gravity centre O of the two points should be at a position that satisfies:

Since AB = 1, we have the following results:

For example, if both A and B have the mass 1 (a = b = 1), then O is at the midpoint of AB (AO = BO), as shown in Figure 5 below. If a = 1 and b = 2, then AO/BO = 2 and AO = 2/3, BO = 1/3. We can think of the line segment AB as a scale or a seesaw. In order to balance the scale, we want to put a heavier weight closer to the centre, and a lighter weight farther from the centre.

Lemma 1 tells us the gravity centre when we have two points, but what if we have three points? Let us consider this situation as shown in Figure 6: we have three points A, B, and C, each with mass a, b, and c respectively. Denote D to be the gravity centre of points A and B. By Lemma 1, we know AD/BD = b/a.

We can think of A and B as one object, called S, as shown in Figure 7. The object S has mass a+b and gravity centre D. Now, let’s focus on the gravity centre of point C and object S. This is equivalent to the gravity centre of point C (mass c) and point D (mass a+b). Let’s say the gravity centre is O. We come back to the question of finding the gravity centre of two points, so we can apply Lemma 1:

where O is the gravity centre of point C and object S, and so is also the gravity centre of the three points A, B, and C.

If we want to find the gravity centre of even more points, we can represent each pair of points by their gravity centre, whose mass is the sum of the two masses. Combining the points and applying Lemma 1 repeatedly, we can find the gravity centre of the whole system. For example, in the square of side length 1 below, the four vertices A, B, C, D each have mass 1. Points A and B are equivalent to the midpoint E (mass 2). Points C and D are equivalent to the midpoint F (mass 2). Therefore, the gravity centre of E and F is the midpoint O, which is also the gravity centre of the whole square.

Wait. I feel like we’ve forgotten something… The treasure map! Let’s go back to the original problem. Given the lengths of some line segments, how do we find the length of DO?

Points A, B, C are just normal points now, without any masses, but we can assign them masses according to our preference. If A, B, and C have masses such that O is the gravity centre, then we can apply Lemma 1 in reverse to find the ratio of the lengths.

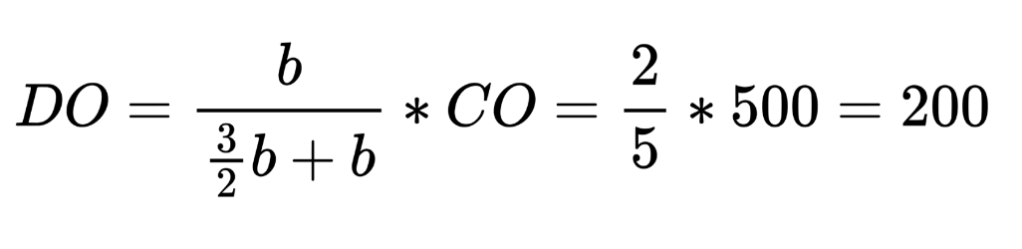

Suppose A, B, C have masses a, b, c respectively, then we know CO/DO and so can rearrange to get the answer:

To recap, we start by considering A and B as one object. In order for O to be the gravity centre of A, B, and C, then D should be the gravity centre of A and B. From the map, we know AD/BD = 200/300 = 2/3. By Lemma 1, we have the ratio of masses b/a = AD/BD = 2/3. Similarly, we think of B and C as one object, and in order for O to be the gravity centre of the three points, E should be the gravity centre of B and C. Lemma 1 gives CE/BE = 400/400 = 1, so b/c = CE/BE = 1.

Finally, we can express a and c with b via a = 3/2*b and c = b. Substituting these expressions back into the formula above gives:

And we have the final answer to our original question! Sail towards the Cthulhu-like creature for 20m and then stop. This is the location of the treasure.

For sailors, finding the treasure is likely more than satisfactory, but the idea of gravity centres can be applied in many other maths problems as well. Given a geometric shape, if we can assign masses to some points so that one important point of the shape becomes the gravity centre, then we can use the ratio of masses and Lemma 1 to find the ratio of the lengths. One specific example is to prove the Ceva’s Theorem.

Back on the ship, we could tell the other sailors currently absorbed with spinning pencils that we have figured out the distance between our current position and the treasure, but maybe its better if we only tell them tell them the answer if they agree to give us 80% of the treasure. Who said maths can’t make you rich?