A huge congratulations to Thomas Shakespeare for their essay titled ‘Rad Math: Exploring Skateboarding Kinematics, World Records and the Intermediate Axis Theorem‘ which has been awarded first prize in the student (under-18) category for the 2024 Tom Rocks Maths Essay Competition.

“Everything a mathematical communication essay should be. Based on an original topic that piques the readers interest; conversational with just the right balance of humour and substance; and mathematics that starts with the familiar (SUVAT equations) and ends with the complex (Intermediate Axis Theorem). Overall, an excellent example of a student with a keen interest in, and aptitude for, mathematics, that was a pleasure to read.”

Thomas’s essay will be published on the university website, and they will receive a cash prize of £100. Here is the essay in full – enjoy!

Rad Math: Exploring Skateboarding Kinematics, World Records and the Intermediate Axis Theorem

Preface:

Understanding the mathematical notation used in this essay is useful for following the more complicated analysis. Here is a brief list of the symbols employed and their meanings:

∴ (therefore): This symbol signifies a logical conclusion or deduction. For example:

2 + 𝑥 = 4 , ∴ 𝑥 = 2

⇒ (implies): This symbol is used to denote implication, indicating that one statement leads to another. For example: 𝑥 = 2 ⇒ 𝑥2 = 4

∵ (because): This symbol shows causation or justification. It is used to show that a statement holds true because of another. For example:

π𝑟2 = 𝐴𝑟𝑒𝑎 ∵ 𝐼𝑡 𝑖𝑠 𝑎 𝑐𝑖𝑟𝑐𝑙𝑒

Additionally, I believe it’s easier to understand and engage with videos on top of diagrams and images. The PDF format does not support GIFs, however I have provided a separate document with all images as GIFs here. (These have been included below where possible).

Introduction:

Everyone has seen skateboarders tearing up the concrete, seemingly breaking the laws of physics with their gravity-defying stunts. But have you ever wondered how they actually do it? How can someone leap onto a plank of wood and jump over obstacles? After all, the board isn’t even attached to their feet. It turns out the answer lies not just in skill, but in mathematics. We will begin by exploring the basics, jumping and flip tricks. Then we’ll go to the skatepark and tackle the ramps. Finally, we’ll look at some of the hardest tricks in the book and how mathematics makes them possible. So get on your knee pads and helmet, because we are going to jump into the world of shredding where steez1, creativity and mathematics collide.

1. Steez:

Noun (slang): A combination of style and ease.

“Dude, that tre flip had mad steez”

The Ollie:

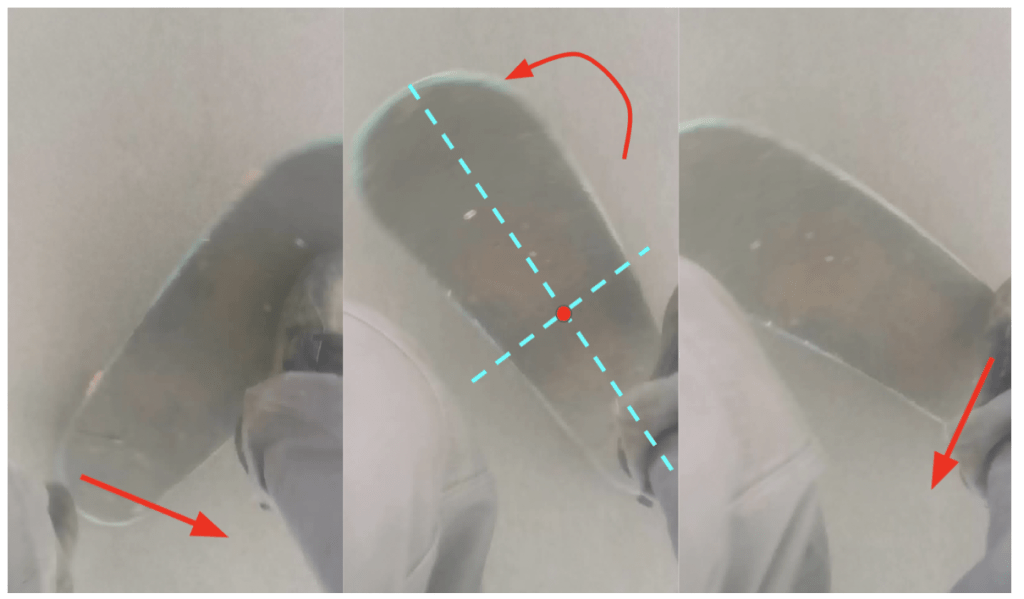

The foundational trick in skateboarding, the ollie, is the first trick everyone learns. It’s a method of propelling yourself into the air with the board. Below, is me doing an ollie, with key force arrows shown:

The ollie makes use of Newton’s third law and conservation of angular momentum. Initially, a downwards force is applied to the tail by your back foot and as a consequence of Newton’s third law, that every action has an equal and opposite reaction, the ground produces an upwards normal force of the same magnitude. This can be seen in the rightmost frame, denoted as the blue arrow. This normal force propels the skater and skateboard upwards.

The critical moment in executing the ollie occurs when the skateboarder “pops” the tail of the board. This action imparts a large enough force to propel you off the ground. By applying a torque (rotational force) with your back foot, you introduce angular momentum to the system, a measure of how difficult it is to stop something rotating. Momentum must always be conserved and so, this rotational force translates into upwards velocity.

In the central frame, the skater’s front foot applies a horizontal force to the deck2, denoted by the red arrow. This action serves to level out the board mid air, ensuring that it remains parallel to the ground. To control the orientation of the skateboard, the skater can manipulate their centre of mass, facilitating a smooth and controlled landing. As the skater’s mass is substantially larger than the board, adjustments can be made in the air, further enhancing stability and precision throughout the manoeuvre.

In the final leftmost frame at the peak of the jump, the force of gravity overpowers the upwards normal force, pulling both the skateboard and the skater downwards. Gravity acts as the dominant force accelerating them towards the ground. The outcome of the landing now depends on the skill of the skater. The safest way to land is on the bolts, above the wheels, as this is the most stable part of the board. Skateboarders will also bend their legs on landing to absorb the impact and maintain balance.

If you’re curious about how the skateboard remains attached to the skater’s feet, there’s a simple explanation. The force applied acts on both the board and the skater, so they rise at the same time at the same speed. At the apex of the jump, they are both subject to gravitational acceleration of the same magnitude, so they fall at the same time. There is a common misconception that the heavier something is, the faster it falls, but this is false; gravitational acceleration is independent of mass.

2. Deck:

Noun: The wooden, slightly concave, part of the skateboard that the skater stands on.

“Imma have to buy a new deck cause I totalled mine yesterday”

The Force Required for the Ollie:

Now, we can get to a more interesting part, calculating the normal reaction force needed for such a manoeuvre.

To determine the necessary force for executing the ollie, we first need to examine the video footage, note any key events and represent them on a diagram. Our next step involves calculating the times for each frame of the video. Given that the footage was filmed at 20 frames per second, calculating the time for one frame is straightforward:

20𝑓𝑝𝑠 ⇒ 1/20 = 0. 05 𝑠𝑒𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑑𝑠 𝑝𝑒𝑟 𝑓𝑟𝑎𝑚𝑒

With the number of frames corresponding to each key event noted, we can now calculate the duration of each interval and put them into our diagram:

Analysing the motion in two dimensions is simple, but we can make it even easier. We are only looking for the vertical force produced so we can rework our diagram to reflect this:

Now, let’s calculate the initial velocity to reach the peak of the jump at 0.25s. At h𝑚𝑎𝑥 the final velocity is zero, which means we can calculate the initial velocity, u, with only the time period and gravitational acceleration, a known value. We will do so via the equations of motion.

𝑣 = 0, 𝑎 = −𝑔, 𝑠𝑜 𝑣 = 𝑢 + 𝑎 𝑡 ⇒ 0 = 𝑢 − 𝑔 𝑡, ∴ 𝑢 = 𝑔 𝑡 = (9.81)(0.25) = 2.4525 𝑚𝑠−1

Having calculated the initial velocity required, how do we go about calculating the necessary force? First, we need to write an equation relating force to velocity:

𝐼 = △𝑝

𝐹 △𝑡 = 𝑚 𝑣 − 𝑚 𝑢

𝐹△𝑡 = 𝑚 (𝑣 − 𝑢)

In this step, I’ve utilised the impulse-momentum theorem and while that may sound complex, it’s actually very straightforward. It states that the Impulse, 𝐼, is equal to the change in momentum, ∆𝑝 (the little triangle, delta, indicates “change in”). Breaking this down further, impulse is the product of force and change in time. It represents the force’s effect over a specified duration. Momentum is a measure of how difficult it is to stop an object and so relies on mass and velocity. It is defined as 𝑝 = 𝑚𝑣. Change in momentum is the final momentum subtract the initial momentum. For our specific scenario, mass is constant and so has been factored out of the right-hand side.

Considering a combined weight of 70kg for myself and the board, and using the information that the downwards force application spans four frames, equivalent to 0.2 seconds, we can proceed with the final calculation. It is worth noting that the initial velocity we previously determined now serves as the final velocity, 𝑣, in this context. It represents the velocity resulting from the impulse. Since there was no initial vertical velocity before the application of the force, we take the initial vertical velocity, u, to be zero.

𝐹 (0. 2) = 70 * (2.4525 − 0)

∴ 𝐹 = 858.375 𝑁

This is equivalent to an 87.5 kg force! (858.375 ÷ 9.81 = 87.5 𝑘𝑔) This makes sense, as a force of at least 70 kg will be needed to lift off the ground. The other 17.5 kg is used to lift the skater and the board upwards.

Additionally, we can also calculate how much air3 I gained, with our earlier calculations of u and t at h𝑚𝑎𝑥:

𝑠 = 𝑢 𝑡 + (1/2) 𝑎 𝑡2 ⇒ 𝑠 = 𝑢 𝑡 − (1/2) 𝑔 𝑡2

= (2.4525)*(0.05) − (0.5)*(9.81)*(0.052)

∴ 𝑠 = 0.3066𝑚 ≈ 31𝑐𝑚

That’s some decent height, but the world record is 1.15 metres! For such a high jump, our modelling breaks down as the force required to do so would be around 170 kg. Though this may seem somewhat achievable, the video footage demonstrates that it’s more to do with the positioning of your legs than the force produced.

By lifting your legs up, almost touching your chest, you can maximise height and hence, perform a much higher ollie. Additionally, there are numerous factors at play that have been ignored in our analysis, such as air resistance, horizontal velocity and even the surface. For such an abnormal height, our modelling struggles to accurately predict the true outcome.

3. Air:

Verb: The amount of height gained when performing a trick.

“I’m literally getting zero air on the mini ramp, I need to learn how to pump properly”

The Kickflip:

Arguably the most renowned trick in skateboarding, the kickflip is another one of the fundamentals. Like the ollie, it harnesses the same normal force principle, to launch the rider and board upwards, but the difference arises in the motion of your front foot. While the ollie uses a vertical flick4, the kickflip makes use of a diagonal motion. By splitting this diagonal force into its 𝑥 and 𝑦 components, it can be seen that the 𝑦 force provides the “straightening” of the board, much like the ollie, and the 𝑥 force provides a torque to the right (from the perspective of the leftmost image). Here is a diagram displaying the 𝑥 and 𝑦 components of the diagonal force.

The torque produced from 𝐹𝑥 provides angular acceleration (rotational acceleration), in correspondence with Newton’s second law, 𝐹 = 𝑚𝑎. This, in turn, rotates the board 360 degrees until it’s facing upwards. At this point, the skater catches the board with their back foot to stop the rotation. This provides a force to the left, as can be seen in the third rightmost frame.

4. Flick:

Verb: The action of quickly moving your foot up the board to initiate a trick.

“You need more flick or you’re never gonna land that varial”

The Pop Shuvit:

The pop shuvit is another staple in boarding. Skaters don’t often come up with the most verbose names for tricks, they perhaps could have been more creative than “shuvit”! Above, the pop shuvit can be seen. The trick involves rotating the board 180 degrees and then catching it with your back foot. The principles are identical to the kickflip and ollie, but this time it’s the skater’s back foot providing the rotational force. The scoop5 provides a torque to the right, rotating the board. As with the kickflip, this force produces angular acceleration due to Newton’s second law. Once a 180 degree rotation has been completed, the skater’s front foot provides a force to the right to stop the rotation. The kickflip and pop shuvit use the same mechanics; the only difference is their axes of rotation, marked above as the blue dotted lines, which we will elaborate on in the next section.

5. Scoop:

Verb: The action of quickly moving your back foot to the side of the board to initiate a trick.

“I swear how do the pros scoop with so much power, they’re just on another level”

Stable Rotations, Principal Axes and Moments of Inertia:

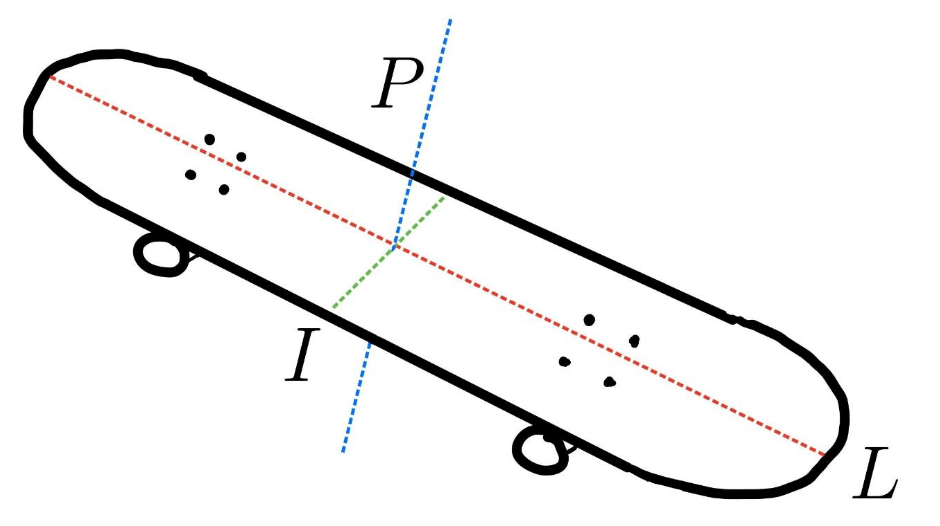

The kickflip and pop shuvit both involve stable rotations about one of the three principal axes. To explain the terms “stable rotation” and “principal axes”, let’s investigate the diagram below.

Here, the axes 𝑃, 𝐼 and 𝐿 represent the perpendicular, intermediate and long axes respectively. Typically, these are referred to as the minor, intermediate and major axes. However, for a more intuitive approach, we will use the above labelling. These are the three principal axes of any object, in this case a skateboard.

To discuss stable rotations, we first need to expand on what rotating “about” an axis means. Rotating about an axis refers to the axis that does not move. In the case of the kickflip, the axis of rotation is the long axis as it does not move during the board’s rotation. The long axis is the axis that the board rotates “about” for a kickflip. It gets slightly more abstract for the pop shuvit. The perpendicular axis comes out upwards from the board and, as it does not move during rotation, is the axis of rotation. The perpendicular axis is the axis the board rotates “about” for a pop shuvit. Understanding the principal axes is essential for a deeper understanding of the mechanics behind tricks like the kickflip and pop shuvit. By recognising which axis remains fixed during a rotation we can better analyse the dynamics of such tricks.

Now onto stable rotations. A stable rotation means that the applied force, to rotate in a specific direction, yields the intended outcome without any secondary motion. For instance when attempting a kickflip, it doesn’t inadvertently trigger a pop shuvit and vice versa. Stable rotations are essential for tricks like the kickflip and pop shuvit as without them, the skateboarder would have no control of the board. Seeing as these movements do not result in unforeseen circumstances we can conclude that rotations about the perpendicular and long axes are stable.

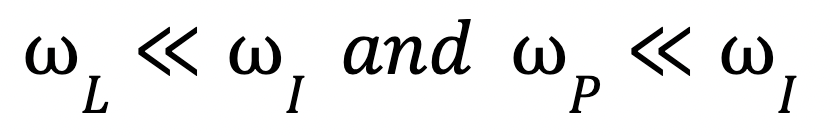

To dive deeper into the rotational dynamics, let’s introduce moments of inertia. Any skateboarder can tell you that executing a kickflip (360 degree rotation about the long axis) demands less force than a 360 pop shuvit (360 degree rotation about the perpendicular axis). But why is this the case? Why is it possible to perform double or even triple kickflips but nearly impossible to land 720 or 1080 pop shuvits? The answer lies in understanding the unique moments of inertia relative to the axes. First let’s define the moment of inertia. In simple terms, it is the distribution of mass relative to a point. In our scenario, it will be relative to the axes of the board. On a skateboard along the long axis, its moment of inertia is the smallest as its distribution of mass is the smallest from this axis. For the perpendicular axis, its moment of inertia is the largest; the mass is distributed the furthest from this axis. Briefly, it’s useful to note that not all objects have distinct moments of inertia, a ball for example has the same moments of inertia about each of its axes. Though as explained above this does not apply for our skateboard.

Now that we’ve grasped the concept of moments of inertia, let’s discuss why it’s much easier to execute a double kickflip than a 720 pop shuvit. A smaller moment of inertia results in a faster rotation, as it’s easier to spin. This is our kickflip. Conversely, a larger moment of inertia results in a slower rotation, it’s much harder to spin. We can express this relationship mathematically:

ω𝐿 > ω𝑃 ∵ 𝐼𝐿 < 𝐼𝑃

ω represents angular velocity, the speed of rotation, we will explore angular velocity in more detail later on. We can also see this relationship more directly in the equation for angular momentum, which again, we will investigate further in the next section:

𝐼 = 𝐿 / ω

Because 𝐼 and ω are inversely proportional to each other, as 𝐼 increases ω decreases and vice versa.

6. Double Kickflip:

Noun: A kickflip that involves the board completing two full rotations before landing.

“There’s no way you just did a double kickflip down that ten stair”

Vert* Skating:

Now that we’ve mastered the basics, it’s time to head to the park and tackle the ramps. However, before we drop-in7, we need to recap on some of the terminology introduced in the previous section. Understanding these terms will not only make the mathematics easier to follow, but will serve us well in later sections. First off, ω represents angular velocity. Angular velocity refers to the change in angle per second. Think of it as similar to linear velocity but, instead of a change in distance over time, it quantifies the change in angle over time. Earlier, it was defined as the speed of rotation, which is a quick, easy definition. Secondly, 𝐼 represents the moment of inertia, as we determined before, it is the distribution of mass relative to a point. It’s a crucial concept to understand as the essay progresses. Now, despite the detour we’ve taken, we’ve finally made it to the skatepark. It’s time to put some of our mathematical knowledge into practice and attempt some airs.

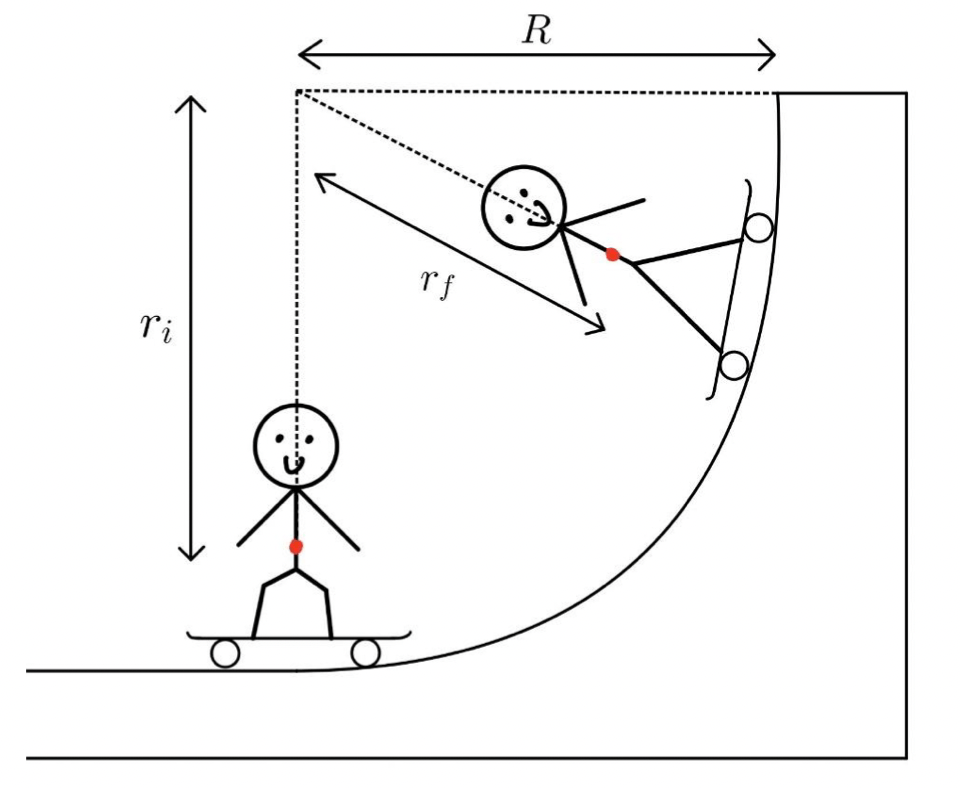

You may have witnessed skaters drop-in7 on a ramp and gain more height than should be possible. If you are familiar with the principle of energy conservation, that energy cannot be created or destroyed, you may find this puzzling. How is it possible to conjure up extra energy and go higher? Are skaters secretly tapping into some sort of free energy? Could they be the key to unlocking perpetual motion machines? Maybe if we could harness the energy created by a carving skater, we could have an endless source of free energy. Unfortunately, this is not the case. The apparent violation of energy conservation lies not in the realm of perpetual motion machines but in mathematics. To explore this mystery, we need to dive back into the maths and carefully analyse the diagram below.

First, we need to discuss the practical method to achieve greater height on a ramp. This is accomplished via a technique known as pumping. Pumping involves starting with bent legs at the bottom of the ramp and extending them at the peak of the ramp’s transition. To understand what this results in, we look to maths.

When riding a ramp angular momentum must be conserved. Let’s write out an expression for this, using subscripts 𝑖 and 𝑓 meaning initial and final respectively.

𝐿𝑖 = 𝐿𝑓

𝐿 here signifies angular momentum. We can substitute in the components of angular momentum, angular velocity and the moments of inertia to form:

𝐼𝑖 ω𝑖 = 𝐼𝑓 ω𝑓

We have two different moments of inertia, 𝐼𝑖 and 𝐼𝑓 because we are measuring them relative to the axis of rotation, where the three dotted lines in the diagram cross. The radius decreases as you go up the ramp, due to pumping, and so, we have two different values. The equation for inertia is 𝐼 = 𝑚𝑟2, so we will substitute this in:

𝑚 𝑟i2 ω𝑖 = 𝑚 𝑟f2 ω𝑓

In the diagram 𝑟𝑖 and 𝑟𝑓 are marked, we are making progress to where we want to be. The expression 𝑚 for mass can be cancelled as it’s on both sides of the equation and is constant. Let’s rearrange for the ratios of angular velocities to radii squared.

ω𝑓 / ω𝑖 = 𝑟i2 / 𝑟f2

Now a quick substitution of ω = 𝑣 / 𝑟 , and we get to a useful form of the equation:

𝑣𝑓 / 𝑣𝑖 = 𝑟𝑖 / 𝑟𝑓

In the diagram, when the skater first bends their legs they have a large initial radius, 𝑟𝑖. As the skater reaches the peak of the ramp, they extend their legs and decrease their radius to 𝑟𝑓. While the diagram may not be perfectly to scale, it should be clear that 𝑟𝑖 > 𝑟𝑓 . If we examine the equation we derived, we can see that the speed gained is directly proportional to the radius. So, the amount that the skater can bend and extend their knees, adjusting their radius, affects their velocity. By looking further into the equation, we can see that the final velocity and final radius are inversely proportional. This means that as 𝑟𝑓 decreases compared to 𝑟𝑖 , 𝑣𝑓 increases compared to 𝑣𝑖 . Because 𝑟𝑓 does in fact decrease relative to the initial radius when pumping, final velocity, as expected, increases. This is how pumping works. This surge in velocity results in propelling the skater to significantly greater heights. However, the source of this energy remains unaddressed. If you haven’t connected the dots, the extension and compression of the skater’s legs is where the work is being done. You can picture it as energy being pumped (literally) into the system; the skater isn’t gaining any free energy but rather, by exerting a force and doing work, is increasing the total energy of the system.

To see the impact pumping actually makes to kinetic energy (energy of motion), we can derive another equation. After further substitutions, we arrive at the following relationship:

𝐸𝑘𝑓 / 𝐸𝑘𝑖 = 𝑟𝑖2 / 𝑟𝑓2

This provides additional insight into how much energy is gained in each pump. Once more, if 𝑟𝑓 is smaller than 𝑟𝑖 then the ratio of kinetic energies yields a value greater than one, meaning additional kinetic energy has been gained.

Now let’s move away from the algebra and estimate a value for the amount of kinetic energy actually gained per pump. We need some data first.

A full size half pipe is 4.3𝑚 tall with roughly 0.6𝑚 of purely vertical ramp. Let’s take the average skater’s height to be 1.7𝑚. A quick google will tell us that the average centre of gravity is:

0.56 × height

Which puts our skaters centre of gravity (the red dot on the diagram) at:

0.56 × 1.7 ≈ 0.95 𝑚

We also need to consider the height of the board, about 0.1 𝑚, so:

0.95 + 0.1 = 1.05 𝑚

Now, let’s say when bending their legs the skater reduces there centre of mass by twenty percent, remember this won’t change the height of the skateboard:

0.8 * (0.56 × 1.7) + 0.1 ≈ 0.86 𝑚

We also need to calculate the radius of the half pipe. The ramp has 0.6𝑚 of vertical so, if we model the ramp as a quarter of a circle, we need to subtract this from the total height to find the radius:

4.3 − 0.6 = 3.7 𝑚

Now to find 𝑟𝑖 and 𝑟𝑓 , the initial and final radii. We will do this by subtracting the skaters centres of mass at the final and initial times:

𝑟𝑖 = 3.7 − 0.86 = 2.84𝑚

𝑟𝑓 = 3.7 − 1.05 = 2.65𝑚

Finally, we are at the stage where we can plug it into the equation derived earlier:

𝐸𝑘𝑓 / 𝐸𝑘𝑖 = 2.842 / 2.652 ≈ 1. 15

What this tells us is that for each pump the skater gains 15% more kinetic energy! We’ve made a few assumptions and ignored friction so in reality the value would be a little lower, but this is still a good ball-park (skate-park?) estimation.

* Vert skating refers to riding steep ramps in a skatepark. Vert is a shortened version of vertical.

7. Drop-in:

Verb: The act of leaning into a ramp from the highest point and rolling down it.

“I don’t think you can drop-in on that its way too high”

The Centrifugal Force and Vert World Records:

With each pump increasing kinetic energy by 15 percent, why don’t skaters keep going forever and reach phenomenal heights? That would definitely make for some cool lines8. Despite some skaters wanting to do just that, Newton’s laws intervene through the centrifugal force. The centrifugal force pulls you away from the axis of rotation and although some argue it’s a fictitious force, if you construct Newton’s laws in a rotating reference frame, the force can be seen. Let’s examine the equation for centrifugal force:

𝐹𝑐𝑓 = 𝑚 𝑣2 / 𝑟

From this equation, we can deduce that as your speed increases, so does the centrifugal force acting upon you. As velocity is squared in this equation, doubling your speed results in a quadrupling of the force you experience. This leads us to the realisation that, while each pump yields a 15% increase in kinetic energy, it also brings about a significant escalation in the centrifugal force.

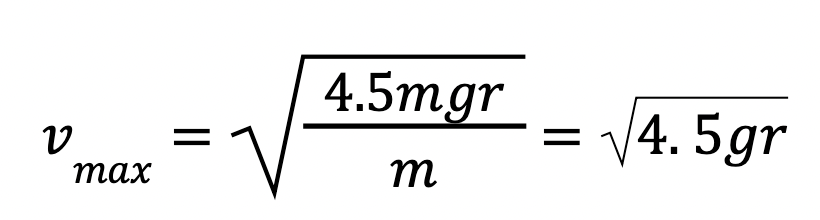

With a higher centrifugal force pushing you into the ramp it makes it progressively harder to extend your legs and so after a certain point it becomes impossible to gain more speed and height. Research suggests that the maximum force a person can withstand while still extending their legs is around four times their body weight, or 4gs. By establishing the threshold as slightly above this, 4.5g, we can rearrange the equation for centrifugal force to calculate the maximum speed and then maximum height, attainable under these conditions.

𝐹𝑐𝑓 = 𝑚 𝑣2 / 𝑟 ⇒ 4.5 𝑚 𝑔 = 𝑚 𝑣2 / 𝑟

Rearranging for velocity and cancelling any common terms gives us:

Now, plugging in the values for gravitational acceleration and the radius of the ramp from earlier:

∴ (4.5 × 9.81 × 3.7)^1/2 ≈ 13 𝑚𝑠−1

This equates to roughly 28 mph and though this may seem rather quick at first glance, anyone who’s witnessed skaters on a ramp will know they often approach very fast speeds, similar to the one above.

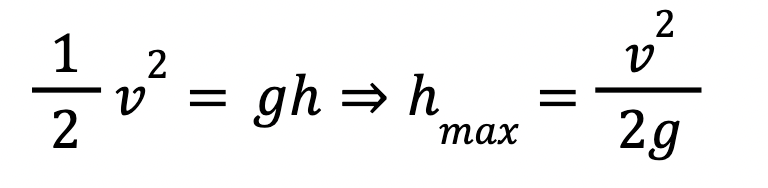

From this, we can calculate the maximum height using energy conservation. If we assume all kinetic energy is converted to gravitational energy we can find h𝑚𝑎𝑥.

Rearranging for the desired expression, after cancelling mass:

Here we can plug in the expression for velocity we found earlier in terms of 𝑔 and 𝑟:

This gives us an equation for the maximum height reached, plus the height of the ramp. So, if we subtract the height of the ramp we get the true value for how much air can be achieved:

Now that we have our maximum possible value for height, 4.025 𝑚, we can construct a graph to display our predictions compared to the real results. To do this we need to express h𝑟𝑎𝑚𝑝 in terms of 𝑟. We know that it will be greater than 𝑟, as the half pipe has a vertical section. If we assume that every half pipe has similar construction to the conventional halfpipe we used in our above calculations, we can find an expression for h𝑟𝑎𝑚𝑝. For our conventional half pipe, we had 0.6 𝑚 of vertical and a radius of 3.7 𝑚. h𝑟𝑎𝑚𝑝 will equal 𝑟 + h𝑣𝑒𝑟𝑡𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑙 so we need to find h𝑣𝑒𝑟𝑡𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑙. This is merely the ratio of vertical height to the radius. So, we get our final result as:

Now we can plot this on a graph:

Above, we have plotted the achieved world record, predicted maximum and highest air on a mega ramp. Looking at our predicted maximum and the achieved world record they are very close, our predictions almost match the result exactly. We have not accounted for air resistance and other factors, which would decrease our gradient, so it’s likely that the conventional halfpipe world record is unlikely to be broken. If it is, it’s likely to only be by a few centimetres.

There seems to be a moderately large discrepancy in the predicted and result of the highest air achieved on a mega ramp. In actual fact, mega ramps operate differently from standard halfpipes, causing our modelling to break down. Furthermore, lacking precise dimensions for the radius of the mega ramp adds another level of complexity to our analysis. Consequently, the discrepancy between our prediction and result is not entirely surprising.

However despite these modelling challenges, there is optimism regarding the potential for breaking the highest air world record. Skaters prioritise safety when riding such dangerous ramps (as they should), which may result in less emphasis on maximising pumping. By looking at the graph, there is a large gap between the highest air and predicted value so it should be plausible that in the future, increased experience on such daunting ramps, could lead to surpassing the current record by a significant margin.

8. Lines:

Noun: A sequence of tricks or movements performed in succession.

“Let’s go carve out some sick lines in the bowl”

The Intermediate Axis Theorem:

In the stable rotations section, we omitted an explanation for the intermediate axis and its effect on rotation. The reason for this is because it does not result in a stable rotation, it’s unstable. In this section we will explore the intermediate axis theorem, or what happens when you rotate about the intermediate axis.

To introduce the intermediate axis theorem, I recommend trying this quick practical example:

Take your phone and carefully rotate it “kickflip style”. As you may recall this corresponds to rotation about the long axis. You will notice that it will do as you expect, it’s a stable rotation. Now take your phone and carefully rotate it “pop shuvit style”. This corresponds to rotation about the perpendicular axis. It’s an example of a stable rotation. Now comes the strange part and the crux of the next few sections. Hold your phone flat in your hand, screen upwards, and flip it about the intermediate axis. Here’s a diagram demonstrating the flip you should conduct. You are aiming for a full rotation, not just 180 degrees.

If you’ve performed this manoeuvre successfully, you will notice that your phone lands back in your hand but with the screen now facing down. It may take a few attempts to get this result. It has completed an additional half turn in the air, experiencing the effects of the intermediate axis theorem. So why does this happen?

To examine this question we need to understand the mechanics of the theorem, I will explain via an intuitive approach. This may be challenging to grasp, so don’t worry if you don’t understand the concepts the first time. Once the famous physicist Richard Feynman was asked if he could intuitively explain the intermediate axis theorem. He is commonly known as the great explainer because of his ability to explain concepts in a simple, intuitive way. Feynman thought for a while and finally said, no, there’s no intuitive explanation for the theorem. I’ll try to prove him wrong, but bear in mind this is a monumental task.

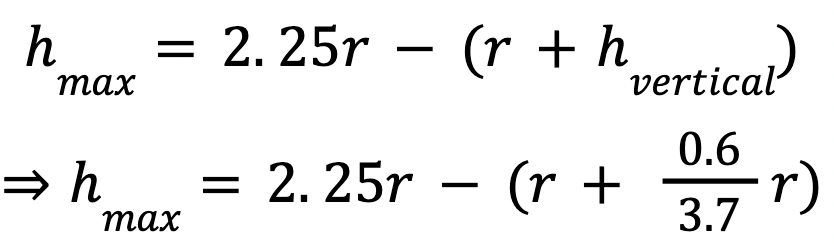

Picture a thin massless disk with two heavy masses at the opposite ends of this disk. Now imagine two more lighter masses on the other two corners of the disk. Each of the axes need a different moment of inertia to see the effect of the intermediate axis theorem. You may remember from earlier that the long axis has the smallest moment of inertia, the perpendicular has the largest, and unsurprisingly the intermediate axis has the intermediate moment of inertia. Marked on the diagram below are the axes of rotation that we are familiar with.

If we spin this disk about the intermediate axis we will see centripetal forces acting inwards on the heavier masses. Centripetal forces “pull” the object towards the axis of rotation, the intermediate axis.

Here is where it gets complicated. If we take our reference frame to be spinning with the disc, the centripetal forces of the heavier masses are counteracted by the centrifugal forces, pushing them away from the axis of rotation. If we look at the smaller masses, we can see that they experience centrifugal forces as denoted on the diagram. They have no centripetal force, so the centrifugal force is the only force acting on them. Because centrifugal forces push an object away from the axis of rotation, the smaller masses experience acceleration due to 𝐹 = 𝑚𝑎. The centrifugal force is denoted as 𝐹𝑐𝑓 in the diagram.

This centrifugal force gets larger as the smaller masses rotate away from the axis of rotation until they reach the peak of the rotation. Then the forces decelerate the smaller masses, causing them to return to their equilibrium position. During the first half of the turn, they accelerate the smaller masses upwards. Then, during the second half, the centrifugal forces decelerate the masses. This process then repeats indefinitely.

Hopefully this explanation and diagrams have provided a solid foundation, it’s a very challenging concept to visualise. But how does this actually apply to doing some gnarly9 tricks?

9. Gnarly:

Adjective: A very challenging or impressive trick.

“Holy smokes, that was gnarly. The tech wizard’s back at it again”

The Impossible and Euler’s Equations on Rigid Body Dynamics:

One trick revolutionised skateboarding in the 80s, paving the way for numerous variations in the coming years. This trick was named “the impossible”. It’s easy to see where it got its name, it was deemed an impossible trick. To introduce the impossible, we will relook at the axes of the skateboard.

As you may have guessed, the impossible involves a rotation about the intermediate axis:

You can see above that the board does not undergo an unstable rotation, as we would expect. Instead, it performs a stable spin. However we have learnt that rotation about the intermediate axis is unstable, so how do skaters manage to pull off such a trick? To investigate, we need a deeper understanding of the mathematics at play.

Hopefully you’ve been taking notes because it’s here where the mathematics really starts to ramp up (see what I did there). If you struggled to visualise the “intuitive” explanation and are more familiar with mathematical methods, this should provide you with the basis to understand the intermediate axis theorem.

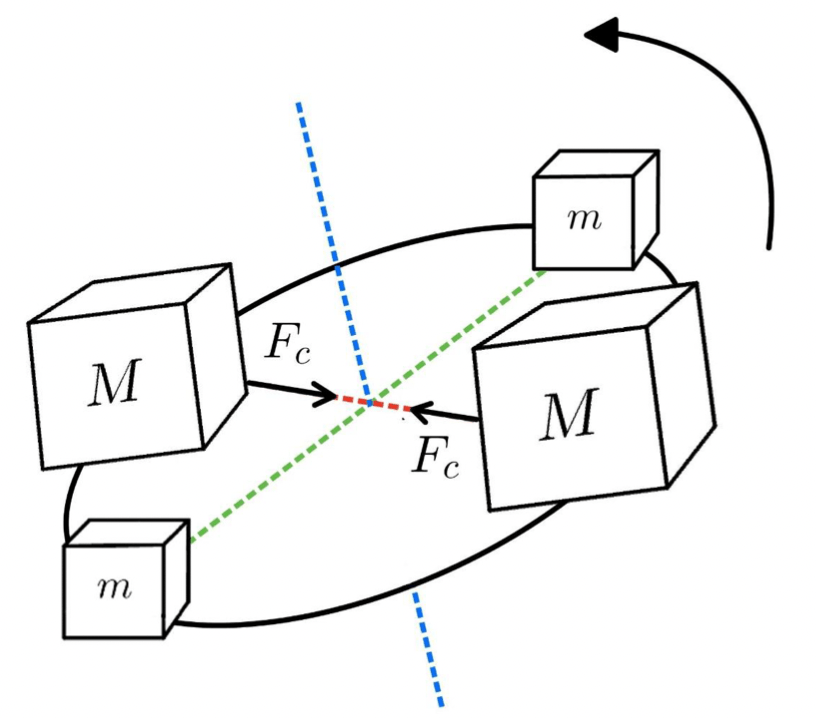

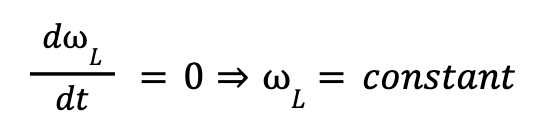

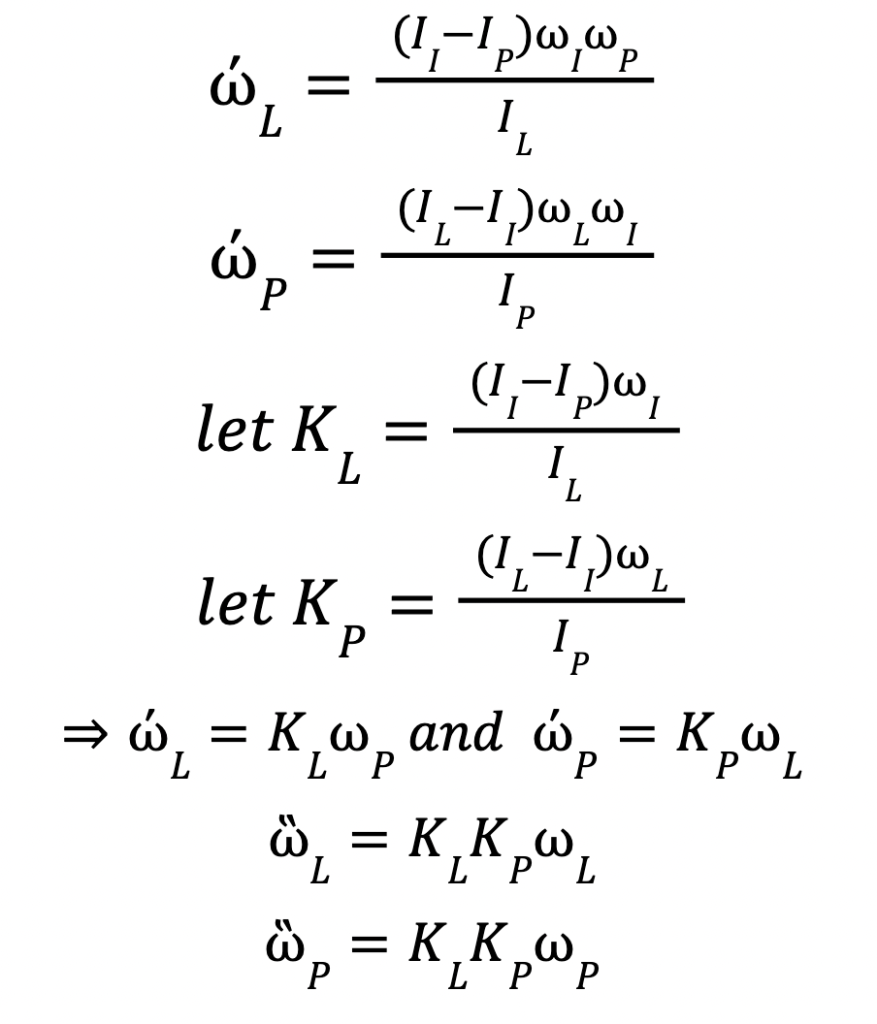

To begin we need to examine Euler’s equations on rigid body dynamics. They look like this:

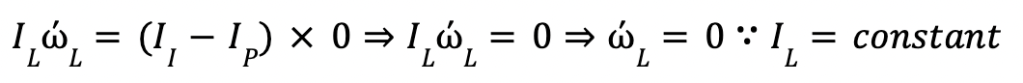

First let’s explain the symbols, you may recall us discussing moments of inertia, this is what 𝐼 denotes. ω is angular velocity and ώ is the rate of change of angular velocity or the derivative with respect to time. This tells us how the angular velocity changes as time passes. The subscripts 𝐿, 𝐼 and 𝑃 denote the long, intermediate and perpendicular axis respectively.

To get a taste for what these equations actually mean, let’s look at the first equation, rotation about the long axis, kickflip style.

Because we are spinning about the long axis, the other angular velocities are negligible:

This, in turn, means that our equation for rotation about the long axis essentially becomes zero:

This tells us even more; that the angular velocity about the long axis must be constant. This is because of the time derivative. If the rate of change of angular velocity is zero, the angular velocity has not changed throughout the rotation:

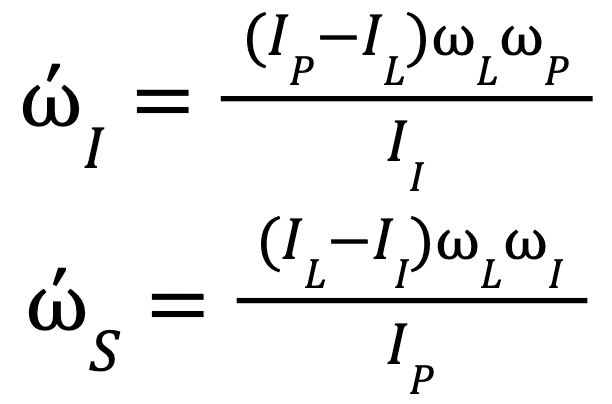

We can use this newfound information in the previous two equations to find the impact of the short and intermediate axes when rotating about the long axis. If we rearrange them both for their time derivatives we get this:

Because, as we found out earlier, ω𝐿 is a constant (and so are the moments of inertia) we can make our equations less unwieldy by substituting 𝑘𝐼 and 𝑘𝑆.

Now, our equations are much simpler. We have:

Here is where it starts getting rather complicated. We first need to find the second derivative of these equations (the rate of change of the rate of change of angular velocity). Here ὣ denotes the second derivative with respect to time.

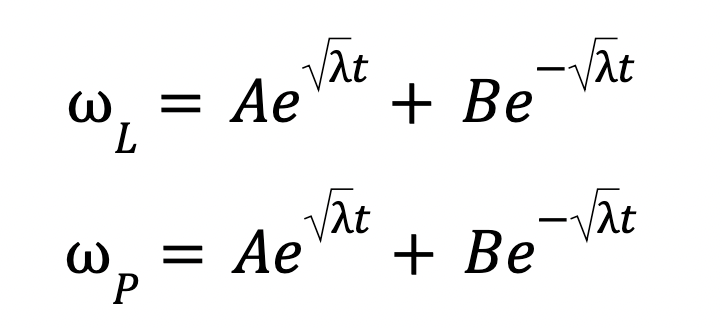

𝑘𝐼𝑘𝑃 is less than zero here so we can get down to solving this second order differential equation. This is rather mathematically challenging and the process isn’t essential for understanding the result, but if you are interested I have included the steps. As the solutions to ω𝐼 and ω𝑃 are identical, I have omitted the subscripts for the working.

Now with the subscripts:

Now what does this actually tell us? What this result means is that the intermediate and perpendicular angular velocities oscillate around their original values as time progresses when undergoing rotation about the long axis. This means that they do not disturb the rotation, due to the nature of sin and cosine, and hence it is a stable rotation. We can do this all again for the rotation about the perpendicular axis “pop shuvit style”, but I’ll spare you the mathematics, it results in the same thing but with ω𝑆 replaced with ω𝐿. So now we know for sure that rotation about the perpendicular and long axes are stable, backed by mathematics.

If you are familiar with mechanics, you may notice that the differential equation I solved above is essentially the same as simple harmonic motion. Pendulums with a small angle undergo simple harmonic motion with their oscillations, so a good way to think about the variation in angular velocities is by picturing a pendulum. They increase slightly and then decrease again only to repeat indefinitely. As a whole this does not impact rotation about the long or perpendicular axes.

So where does the difference arise for the intermediate axis? Well, we start as we did before:

Once more, because we are spinning about the intermediate axis the other angular velocities are negligible.

As we did before we can come to the conclusion that the angular velocity of the long axis is constant.

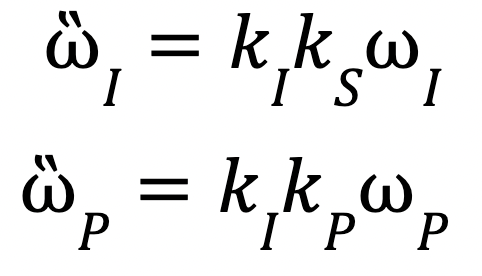

Again, we rearrange for the time derivative of the velocity and take the second derivative:

Unlike before 𝐾𝐿𝐾𝑃 is always greater than zero and this is where the imbalance lies. In our previous analysis 𝑘𝐼𝑘𝑃 were always less than zero. Now let’s see what happens when we solve this differential equation. I’ve left the working, but like before it’s not essential to understand the result. As before subscripts are omitted in the working as the solutions are identical in both cases:

Now putting our subscripts back in:

This is an exponential equation. Which means that the angular velocities, ω𝐿 and ω𝑆 grow exponentially (faster and faster and faster) as time progresses. This is what results in the abnormal rotations when spinning about the intermediate axis. Unlike the previous example of stable rotations where the angular velocities oscillate about their original values, rotations about the intermediate axis result in the angular velocities of the other axes increasing more and more. This is why the intermediate axis is unstable. This is the cause of the intermediate axis theorem.

So what does this mean for the impossible then? As we’ve just seen rotations about the intermediate axis are unstable, we’ve shown this in three different ways. So how on earth can skaters just ignore that? We’ve clearly proved that it’s unstable. Well sorry to be anticlimactic here, but all skaters have to do to counteract this abnormal rotation is to move their foot along with the board. If you reexamine the footage of an impossible you will see the skaters foot following the boards rotation. If this wasn’t the case the board would undergo unstable rotation. However this isn’t the end of the story for the intermediate axis theorem in skateboarding, there are actually many tricks that utilise it. Freestyle10 skateboarding makes use of the intermediate axis theorem in a number of tricks. Due to the nature of freestyle, a lot of the tricks don’t have specific names, but if you are familiar with skateboarding jargon I can tell you that the casper flip, pressure flip, and any many tricks from darkslide make extensive use of the intermediate axis theorem.

10. Freestyle:

Noun: A subcategory of skateboarding that involves more classical and creative tricks.

“I’m done with street, I’m gonna focus on freestyle from now on”

Conclusion:

That brings us to the end of our investigation on the applied mathematics of skateboarding. You’ve learnt your first ollies, kickflips and shuvits. You learnt how to pump on the ramps and even had a shot at the impossible. Now you can see how interlinked mathematics and skateboarding truly is. Knowing of it can even make you a better skater. You can harness the power of mathematics to stick more tricks, get higher airs and use the intermediate axis theorem to your advantage to land some truly rad11 tricks. There’s also plenty of mathematical evidence backing a new highest air world record, maybe you should give it a go! There’s still many ideas we haven’t explored but for now, enjoy shredding and remember the mathematics behind the scenes when you next pop an ollie.

11. Rad:

Adjective: An impressive, difficult, exciting or noteworthy feat.

“You read that skateboarding maths essay? Maths isn’t normally up my street but it was crazy rad”

Additional information:

Desmos graph link for those interested: https://www.desmos.com/calculator/bchlcjyxjk

Acknowledgments:

Thank you to Miss Chrisp for teaching me how to solve second order differential equations, despite it being next year’s content, and reading through the essay to check it’s up to scratch. Thank you to Mr Zamblera for reading through the essay and checking some of the more complex calculations.

References:

All images and diagrams are my own apart from the impossible and highest ollie footage.

The Impossible: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tT5dlPf4tVs

Highest Ollie: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eaxWggcACkc

Centre of Gravity Estimation: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/mathematics/center-of-gravity

Half pipe data: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Half-pipe

Terence Tao’s explanation of the intermediate axis theorem: https://mathoverflow.net/questions/81960/the-dzhanibekov-effect-an-exercise-in-mechanics-or-fiction-explain-mathemat

[…] TRM Essay Competition 2024: Student (Under-18) WinnerTRM Essay Competition 2024: Adult (Over-18) WinnerTRM Essay Competition 2024: Winners Shortlist […]

LikeLike