Joe Leach

In the first article I hinted towards there being more to say about the maths of the tube map, and as a man of my word, it’s time to talk about abstraction in graph theory. Building from the ground up, (as is generally advisable when building), what is a graph? Unlike the graphs we’re used to in science, in maths a graph is simply a collection of points (vertices) with connecting lines (edges), from some to others. Take note of the names: vertices and edges, I wonder if that signifies anything…

If you want to think of it like the tube map with stations and train lines connecting each one, go ahead, though I warn you: it’s completely possible to have a “station” that doesn’t connect to any others, or train lines from a station to itself. These are not ideal from a logistical standpoint but completely fine within our abstract mathematical world.

Next, why do we care? Mathematicians are interested in graphs because it turns out, through the magic of abstraction, lots of things can be interpreted as graphs. That means that if we understand graphs, suddenly we understand anything we can model as a graph, whether that’s gas pipes between houses, train lines between stations or even friendships between people. But what properties do graphs have, and what problems can they solve?

Let’s say you’ve been tasked with designing a circuit board. You know which components need to be on it, and which others they need to be connected to. There’s just one problem: you can’t cross the connection “tracks”, or you’ll cause it to short circuit. When can it be done?

Well, the position of each component doesn’t matter, only the connections between them must be preserved. Therefore, this is perfectly modelled as a graph. In fact, we want to find a planar graph – a graph that can be drawn without any lines crossing. This is what we’re looking for in our circuit board. Can you find a way to solve it for the setup described below?

Component Connects to

1 2, 3, 5

2 1, 4, 5

3 1, 4

4 2, 3, 5

5 1, 4, 2

Drawing it out as a graph we get the following:

Not planar since several lines cross. But, since we can move the points as we please, – remember only the connections are important – we can also do this:

Which is planar! Now, say we want to add in another component, component 6, that connects to components 2, 3 and 5. If we add this to the our first attempt we obtain:

Following our methodology from before, can we move the vertices around to obtain a planar graph solution?

Trying it for yourself a few times, you might come to the conclusion that it probably can’t be done. But, we’re mathematicians. We’re not be satisfied with “probably”. What if we had a graph with 80 vertices? It would take forever to work it out if it was planar, and you’d never know if you’d missed something. Which begs the question: can we decide exactly which graphs are planar and which aren’t with a general rule? Well, we can – but first we’ll have to introduce some terminology.

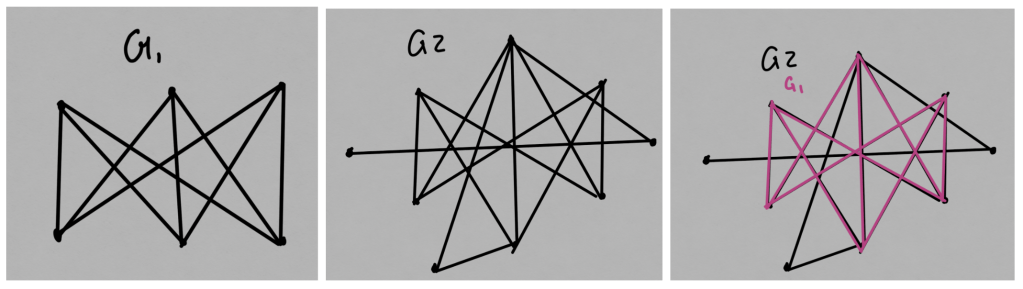

A graph G1 is a subgraph of another graph G2 if we can find the vertices and edges of G1 within G2. Here’s an example:

This is important because if G1 is non-planar, and G2 “includes” G1, then it surely also can’t be planar – it’s not possible to make a graph planar by adding more vertices and edges. This idea motivates looking for the “smallest” (least vertices and edges) possible non-planar graphs, since anything with this as a subgraph must also be non-planar.

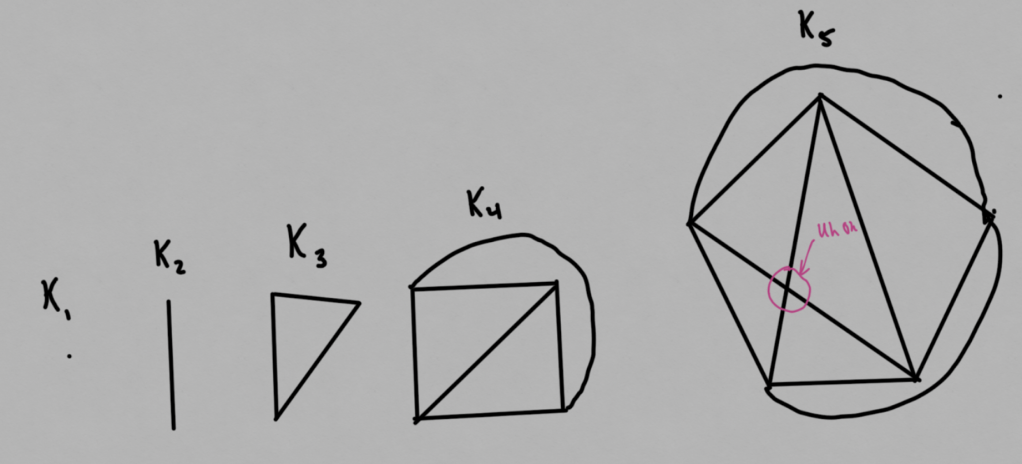

In seemingly the opposite direction, we define a complete graph as a graph where every vertex connects to every other vertex. Standard practice denotes the complete graph with n vertices as Kn. Here is K6 as an example.

Now for a small task. Try to draw out the first 5 complete graphs (with 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 vertices respectively) with as few lines crossing as possible. You should get something a bit like this:

Notice how we can draw the complete graph with 5 vertices with only one line crossing, but not with zero. It is no longer planar.

Okay, so what can we say about graphs with 5 vertices that aren’t complete? Can they be non-planar? Why/Why not? [Answer at the bottom of the article.]

Interesting, so the complete graph with 5 vertices is the non-planar graph with the least number of vertices. No other 5 vertex graphs are non-planar, but could there be another non planar graph with more vertices but less edges?

Indeed there is, though it’s a little less obvious. Given six vertices, split them into two groups of 3 and then simply connect each member of the first group to all the members of the second group. This type of graph, with two groups of vertices, is known as a Bipartite graph.

This graph has only nine edges and is non-planar – and notice that adding component 6 in our original diagram made the above graph K3,3 a subgraph of it.

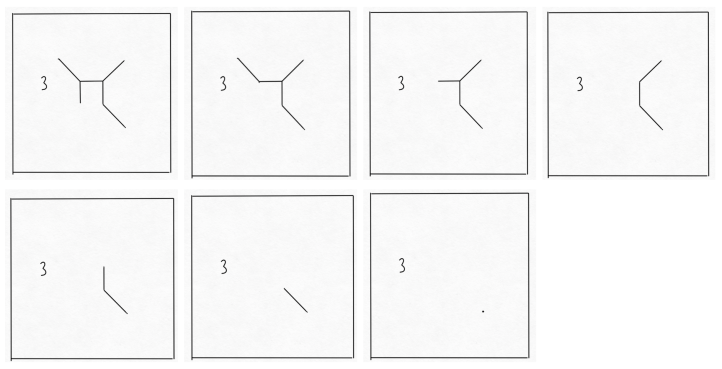

Now all the pieces are in place, the eager amongst you may already be thinking that a graph is planar only if it has one of the above graphs as a subgraph of it. This is close to the truth but let’s not get ahead of ourselves. There’s still one small problem: what if I just put a vertex in the middle of an edge somewhere like this?

This is called a subdivision and it’s clearly still non-planar, but doesn’t have either of the earlier graphs as a subgraph. Uh oh – our previous hypothesis is broken.

Fortunately this is an easy fix. This graph is essentially the same as the one without the extra vertex, right? So we just need to include these in our hypothesis: a graph is non-planar (can only be drawn with at least one crossing) if and only if it contains one of the above graphs (K5 or K3,3 here, but there are others more generally), or a “subdivision” of them as a subgraph.

We have by no means proved this, but perhaps you can understand why it must be true: there is some sense in which the graphs we’ve talked about are the “smallest” non-planar graphs, and all other non-planar graphs are built up from them, or a subdivision of them.

Now, it’s not entirely clear why they must contain these, in that regard, all I can offer you is the idea that essentially these are the only minimal non-planar graphs, that is, any other non-planar graphs may have edges or vertices removed and will remain non-planar. If you want more rigour, the theorem is known as Kuratowski’s Theorem, and the proof can be found online.

Returning to our circuit board example (that feels like a long time ago…), we can now easily see which sets of components and connections will work for small graphs. And for very large graphs, a computer can work it out pretty quickly using an algorithm. So, what started as a horrible question that, for 80 components, would require an awful lot of moving around of vertices, is now simply a matter of plugging the graph into an algorithm and receiving an answer.

Now that we’ve looked at a useful practical application of graph theory, we’re going to travel back to the very first abstraction into graph theory – the famous “Bridges of Königsberg” problem. The set up is as follows. Imagine you’re a citizen of Königsberg and one day you’re rather bored. You want to go on a walk but – being mathematically minded – you’ve decided that you want to cross each of the seven bridges of the city exactly once on your walk.

Given the map of the city below, can you plan such a route? (If you want to give this a go the islands are helpfully labelled A, B, C, D – the vertices – and the bridges are simply the edges between them.)

If you can’t find a solution, don’t worry, nor could the citizens of Königsberg. Fortunately for them, they knew someone who just might be able to help; and so it was that Leonhard Euler (yes, that Euler) set his mind to this bizarre problem. His solution was as follows.

Let’s consider the graph below where each vertex, A,B,C,D is a land mass and the edges are bridges between them.

With this setup, our walk may simply be represented as a list of letters (note the power of abstraction in simplifying the problem). Keeping in mind that we want to cross all seven bridges exactly once, how long will the list of letters be? [scroll down for the answer]

.

.

.

[Answer: eight letters long]

So, can we make such an eight letter walk? Start by looking at vertex A; how many times must A appear in the list? There are five bridges from A and each one we go over, we’re either going to or from A. This means A must occur in the list three times (can you see why?). Likewise, B, C and D all have 3 edges and so must occur 2 times, but 3 + 2 + 2 + 2 = 9 and we needed eight letters in our list; thus, it cannot be done.

Euler’s proof is interesting, but not incredibly illuminating as currently written, so let’s deal with this via a slightly different method to make the general result a little clearer. Consider a walk that does not start or end at A, and goes over each edge exactly once, what would be able to say about the number of edges connected to A? [scroll down for the answer]

.

.

.

[Hint: if you don’t start or end at A, every time you go to A you must also leave]

.

.

.

[Answer: there must be an even number of edges]

So for a successful route, we must start or end at A as it has 5 edges connected to it. But, here’s the twist. B, C and D also have an odd number of edges (bridges) connected to them so the walk must also start or end at each of those. Obviously the walk can only start at one place and end at another, so it’s impossible. Not only that, but through examining the proof you can say exactly when it would be possible for a general configuration of landmasses and bridges. (If you can’t see it think about the maximum number of vertices with an odd number of edges connected to them that you can have.)

Now we’ve been introduced to the great man, let’s dive into this work a little further. When he first created this particular topic, Euler called Graph Theory the “Geometry of Positions”. So, a natural question might be to ask how can we apply this ‘new’ geometry to the geometry that we know and love? To illustrate this I’d like to run through a cool proof of a theorem in Geometry, named Euler’s relation. The theorem is stated as follows.

For a convex polyhedron: V + F = E + 2

Where V is the number of vertices, F is the number of faces and E is the number of edges of the convex polyhedron in question.

First up, what is a “convex polyhedron”? A convex polyhedron is simply a 3-D shape with flat faces/straight edges that doesn’t have any “dents” in it (Think: cube, triangular prism or basically any other standard flat faced solid).

The proof of Euler’s relation goes as follows:

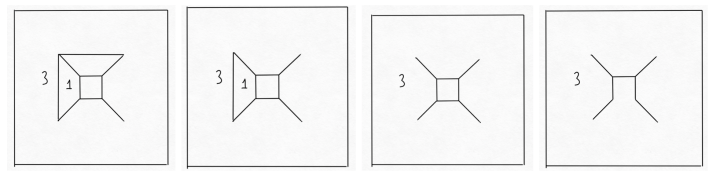

“Remove” the top face of your polyhedron so it is like an open box, now draw the rest of your shape “flattened out”.

For the rest of this proof we shall treat the “outside” of the net to be the face we just removed. Notice that now we have a planar graph: faces are regions, vertices are, well, vertices and edges are edges (hence the terminology).

Now if we remove an outside edge, two regions merge, like so:

After removing an outside edge each side of the equation, V + F = E + 2, is decreased by 1. Thus, if it was true before, it should still be true, and vice versa.

Repeating this process until we only have the “outside” face we are left with a set of vertices connected by edges (diagram 4 below). However, note that as we have only the outside face remaining, there cannot be a cycle (a “loop” of vertices), and so we must have at least one vertex connected to only one edge. Can you see which one this is in the diagram below?

Removing this vertex and this edge, both sides of the equation decrease by 1. There will still, of course, be no cycles. So we can repeat this, removing an edge and a vertex at a time until there are no more edges.

This will leave us with one vertex (as every edge must be between two vertices and we only remove one vertex at each step), as well as the “outside face”. At this stage we therefore have V=1, F=1, E=0 and the equation holds. Then, working backwards, the equation must’ve held initially as everything we did affected each side of the equation in the same way. Thus, the proof is complete.

Looking back over the proof, you can see that for this problem, somehow the actual “shape” of the shape we worked with was unimportant, and so we ignored it. Focussing on the edges and vertices as a graph made each step more logical and simple than if we had tried to remain in three dimensions. The link I pointed out earlier between the terminology of vertices and faces is actually slightly deeper than I let on; this is by no means the only problem in which we consider 3-D solids as a graph. These 3-D solids are essentially equivalent to the graph (net) that represents them. But that, is a story for another day…

[Answer: They’re all planar, as they’re subgraphs of the complete graph with 5 vertices with one edge removed, which is itself planar.]

Read the next article in the series here.

[…] Read the next article in the series here. […]

LikeLike

[…] Article 1: The Path Towards Higher Mathematics is Guided by AbstractionArticle 2: Abstraction and Graph Theory with Euler […]

LikeLike

[…] 1: The Path Towards Higher Mathematics Is Guided By AbstractionArticle 2: Abstraction and Graph Theory with EulerArticle 3: What is a vector […]

LikeLike