John Winmill-Briggs

1 The Game

Imagine standing at the origin (0,0) of a Cartesian coordinate system; at each lattice point, a point with integer x and y coordinates, there is a tree (see Figure 1). Now imagine that you shine a laser into the forest. What is the probability that you hit a tree without hitting any other trees along the way? Rather, what is the probability that a ray extended from the origin, stopping at the first lattice point at which it meets, intersects a lattice point (see Figure 2)?

At first glance, it may seem that this game has a basic answer. We know that there are infinitely many directions in which you can extend a ray from the origin, and, on a small scale, it appears that usually these rays miss the lattice points around the origin. Therefore, intuitively, the answer must be 0, right? Although this line of reasoning makes sense when looking at a finite set of points, if you start zooming your view out, you see that the ray meets more and more lattice points, giving way to a far more beautiful and exciting answer!

If you play around with this game, you can begin to notice a pattern. Each time that the ray intersects the first lattice point, the modulus of the x and y coordinates have no common factors with each other, excluding 1; they are coprime! If you ponder this fact further, you will see that it must be the case.

If the point you are on has x and y coordinates that are not coprime, you can deduce that the ray to that point must have already intersected a lattice point with coprime coordinates by dividing the x and y coordinates by their common factor (see the green line on Figure 2).

Furthermore, if the gradient of the ray is a rational number, written as an irreducible fraction, then you can quickly see that this ray must intersect a lattice point, as you can take several steps along the plane equal to the denominator and therefore travel up the plane several steps equal to the numerator. There- fore, it is evident that the ray will intersect a lattice point because it travels in integer steps (refer to the blue line in Figure 2).

Lastly, if the gradient of the ray is irrational — that is, it cannot be written as an irreducible fraction — the line can never intersect a lattice point. This makes sense, as to go up one step on the plane, you need to go an irrational step to the right; therefore, you can never land on a lattice point (see the red line in Figure 2).

In essence, we can see that our question can be rewritten. To solve our original problem, we need to find the probability that two numbers are coprime.

2 The Probability Two Numbers are Coprime

What does it mean for two numbers to be coprime? If two numbers are coprime, it means that the largest factor that the two numbers share is 1. Therefore, if you take the ratio of the two numbers, it is an irreducible fraction.

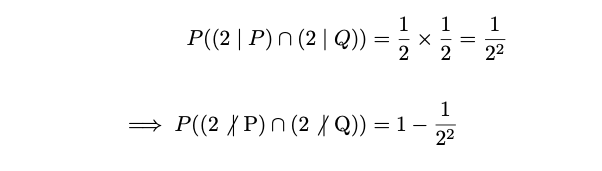

Consider two random numbers, P and Q, and their factors. What is the probability that P and Q do not share a factor of 2? Well, if we consider the natural numbers, every second number is a multiple of 2, so it can be deduced that the probability of a number being divisible by 2 is 1/2. Therefore, as the probability that P and Q have a particular factor is independent:

Now consider the probability that P and Q do not share a factor of 3. Every third natural number is a multiple of 3, so we can assume that the probability of a number being divisible by 3 is 1/3. Therefore:

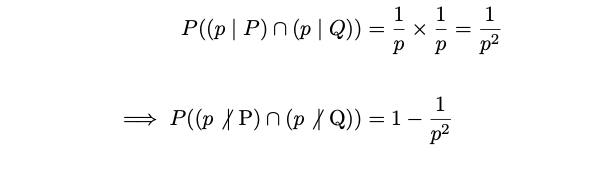

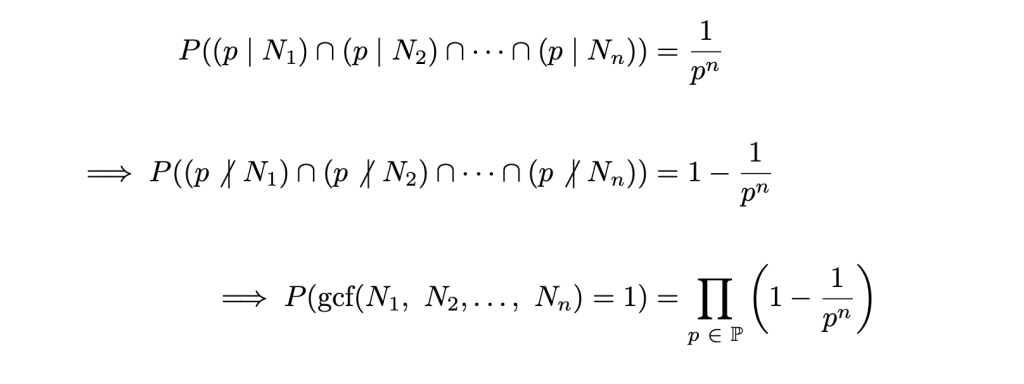

Repeating the process further, you arrive at familiar results, and so we can begin to notice a pattern: for every prime, p:

We want the chance that P and Q are coprime, meaning they share no factors. If two numbers are coprime, then it means that their greatest common factor (gcf) is 1; we can say:

How exciting! We have just calculated an infinite product to determine the desired probability. Now, we just need to evaluate the product. But first, before we move away from this formula for now, I believe it would be interesting to explore some of the history behind this product.

This product is interesting because it resembles the Euler product formula for the Riemann Zeta function.

The above equation was derived by Leonhard Euler in 1737 in his thesis Variae observationes circa series infinitas, where he develops the field of ana- lytic number theory and makes groundbreaking contributions to the study of infinite series.

2.1 Proof of Euler’s Product Formula

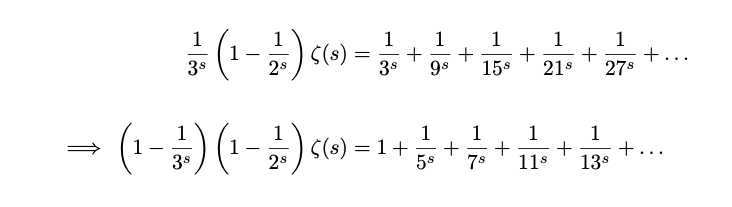

The proof of Euler’s product formula is concise, elegant, and crucial when evaluating the product in the future. The proof is as follows:

If we multiply this series by 1/2s , and subtract it from the original sum, an interesting result emerges.

What we can notice is that all of the fractions whose denominator had a factor of 2, have all been cancelled from the sum. If we now repeat the procedure for the next prime, 3, we can see similar results.

Now, the fractions whose denominator has a factor of 2 or a factor of 3 have all been cancelled from the sum. We can continue this process in a similar fashion for the rest of the primes. This cancels the sum until only a 1 remains, as shown below.

Not only is this proof elegant and easy to follow, but its result is exceedingly useful. Notably, Bernhard Riemann used this product formula in his ground- breaking 1859 paper Über die Anzahl der Primzahlen unter einer gegebenen Grösse , where Riemann extended the domain of the zeta function into the complex plane and studied its zeroes. Riemann also deduced that the zeroes of the zeta function determine the distribution of the prime numbers.

3 Solving the Basel problem

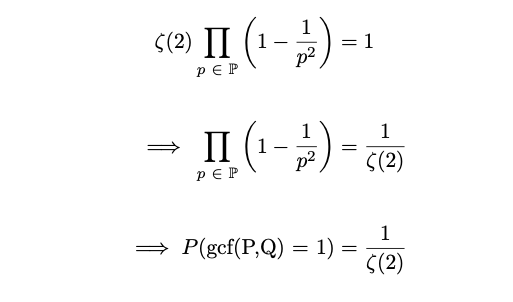

To recap what we have derived thus far, we have:

The problem remains to compute the probability that P and Q are coprime. If we consider ζ(2), we can notice something useful:

This is an incredibly useful result, as ζ(2) is a value that we can derive; in fact, Euler yet again has provided a solution for this problem.

3.1 Euler’s solution

First posed by Pietro Mengoli in 1650, what became known as the Basel problem was not solved until 1734 by Leonhard Euler. The problem, named after the home town of Euler, is to compute the sum of the reciprocals of squares or, in other words, to compute the value of ζ(2).

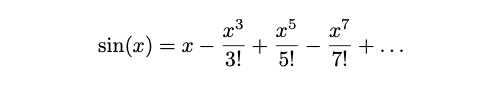

To begin Euler’s solution, we must first consider the Maclaurin series of sin(x).

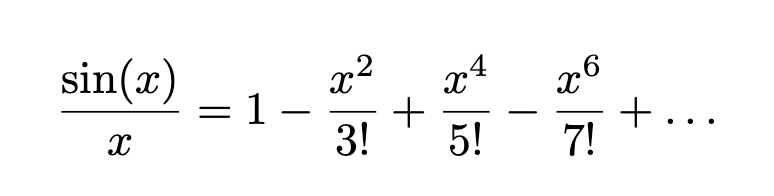

Now, dividing through by x attains the following series:

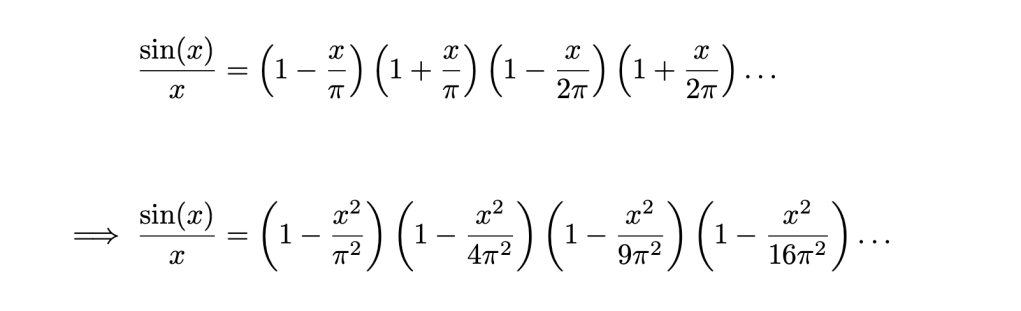

Consider the function f(x) = sin(x)/x (see Figure 3). If we consider the roots of f(x), we can begin to form a polynomial approximation for f(x). This is called the Weierstrass factorisation theorem, which shows that any entire function can be represented by a product, involving the zeroes of the function.

If you expand this product and collect all of the x2 terms, we arrive at the following as the coefficient of x2:

However, we can also consider the original value of the coefficient of x2 from the Maclaurin series for sin(x)/x , which has a value of 1/3! or simply 1/6 . As these two values are both the coefficient of x2 for sin(x)/x , they must be equal, so therefore we can equate them and solve as follows:

We finally have everything that we need to solve our original problem. Recall:

Finally, as the probability of two numbers being coprime is 6/π2, the probability of a ray extending from the origin and meeting a lattice point is also 6/π2, thus answering the original question that we posed at the start.

4 The nth dimensional game

Having computed the probability of a ray intersecting a lattice point with coprime x and y coordinates for a 2D plane, it is only natural to wonder how this probability may change as you extend this game into the 3D world. Now, instead of computing the probability that 2 random numbers are coprime, we must compute the probability that 3 random numbers are coprime. How can we do this? We can simply follow the same procedure as before!

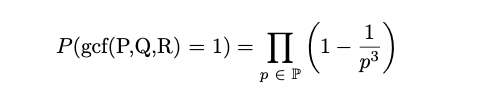

Consider 3 random numbers: P, Q, and R. Using the results previously derived in Section 2, it can quickly be shown that:

Following this, we can also find a form for the probability that P, Q, and R are coprime.

Considering ζ(3), we can quickly see that the probability of 3 random numbers being coprime is as follows:

Finally, we can see that the probability that a ray intersects a lattice point with coprime coordinates in a 3D space is 1/ζ(3) . Unfortunately, ζ(3) does not have a closed form solution, and can only be approximated using the expansions referenced above. Interstingly, ζ(3) is named Apéry’s constant after Roger Apéry, who in 1978 proved that it is irrational.

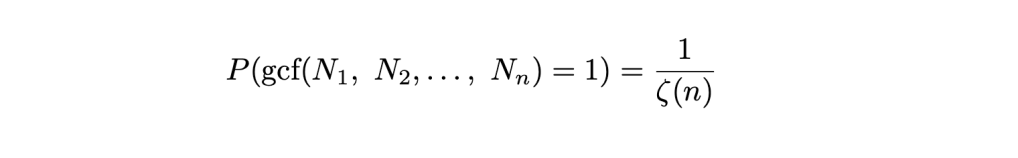

Knowing that for a 2D and 3D version of our game, we arrive at probabilities of 1/ζ(2) and 1/ζ(3) respectively, can we conclude that this pattern follows into higher dimensions? In fact, we can. If we simply repeat the above procedure, in the same way that we did for the 3rd dimension, for the nth dimension, we can arrive at a general formula for the probability that n random numbers are coprime.

Consider n random numbers N1, N2,…, Nn and their factors:

Finally, after considering ζ(n), we can finally arrive at our desired formula:

5 Conclusion

To summarise, extending our original game to the nth dimension has given way to a general formula for the probability that n random numbers are coprime. It really is remarkable how a seemingly complex problem can resolve into such a simple general solution; that is what I personally find most beautiful about mathematics.

This problem has been particularly entertaining to solve, as it requires you to think outside of the scope of the original question, and branch out to different areas of mathematics. Number theory is always an interesting topic, and it is especially fun to work with prime numbers and their properties. I thank you, the reader, for reading my essay and I hope that you have enjoyed this journey as much as I have.

[…] A Tangent about Tangents – Amelia Tan Coprime by chance: Probability to ζ(n) – John Winmill-Briggs […]

LikeLike