Akis Androulakis

One of the cornerstones of modern mathematics is the notion of a limit – maybe you’ve heard of them? Limits are centred around the idea of “arbitrarily close” or “approximating to an arbitrary extent”. To give an example, consider a real-life scenario in which a car drives for 10 minutes along a 10km route. Suppose that we want to measure its speed exactly 5 minutes into the route. A rather inaccurate estimate can be obtained if we divide the total distance of the route 10km, by the 10 minutes it took the car to complete it, obtaining the overall mean speed of 1km/minute or 60 kmph. However, a better estimate would be the mean speed of the car in the time interval from the 4th to the 6th minute. And an even better one would be the mean speed of the 10-second interval (4:55 – 5:05) and so on. Essentially, the approximation gets closer to the true value as the interval over which we are taking the average gets smaller. By considering smaller and smaller intervals we can continuously improve our estimate and doing so to an arbitrarily small extent is what happens when we take a limit.

This first article of the series will develop the main theory of limits and provide some examples, whilst the second and third articles will be increasingly more focused on applications.

Our first step towards understanding limits involves working with sequences: infinite lists of numbers in which repetitions are allowed and order matters. The nth term is usually denoted as aₙ and the sequence as (aₙ).

Eg: 1, ½, ⅓, ¼, ⅕, ⅙, … In this case, aₙ = 1/n for all n since for example, the 3rd term is ⅓, the 4th term ¼ etc.

Sometimes the terms of a sequence constantly approach a specific value. For example take the sequence: (aₙ) = (n + 1/n)

2 , 3/2 , 4/3 , 5/4 , 6/5 , 7/6 , 8/7 , 9/8 , 10/9 , …

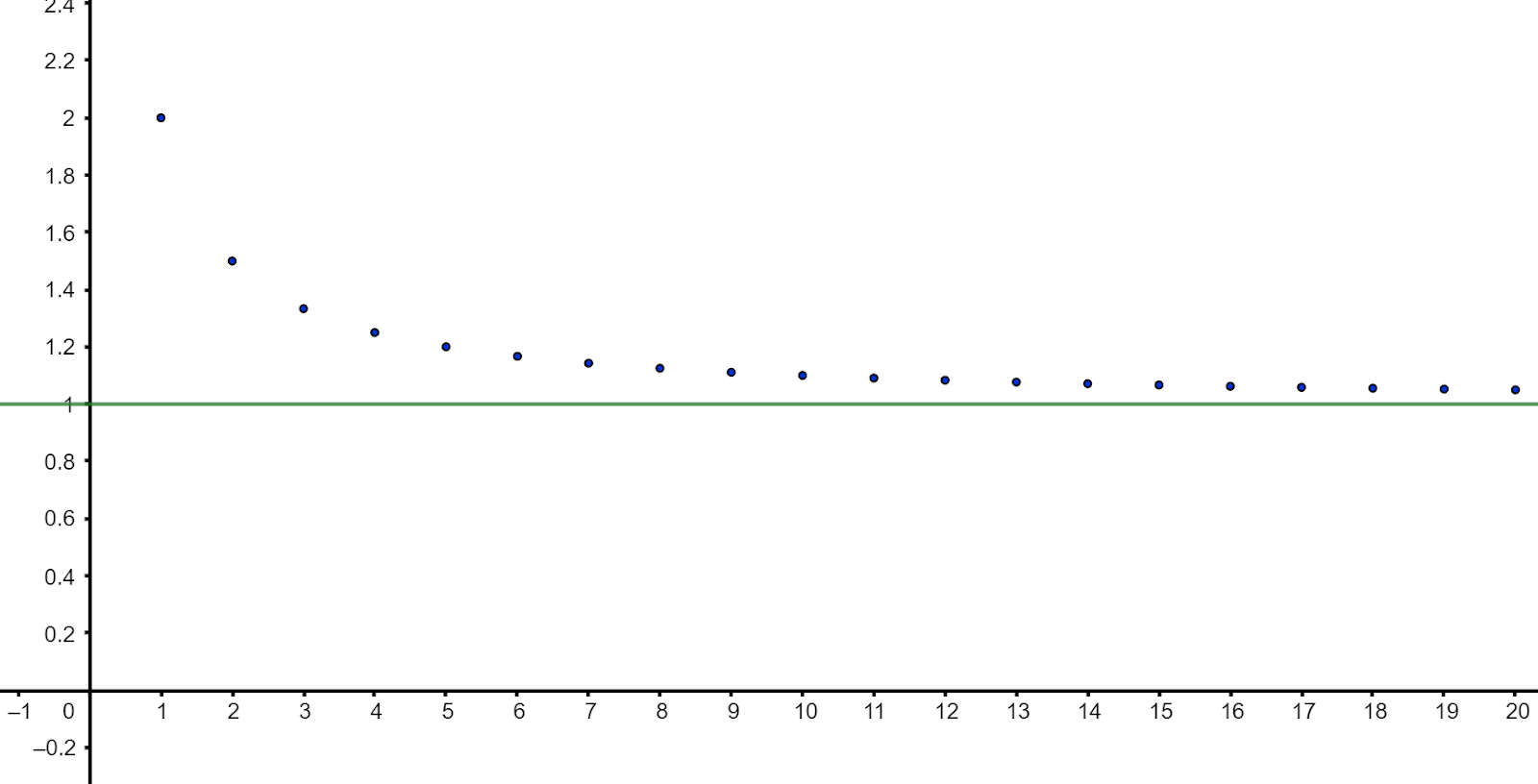

Looking at a plot of the successive terms below we notice that as we move further along the sequence the value of each term gets continuously closer to 1.

This intuitive idea is mathematically expressed in the following statement which we will refer to as (*) :

A sequence (aₙ) converges to a number x, which is called it’s limit, if:

For any positive quantity d, there exists some term (aₖ) in the sequence such that all subsequent terms will be within d of x.

This essentially means that after some point in the sequence all terms must be between x-d and x+d.

Let’s use the previous sequence as an example:

We claimed that (aₙ) = (n + 1/n) converges to 1 so we set the limit as x = 1.

To get a grasp of the concept, we will first check that the condition in (*) holds for d = 0.2 and d = 0.01

d = 0.2: we need to verify that after some term term aₖ, all the subsequent ones lie between 0.8 and 1.2

Looking at the plot we can see that indeed this is true after the fifth term a₅ = 1.2.

Note that a plot, although helpful, doesn’t constitute a proof because we can’t know if the graphical patterns we spot continue indefinitely. Instead, by realising that aₙ = 1 + 1/n , we see that all terms are greater than 1 and decreasing, since 1/n decreases as n increases.

Hence, for all n > 5: 0.8 < 1 < aₙ < a₅ = 1.2

For d = 0.01, the terms must lie between 1 – d = 0.99 and 1 + d = 1.01.

This time it takes 100 terms until the condition is satisfied. Using the same argument we deduce that for all n > 100: 0.99 < 1 < aₙ < a₁₀₀ = 1.01.

Observe that for a smaller measure of closeness d, the respective term aₖ lies further along the sequence (a₁₀₀ vs a₅). It is generally the case that aₖ depends on d as k represents the number of terms after which all subsequent ones will be within d of the limit. To establish convergence however, it’s insufficient to check the condition for a few values of d. Limits are about “arbitrary approximation”, which is why (*) requires that for any d > 0, no matter how small, the sequence eventually gets within d of the limit.

Which no doubt leaves you wondering, how can we check the condition for all values of d?

The idea is to consider an arbitrary d and find a suitable aₖ with respect to that arbitrary d (ie k will be a function of d). In practice:

Let d > 0, we look for a k such that for all n > k: 1 – d < aₙ < 1 + d

Previously for d = 0.2 and d = 0.01 we saw that k = 5 and k = 100. Now we continue with an arbitrary d and substitute into our inequality aₙ: 1 – d < 1 + 1/n < 1 + d

Simplifying (by removing the 1): -d < 1/n < d

As 1/n is positive, -d < 1/n holds for all n anyway, so re-stating our objective:

We look for a k such that for all n > k: 1/n < d, or equivalently n > 1/d.

Therefore, we just pick k to be the first whole number greater or equal than 1/d.

Summing up, for any d > 0, if we take k to be the first whole number ≥ 1/d, then all terms after aₖ will be within d of 1. We have thus officially proved that the sequence converges to 1.

Now that we have developed the necessary theory, it’s time to see a fun – and somewhat infamous – application.

We’ll show that: 0.9999… = 1.

To do that we’ll consider the sequence: (aₙ) = 1 – (10)-n

a₁ = 0.9 = 1 – 0.1

a₂ = 0.99 = 0.9 + 0.09 = 1 – 0.01

a₃ = 0.999 = 0.9 + 0.09 + 0.009 = 1 – 0.001

…

Therefore, we can see that the only sensible way to define 0.999… is as the limit of our sequence. Hence all we have to show is that the sequence converges to 1 by using the previous technique.

Let d > 0, we look for a k such that for all n > k:

1 – d < aₙ < 1 + d ⇔ 1 – d < 1 – (10)-n < 1 + d ⇔ -d < -(10)-n < d

but the right inequality always holds, so we look for k such that for all n > k:

d > (10)-n

If d ≥ 0.1 then take k = 1

if d < 0.1 then consider the decimal form of d and take k to be the number of 0’s shown before the leading digit (eg: for 0.004 choose k = 3).

This is not, strictly speaking, a formula but instead more like a procedure of finding k for every possible d, however, this is more than enough! In fact, (*) requires the existence of such a k for each d, not a formula. That is, we don’t need to specify when the terms of the sequence will be within d of the limit (which is what k represents), we just have to verify that they will eventually be (which is what the existence of k guarantees). Hence the limit is 1.

A key idea in this proof that is used very frequently in mathematics is to express a complex mathematical object as the limit of a sequence of simpler objects with known properties. We did this above by expressing the decimal expansion of 9’s in terms of the number 1 and subtracting increasingly small powers of 10.

For another example from geometry, one of the first derivations of the formula for the area of a circle exploits that the area is the limit of a sequence of areas of inscribed regular polygons. This idea is shown by the figure below.

This introduction of limits may have seemed rather formal compared to the intuitive concept of a limit, and the initial example at the beginning of the article. Indeed the reason behind the careful treatment of limits is that, as will be thoroughly demonstrated in the next article, our intuition in even slightly more complex scenarios is usually wrong…

Article 2: Puzzling Limits

[…] the first article we introduced the concept of a limit and saw some examples of how it can be used in calculations. […]

LikeLike

[…] dedicating two articles to the underlying theory of limits and to relatively abstract examples, it’s time to shift our focus to some real-life applications. […]

LikeLike