Yu Xiao

What do you think of when you hear the word proof? Lots of numbers? Maths symbols? Equations? Whilst this may be true of your lessons at school, it need not always be the case. It turns out that some complicated maths theorems can be “proved” without any equations or even words! Visual proofs employ straightforward diagrams to summarise all the information contained in several paragraphs, and give us further insight into the essence of the problem. For example, can you see the connection between squares, dominoes, and the Fibonacci numbers 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, … ?

Let’s start by casually playing with some squares and dominoes. Suppose we have a board of length n and two types of tiles: squares, with length 1, and dominoes, with length 2 (the width of all tiles is fixed at 1). Let’s consider how many different ways there are to tile the whole board with squares and dominoes. When n = 1, there is only one way to tile the board, namely with 1 square. When n = 2, there are two ways: with 2 squares or 1 domino. If we do more calculations, we will get the following sequence:

Wait a minute… 1, 2, 3, 5, 8 are the Fibonacci numbers! Fibonacci numbers refer to numbers in the sequence (Fn) = {1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21…}, where we obtain the next term by adding the previous two terms. This simple sequence appears everywhere in our daily life: the number of petals of a flower, the curve of the Nautilus shell, and the golden ratio. (If you want to know more, there are many online articles and videos about the significance of Fibonacci numbers in nature.) And wow we have another application of the Fibonacci numbers to real life: the number of possible tilings with squares and dominoes.

But be careful, even though we can find some connections between abstract mathematical concepts and practical objects, it’s still important to prove the formulae with strict logic. We’ve shown that the number of tilings of a board of length n = 1 to n = 5 coincides with the Fibonacci numbers, but what about longer boards? Let’s call a board of length n, an n-board, and denote fn to be the number of tilings of an n-board with squares and dominoes. Recall that every Fibonacci number is the sum of the previous two, which in mathematical terms gives: fn+1 = fn + fn-1 for n > 0. We can verify that this works for small values of n since we know the first few terms of the sequence are 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, … which all fit the pattern: adding the previous two numbers gives the next one. However, when n is large, it’s impossible to list and count all the tilings by hand, which means we need a proof.

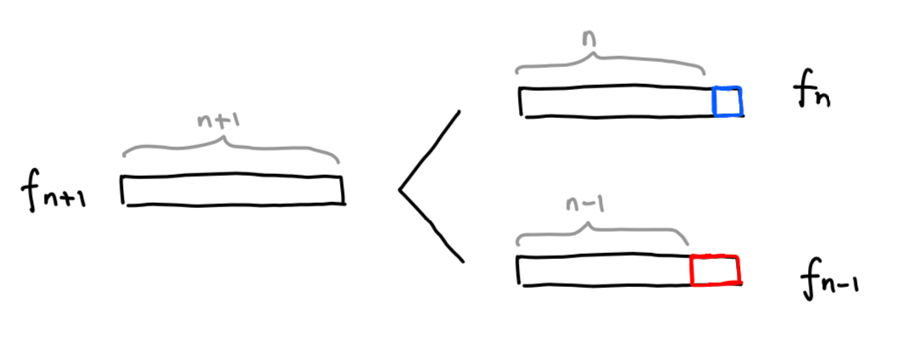

Let’s consider an (n+1)-board. By definition, there are fn+1 ways to tile this board. We start by thinking about the last tile. If it’s a square, then the remaining board has length n, and there are fn tilings of this shorter board. If the last tile is a domino, then the remaining board has length n-1, with fn-1 possible tilings. Adding the two possible cases together, we see the number of ways to tile the (n+1)-board is also fn + fn-1 and thus the formula holds true. Since this is true for any value of n, the proof is complete.

We may now claim that the (n+1)th Fibonacci number is the number of ways to tile a board of length n with squares and dominoes, as we have proven it with diagrams as well as strict logic.

In fact, we can go forward to prove many more formulae with this powerful visual interpretation. For example, we can show that the sum of the first n Fibonacci numbers is: f0 + f1 + f2 + … + fn +1 = fn+2. Here we define f0 = 1 to represent the only one way to tile a board of length 0, that is with 0 squares and 0 dominoes.

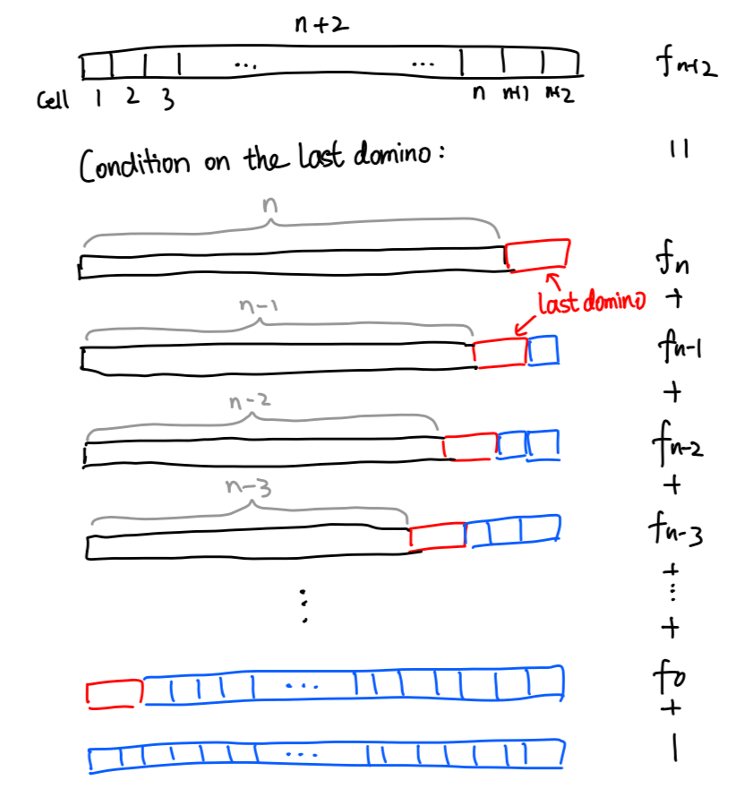

Consider an (n+2)-board. Let’s number the cells of this board from 1 to n+2, as shown in Figure 4. We begin by considering the position of the last domino: if the last domino covers cell n+1 and n+2, then the remaining board will have length n, so there are fn tilings. If the last domino covers cell n and n+1, and a square covers cell n+2, then the remaining board on the left will have length n-1 with fn-1 tilings. If we keep moving the last domino to the left (as shown in the figure), until the last domino placed covers cell 1 and 2, and all the other cells are covered by squares, then with a little thought, we can deduce that there are f0 = 1 tilings of this kind. Adding all of the cases together we get f0 + f1 + … + fn, as shown in the figure, but where does the +1 come from? Don’t forget that there is also a case where there is no “last domino”: the whole (n+2)-board can be tiled only with n+2 squares. This is the one case we are missing, so finally we have f0 + f1 + … + fn + 1 = fn+2 and the proof is complete.

So there you have it! Just by playing with squares and dominoes, we’ve proven two formulae. And it doesn’t stop there. There are many more things we can do, like cutting the board in the middle, swapping the tails, or even connecting both ends of the board to make a bracelet… A visual interpretation turns abstract mathematical concepts into practical things that we can play with, and each practical operation in turn corresponds to a beautiful mathematical formula. Playtime continues in the next article where we derive even more beautiful formulae using nothing more than squares and dominoes – see you there!

References:

- Proofs that Really Count by Arthur T. Benjamin and Jennifer J. Quinn.

- https://mathimages.swarthmore.edu/index.php/Fibonacci_Numbers.

[…] the previous article “Maths Proofs Without Words” we introduced the visual interpretation of the Fibonacci numbers: the (n+1)th Fibonacci number […]

LikeLike

[…] the previous two articles, we’ve talked about how the Fibonacci numbers represent the number of ways to tile a board with squares and dominoes, and how we may explain interesting Fibonacci properties using visual proofs. In fact, there are […]

LikeLike