James Somper

Chaos Causing Considerable Confusion Clarifying Changes Concerning Clouds: How Chaos Complicates Weather Forecasting

Weather forecasting. We all love to hate it. It’s forever a topic of conversation, and many jokes are made at its expense. The main complaint being how inaccurate it often appears to be. Think about the number of times you’ve seen an article purporting that next week, some weather front or another is going to cause extreme heat / cold (delete as applicable) and that the UK is going to suffer due to tarmac melting / everything freezing (delete as applicable). Now think about the number of times this predicted weather has materialised, and you will rapidly realise that weather forecasting can often appear to be anything but an exact science. So why is our ability to predict the elements so poor, and will it ever get any better? To answer this, we first have to take a look at the history of weather forecasting.

Weather forecasting is doing exactly what it says on the tin. Through it, one attempts to forecast the weather, be that the weather in an hour, a day, a week, a month, or any other amount of time in the future. People have been attempting to predict the weather for millennia informally, through rules of thumb. Some of these are so popular that they have made it into common parlance such as “red sky at night, shepherd’s delight, red sky at morning, shepherd’s warning”, which is to say a beautiful red sunset means no rain the following day, whilst a beautiful red sunrise means the day is likely to be a wet one.

Weather forecasting has been done formally since the 19th century, and the methods for doing it have evolved over the years. Originally, weather forecasts were drawn up by manual calculation of changes in air pressure, as well as altering the result based on sky condition, the current weather (if your forecast predicts glorious sunshine in the next 10 minutes, but it’s pouring with rain, you’re probably right to discard the forecast), and cloud cover. It wasn’t until the 20th century that the maths really came into its own, with Lewis Fry Richardson publishing his work “Weather Prediction by Numerical Processes”. He described how small terms in the fluid dynamic equations that describe the flow of the atmosphere could be neglected, and so a scheme could be drawn up to have a numerical method for solving these equations. He envisioned a room filled with thousands of people performing these calculations. This was, rightly so, considered silly. However, a machine was rising to prominence that excelled in completing many calculations, far faster than a human ever could. That machine was the computer, and with its help, the first numerical predictions for weather began to be accessible.

Hence, the problem of weather forecasting was solved in the 1950s, and we have never had an issue with predicting the weather since. Or at least, that would have been a nice conclusion to the story of weather forecasting. Unfortunately, the equations that dictate weather processes, such as the flow of fluids in the atmosphere, are inherently chaotic. Because of this, it becomes incredibly difficult to accurately predict what the system (and hence what the weather) will be. Furthermore, the fact that the equations also cannot be solved analytically renders us slaves to numerical methods, and this limits our ability to accurately predict weather further. But what does it mean to not be able to solve something “analytically”?

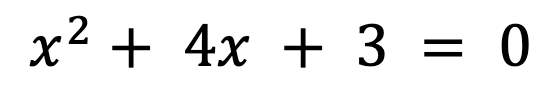

Analytically, in mathematics, means “without just brute forcing the answer with numbers”. For example, the equation:

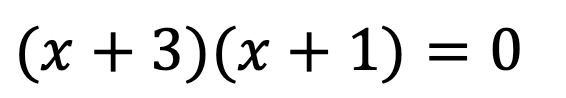

can be solved “analytically”, which is to say, through mathematical analysis. We can factorise the equation to:

and so, we see that the solutions are x = -3 and x = -1. There was, in fact, no reason that we had to do this analytically. We could have instead just tried trial solutions until we found answers that worked. This would be considered a “numerical method” for solving the above equation. So, given the ‘trial and error’ approach of numerical methods, you may ask why we would ever want to resort to solving something numerically? There are two main reasons:

1. We just can’t solve it analytically

Mathematicians have limits. There are a limited number of things that can be done in order to attempt to solve equations, which means that sometimes, there simply doesn’t exist a way to proceed to a solution. This situation occurs in many physical systems, including the description of atoms and molecules. The operator above describes the electron-only portion of an equation that describes the motion of electrons in a helium atom. It does not include the movement of the nucleus, so this model is already an approximation. However, the above equation cannot be solved analytically. We are unable to find a solution using just the maths that we know. We therefore have to resort to numerical methods in order to describe helium atoms (and actually, all atoms above hydrogen).

2. It would take too long to solve it analytically

Sometimes, we care more about getting an answer quickly, and less about how accurate that answer is. If we had a model that would exactly predict tomorrow’s weather, but in order to compute this exact model, it would take more than 24 hours, then the model is useless, as it tells us information no faster than we can find it out by ourselves. These situations arise often when dealing with massive amounts of data and calculations, and so to get around this problem, we resort to making approximations, and using numerical methods to approximately solve our equations. This may not give us an exact answer, but if the exact answer takes too long, then an approximately correct answer is often seen as better.

As the equations that dictate weather cannot be solved analytically, this means that large amounts of computing power are needed to numerically solve the equations instead. Even once that is done, a human is still required to check that the solution makes sense, and this human must be well-versed in these methods in order to be able to discern what is real data, and what is machine bias.

This is compounded with the chaotic nature of the system. These equations take data not only from around the country, but from around the globe. Our overarching theme of chaos is that small changes in input will lead to large, unpredictable changes in the output. This means that if these inputs are even minutely wrong, the calculated system could look wildly different from the true nature of the system in a week’s time. These inputs will always be somewhat wrong, as this data must be measured by instruments which have a defined sensitivity – which means they can only record data to so many decimal places – and so there is always some minute error. Therein lies the reason for why weather forecasting can get the answer so very wrong. So, is there anything we can do about this?

The answer is a resounding yes! Although weather forecasting in the medium timescales (such as 2 weeks to 3 months ahead) has remained very difficult, we have systems that are able to predict with relatively high accuracy what the weather will be in the next 5 days, and what the weather will be in the next 5 years. Why is that? It comes from how approximations are made in order to deal with chaotic systems. A method of averages is often used to allow problems to be simplified, and hence give generally good answers at the start of the approximation, as any errors have not had time to propagate yet. It also gives us a good idea of what the system looks like in the very long term, as generally, all the effects average out, and so over a long time period we can use a method of average values to accurately predict what the system will look like. However, in the middle, we have chaos, utter and complete chaos, as our assumption that every point in our system has an average value is false, and as the small variations lead to large changes in output due to the system being chaotic. In the middle, we simply cannot predict very accurately what the system will look like.

To consider this, envision the following game. You start with 100 points. Each day, I add a value to your points ranging from -2 to + 5, with all these values having equal probability of occurring over the span of the game. In this game, the 100 points are the current weather, and the values I add or subtract are the changes in the weather. The final rule of the game is that I remove up to five of these possible numbers (-2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) depending on how close the change is. That is to say, if you are trying to guess what the change will be tomorrow, there will only be two numbers it could be, but if you are trying to guess what the change will be in a week’s time, it could be any of the 8 values. In other words, the number of values it could possibly be gets smaller the closer that date becomes. If we tabulate and explore this game, assuming we start on a Monday, we have the following result for the first day.

| DAY | POINTS | POSSIBLE CHANGE TOMORROW | POSSIBLE POINT VALUES TOMORROW |

| Monday | 100 | -2, +3 | 98, 103 |

| Tuesday | -1, +5, 0 | 97, 102, 98, 103, 108 | |

| Wednesday | -2, 0, 1, 4 | 95, 100, 96, 101, 106, 97, 102, 98, 103, 108, 99, 104, 109, 106, 112, 107 | |

| Thursday | -2, -1, 3, 4, 5 | Many values | |

| Friday | -2, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 | Even more values | |

| Saturday | -2, -1, 0, 2, 3, 4, 5 | I’m not listing these | |

| Sunday | -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | There’s just too many |

As we can see, we can be relatively sure about the result tomorrow, and even the result the following day, but by the time we have reached Thursday, we have very little idea of what the value of our points will be. However, if we play the game forward a day (and assume that we added 3 to our points), suddenly our new table looks like the following:

| DAY | POINTS | POSSIBLE CHANGE TOMORROW | POSSIBLE POINT VALUES TOMORROW |

| Monday | 100 | N/A | N/A |

| Tuesday | 103 | -1, +5 | 102, 108 |

| Wednesday | -2, 0, 4 | 100, 106, 102, 108, 112 | |

| Thursday | -1, 3, 4, 5 | Many values | |

| Friday | -2, 0, 1, 3, 4 | Even more values | |

| Saturday | -2, -1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | I’m not listing these | |

| Sunday | -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 | There’s just too many |

We notice a few things about our new system:

- We have narrowed down with greater accuracy what will happen on Tuesday, as compared to last time – we now have only two options instead of five.

- We have narrowed down with greater accuracy what will happen on Wednesday, as we now have 5 values instead of 16.

And most importantly for this analogy:

- Some of our predicted values for Wednesday and Thursday have now disappeared.

This statement is equivalent to us “getting the forecast wrong”, because if someone asked us on Monday what the points on Wednesday were going to be, we could have said “well it might be as low as 97”, but now, we would have to come back and tell them “no, sorry, got that wrong, it will either be 102 or 108 on Wednesday”, which means we could effectively be out by over 10 points.

The final observation we can make about our game is that we can predict what will happen in the long term, in the same way I claimed earlier about the weather. Since we know that all the values are equally likely, we can take the average expected value for a day, which is the mean of our values. This gives an average daily increase of around 1.5 per day, and so if someone asks us “in thirty days, what will the points be?”, we can tell them “around 145” and we are unlikely to be too far out.

This game parallels weather forecasting, at least in some regard. It demonstrates how in the short term, we can be relatively sure of what will happen, but in relatively short amounts of time ahead of this, we can’t be sure what will happen at all, even though we can predict the overall change that will happen to the system in the long term. And this of course is all without considering that weather is controlled by a plethora of far more complicated systems than just adding or subtracting a number, and so the complexity of weather prediction skyrockets. As computers get better and better, the amount of calculations we will be able to do will improve, and so we will slowly get better and better weather forecasts, but for the time being, the models we have are about as good as it gets.

So, next time the forecast gets the weather a little wrong, or even massively wrong, perhaps don’t immediately scoff, or make a well-placed joke at the forecaster’s expense. Instead, marvel at the fact that they were able to give you even a vague answer at all!

Next time, we will explore our final example of chaos in nature, and we will be turning our eyes to the stars – read it here.

[…] the next article, we will explore weather forecasting in more detail, and try to answer the forever-asked question […]

LikeLike

[…] fact, it is indeed weather forecasting all over again, as the solar system is another example of a chaotic system, which brings with it all the […]

LikeLike