A huge congratulations to Flynn Nugent for their essay on ‘Clepsydras, Toricelli’s Law and Gabriel’s Horn’ which has been awarded first prize in the adult (over-18) category for the 2024 Tom Rocks Maths Essay Competition.

“It’s informative, entertaining, and has just the right balance of complex mathematics, mixed with intuitive explanations and visualisations. The fact that we go from the historical example of using flow rates to measure time consistently with clepsydras, through to emptying infinitely long objects filled with a finite amount of fluid, with such continuity in the writing, is a testament to the author. The maths covers a wide range of topics, all of which are well-explained, and leaves the reader with an overall sense of wonder as to what other hypothetical objects can be analysed using the tools of mathematics.”

Flynn’s essay will be published on the university website, and they will receive a free place on one of the Department for Continuing Education online WOW courses – the full list of which can be found here: https://www.conted.ox.ac.uk/about/weekly-oxford-worldwide

Here is the essay in full – enjoy!

Clepsydras, Torricelli’s Law and Gabriel’s Horn

1 Introduction

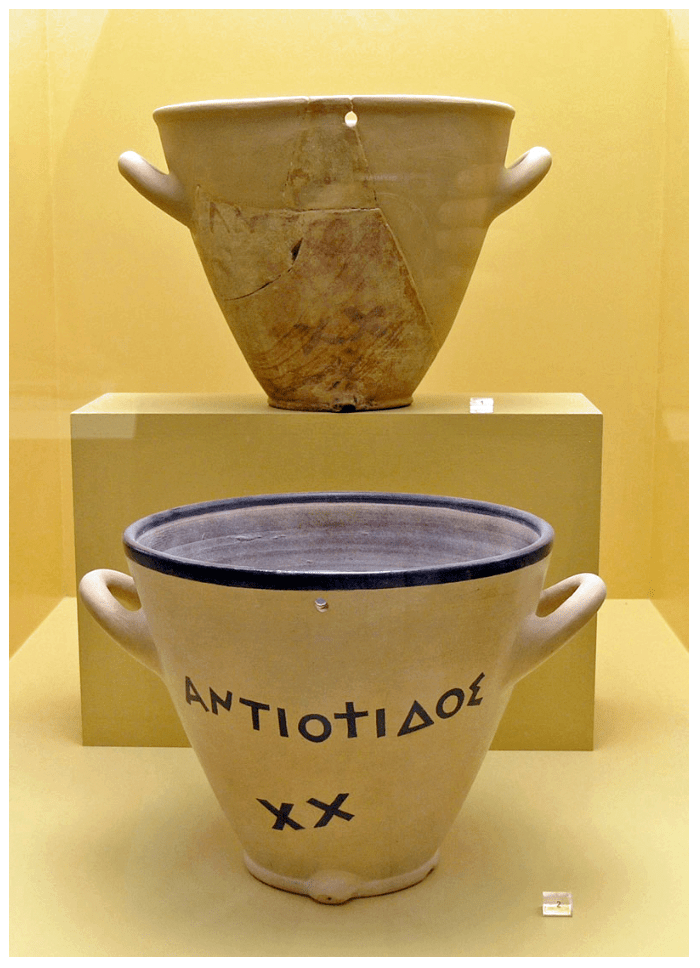

The concept of keeping time by letting water flow out of a container has been around since antiquity, in ancient Greece water clocks called clepsydras were used as a way to keep time. They were used in Athenian courts to keep track of speaking time for both the plaintiff and defendant [1]. So what did this device consist of? Two containers, one above the other, a hole in the top container and water which flowed between them, such a simple and reliable system.

Later editions of the clepsydra, as developed by Ctesibius, had systems which kept the top container at a constant fluid level to overcome the issue of diminished flow [2].

Physics has moved on significantly since ancient Greece and we now have equations which can be used to calculate the flow characteristics of water clocks with various shapes of containers.

This essay will look at the mathematics behind emptying containers with holes in the bottom, we will also look at how an equation to calculate the time it takes for an arbitrary container to empty can be derived. We will look at an application of this equation. Finally we will look at an interesting case; what happens when you apply the equation to Gabriel’s horn and an explanation for the result.

2 How can we simplify a fluid?

Fluids are complex and if we don’t make assumptions to simplify them they will be impossible to model with current mathematics. The first assumption we will make is that the fluid is incompressible. This means we can model the fluid density as being constant, this is a good assumption. If you take a plastic syringe, fill it with water, cover the hole at the end and then try and push down the plunger you will notice that it doesn’t move. For water a pressure of 150 atmospheres will produce less than a 1 percent increase in density [3]. Fluids in this essay will be getting nowhere near that pressure.

We will then assume that the fluid is inviscid which means it has no viscosity. This is a good assumption because the holes will not be very long for mathematical purposes. We will assume the bottom of the container is lamina so there are no loses to friction as the fluid exits through the hole.

Lastly we will also model the flow as steady and laminar which means that the properties of the flow are the same at every point in the flow at any time

3 Equations we need to know

We need to know Torricelli’s law which is the equation which governs the velocity of the fluid exiting the bottom of a container filled with fluid to a height h:

This equation is derived from the Bernoulli equation. I will not derive Torricelli’s law as I don’t want this essay to be too long, however, here is a very enthusiastic physicist who will derive it instead [4].

We also need to know that the volume flow rate is given by the product of the velocity of the fluid flow and the area the fluid is flowing through:

We also need to know that for incompressible flow, which is being used in this essay, the volume flow rate is conserved at all points in the flow so for any pair of points, 1 and 2:

These equations explain why it was important for the fluid level in a clepsydra to remain constant as it was easier to keep time if the flow was consistent. The ancient Greeks didn’t have access to Torricelli’s Law, so they couldn’t accurately calibrate the clepsydras when the flow rate was inconsistent.

4 Deriving the general equation for emptying time

We need to find an expression for the time derivative of the height, this will give us a differential equation which we can then rearrange for time, we can look at the volume flow rate at two locations, the first is the hole in the bottom of the container has a radius of r. The area of the hole is πr2 then using Torricelli’s Law the velocity of the fluid will be √(2gh). Therefore the first expression for volume flow rate is:

We can also measure the volume flow rate inside the container. The height of the fluid will be decreasing at a rate of dh/dt, the velocity the fluid inside the container is moving at.

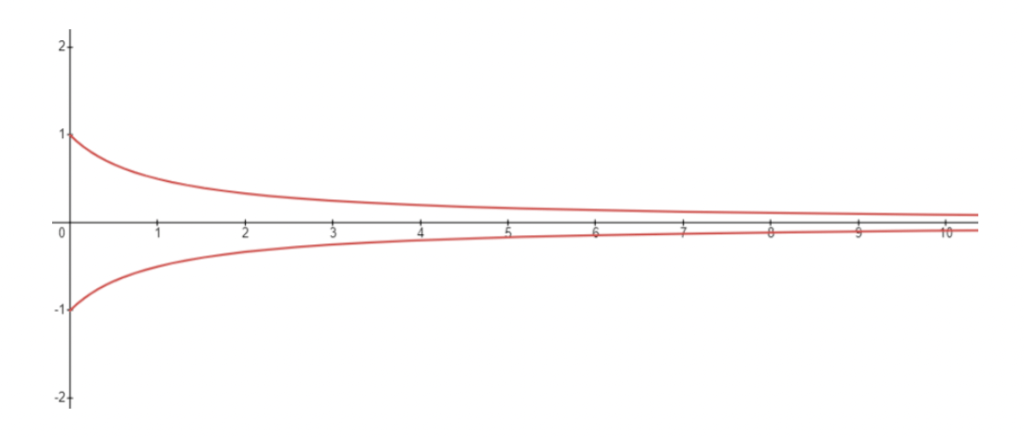

We need to figure out what to do with the area of the surface of the fluid. The radius of the container, and therefore the area of the surface of the fluid, may change with height, meaning we have to write the radius of the container as a function of the height of the container. We will call this R(h), which means the container is a volume of revolution of R(h) around the h-axis. Therefore the area of the surface of the fluid at height h is πR(h)2. We now get the second equation for volume flow rate:

Q2 is the rate the volume in the container is changing and Q1 is the rate the fluid is leaving the container. Since we are not adding fluid to the system, the sum of Q1 and Q2 must be 0.

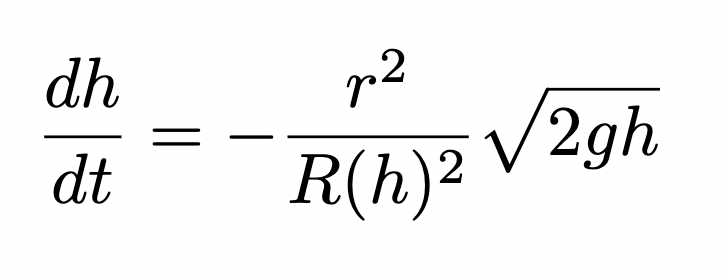

Rearranging for dh/dt gives us the differential equation for any container which is a volume of revolution of a function R(h):

We can write this by separating variables, remembering that R is a function of h.

Thinking about the limits of integration, the initial conditions will be that when t = 0 the container will be completely full to a height H0, and for the upper bound the container will be empty at time T, so h will be 0.

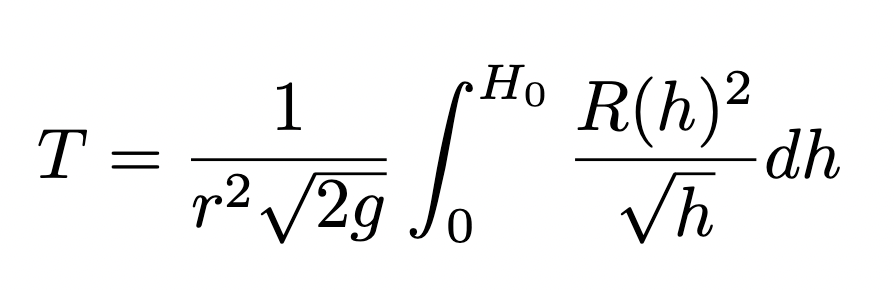

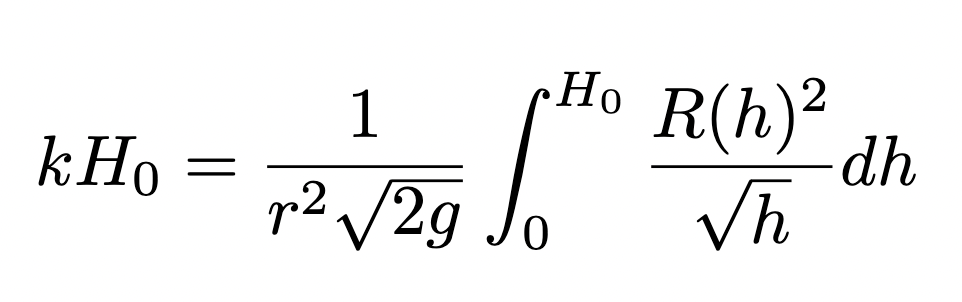

Finally dividing both sides by the constant values inside the right hand integral, and then evaluating the right hand integral, we obtain time elapsed as a function of height of the fluid. To simplify it fully we can get rid of the negative sign by swapping the limits of the integral:

We can now calculate the time it takes for many different shapes of container to empty, as long as the container is a volume of revolution of R(h). If the integral is non-elementary there are various numerical methods which can be used to get a very good approximation.

This equation can also be used in reverse to find the heights at which you need to apply demarcations for each unit of time on a water clock – if only the ancient Greeks knew about integration…

5 The lazy persons’ container

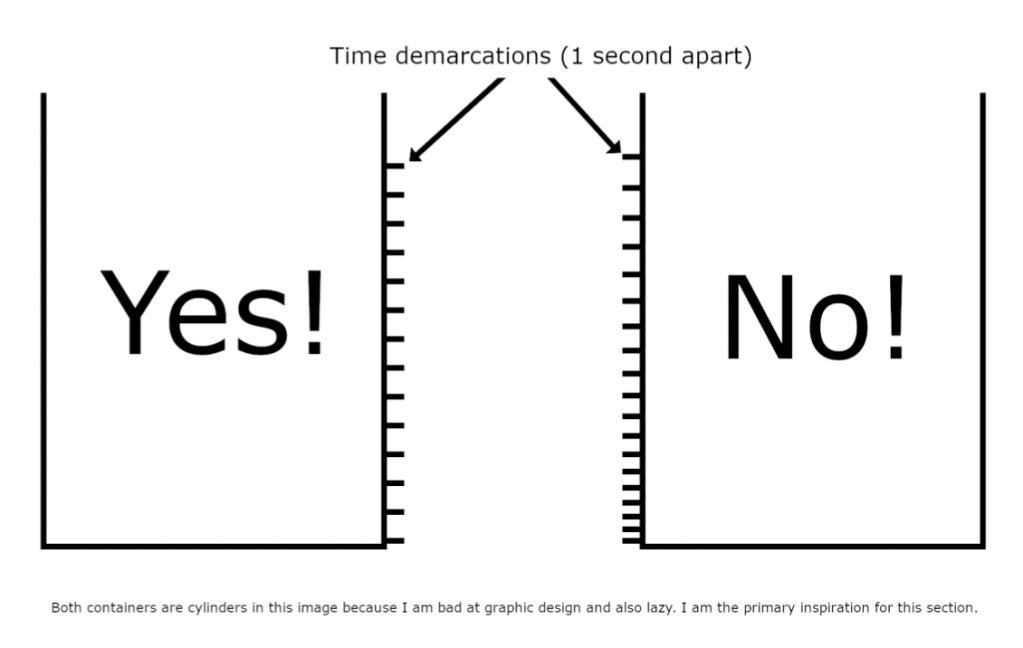

We are in charge of making a container for a clepsydra which needs demarcations at various heights. The distance between each demarcation should represent one second. We could make a cylindrical container, however, because the water will drain faster at the start of the emptying process, gradually slowing down until the container is empty, the demarcations at the top will be more spaced out than the demarcations at the bottom.

We are lazy and don’t want to have to deal with different spacing between demarcations, even with the mathematical tools we have now we would have to calculate the distance between every demarcation and the apply them to the container. That is too much work. We want to just do one calculation. So we are tasked with finding a shape for the container such that the spaces between the demarcations are all the same, as shown below.

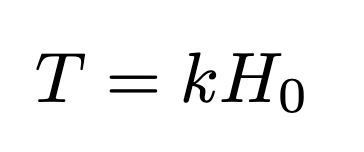

In order for this to be the case the height must decrease at a constant rate, and since time passes at a constant rate, the time taken to empty must be proportional to the initial height of the fluid.

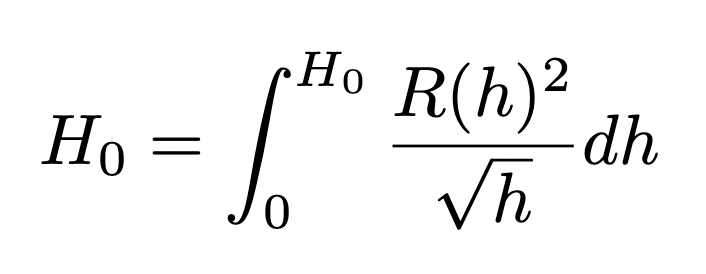

We derived an equation for T in the previous section so we can make that substitution, integrating from 0 to H0 as we are looking at the time taken for the container to empty.

Since we only want the general shape for the container we can remove the constant terms as they will only scale the shape.

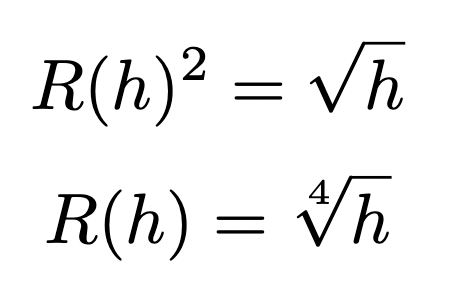

Ask yourself. The integral of what, with respect to h, gives h? Well that will be the integral of 1. Therefore if the integrand is 1.

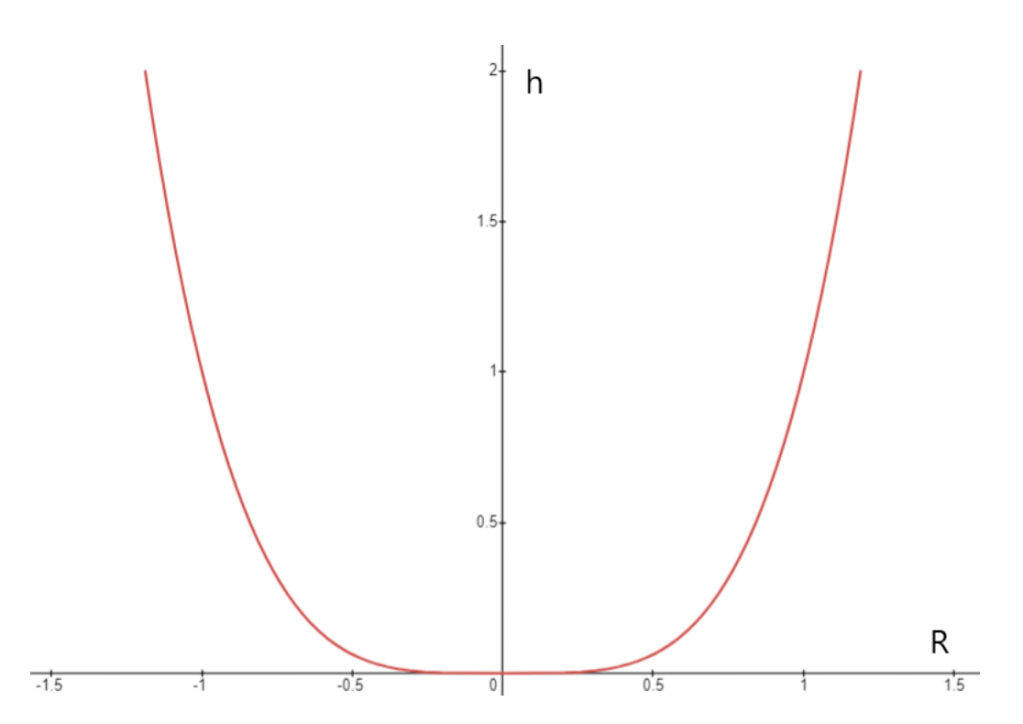

This tells us that the shape of the container should be the the function R(h) = h1/4 revolved around the h axis, in order for the time demarcations to be equally spaced. This makes our life a lot easier because we only have to do one calculation instead of dozens of calculations which would be the case if the container was any other shape.

If you look at the shape of the top container in a real clepsydra, it’s sort of a similar shape… I mean it’s not great but then, as I have mentioned, the ancient Greeks didn’t have access to Torricelli’s Law. They were still trying to figure out how shapes work.

6 What about something like Gabriel’s horn?

Gabriel’s Horn is a famous geometric shape, it has a finite volume but an infinite height. If we look at Torricelli’s law an infinite height would mean that if we put a hole in the bottom of Gabriel’s horn the fluid should exit at infinite velocity, so does this mean that Gabriel’s horn would empty immediately? You would think so, but I am going to show that is not the case.

Gabriel’s horn is the function of y(x) = 1/x for x ≥ 1 revolved around the x-axis. This means the volume of Gabriel’s horn is given by the following integral, which comes from volumes of revolution.

Which evaluates to:

We have confirmed that Gabriel’s horn does have a finite volume. Now, how long will it take to empty? Strap in for a rather long bit of maths. I will try and finesse the boring derivation with some comedic statements.

First, we will change the variables from x and y to h and R respectively.

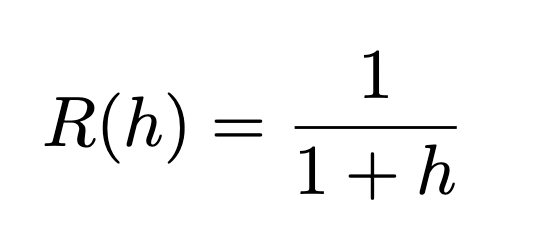

Second, we want to translate the graph such that the domain is h ≥ 0 rather than h≥1, because the hole in the bottom needs to be at h=0. This is a simple graph transformation, we add 1 to all the h-values before taking their reciprocal. This gives us:

Which looks like this (note that -R(h) is also graphed to show what the side profile of the container looks like) – it looks like one of those comically long fanfare horns [6].

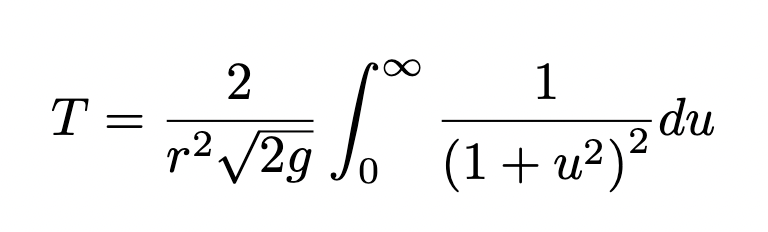

We now substitute R(h) into the integral we derived in section 3. We want to know how long it takes to go from being full to being empty. Therefore the upper limit of integration is ∞ and the lower limit is 0.

This integral doesn’t look very easy to solve – I definitely did not use wolfram alpha to get the solution – but it is completely solvable using integration by substitution. I don’t want this essay to go on forever so I will outline the substitutions and then give the resulting integral (perhaps this can be a small exercise to practice integration by substitution).

Firstly let u = √h. The integral becomes:

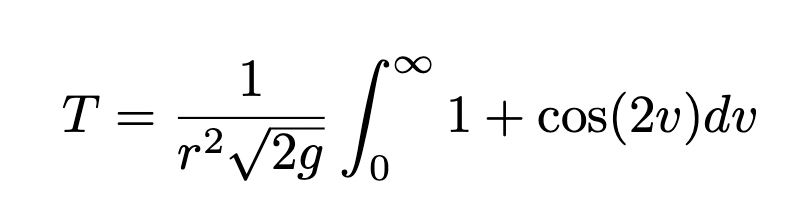

Now make a second substitution of u = tan(v). The integral now becomes:

It’s looks much simpler now, however, in maths looks can be deceiving. Just ask the people who have seen the integral of the square root of tan(x) [7]. Fortunately, this is nowhere near as difficult. We can solve this by simply rearranging the double angle formula for cos(2v)

Substituting this into the integral and taking the factor of a half outside the integral we get

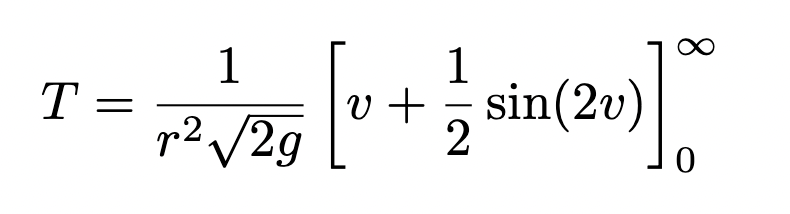

and we can integrate this quite easily. The integral of 1 will be v and the integral of cos(2v) will be 1/2 sin(2v).

This result looks nice, except we now have to back substitute to get an expression in terms of h, noting that u = tan(v) means that v = arctan(u). We get this ridiculous looking expression, but that’s ok because it simplifies quite nicely.

We can evaluate the limits: arctan(0) = 0 and sin(0) = 0. Therefore the lower limits can be ignored, but what about the upper limits?

Well, using the chain rule for limits, the limit of √h as h tends to infinity is infinity and the limit of arctan(h) as h tends to infinity is = π/2, so we can reduce to

Which means we get the final expression:

The time it takes for Gabriel’s Horn to empty according to Torricelli’s Law is not 0 when the volume flow rate out of a container with finite volume is infinite? How can this be?

7 So why is this the case?

Consider case one to be: fill the container up to a finite height and then let it empty. The time it takes will of course be finite. If we then fill it up completely so the height is infinite and let it empty, the height of the fluid will pass the level it was filled to in case one. Therefore, the time it takes to empty should be greater than the time it took for the container to empty in case one.

8 Conclusion: Does this really matter?

We derived an equation for emptying time from Torricelli’s Law and we looked at two applications. We designed a container which has equal spacing between time demarcations for a clepsydra, and we looked at what happens when you use Gabriel’s horn as a container.

The lazy persons’ container can be made, it looks very similar to a cup used for drinking.

However, before we try and construct a real Gabriel’s horn, there are a few problems we need to consider. Firstly we would need an infinite amount of material to do this. If we assume physics works, then we can’t have Gabriel’s horn made from a lamina because it would collapse, so it would need to have some thickness. Since the surface area is infinite, it would require an infinite amount of material. I am going to use proof by citation to show this is true [8].

Secondly, It might not fit in the universe. This is a really big problem, however, we don’t know yet whether the universe is infinite or just extremely large [9].

Thirdly, No one would fund something which has these big and fundamental problems, can you imagine pitching this idea and saying that we need an infinite amount of material and it might not even fit in the universe?

Lastly, and perhaps the largest of the problems, is that something has to replace the space left vacant by the fluid exiting the container, and typically this is air. For a normal shaped container like a cylinder this is no problem – just cut a big hole in the top to let the air in, but when your container is shaped like Gabriel’s horn, that’s a bit of a problem… We don’t really have a top we can cut a hole into, so the only way for air to get in is through the hole in the bottom. This would add disturbances into the flow making it a two-phase flow and that isn’t math I want to get into [10]. We also can’t just do this in space because most fluids (particularly water) don’t like it when you remove the air around them.

Note for future use of this equation. The equation is useful for realistic scenarios, but not mad hypothetical scenarios that I dream up.

9 References

1. https://www.ascsa.edu.gr/uploads/media/hesperia/146678.pdf

2. https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?id=1946

3. https://van.physics.illinois.edu/ask/listing/2251

4. https://youtu.be/2vfTwnlsrCM?feature=shared

5. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/ff/AGMA_ Clepsydre.jpg/220px-AGMA_Clepsydre.jpg

6. https://larkinthemorning.com/cdn/shop/products/trumpets-fanfare-_ coach-silver-plated-horn-44-inch-1264009019433.jpg?v=1575933266

7. https://gyazo.com/443969f349c1ecafee3ec8c4e0b06fb4

8. https://www.dummies.com/article/academics-the-arts/math/calculus/how-to-find-the-volume-and-surface-area-of-gabriels-horn-192117/

9. https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/Is_the_Universe_ finite_or_infinite_An_interview_with_Joseph_Silk

10. https://www.maths.cam.ac.uk/opportunities/careers-for-mathematicians/ summer-research-mathematics/files/Kenton.pdf

[…] Essay Competition 2024: Student (Under-18) WinnerTRM Essay Competition 2024: Adult (Over-18) WinnerTRM Essay Competition 2024: Winners […]

LikeLike