Joe Leach

For non-mathematicians (and for many mathematicians for that matter) the terms “abstraction” and “abstract algebra” will likely send shivers down your spine. However, I ask that you keep an open mind: the concepts we discuss will almost certainly feel weird at first, but, if you stick with with me, you might just catch a glimpse of the beautiful structure that mathematicians spend our lives trying to uncover. Starting with the tube map…

Look at this aerial photo of London:

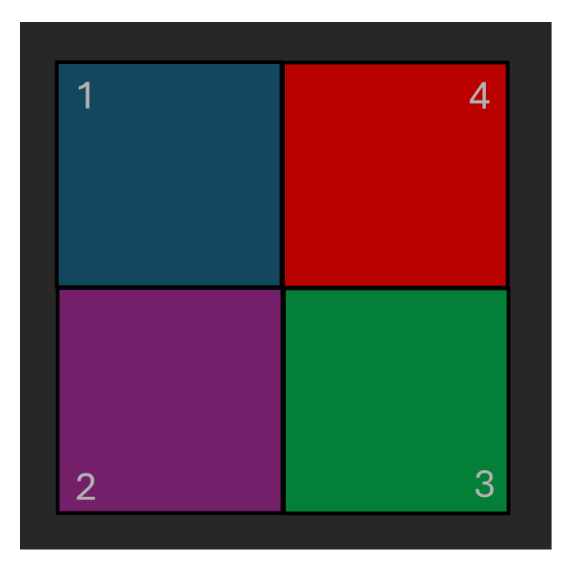

Now look at the tube map:

The observant amongst you may have realised that, despite both representing the same thing, the two images above do not share many similarities. And that’s because the tube map is of course an abstraction. It is a simplified version of reality.

Say you want to take a train from Baker Street to King’s Cross – do you need to know where every tree on the way is located? Do you need to know the position of the roads above you? Do you even really need to know the distance between them? Not particularly. So, the tube map leaves out all of that information. Take a moment to appreciate how unreadable it would be if it didn’t. This example gets to the core of what abstraction is: working out what is important to you for a given problem and what can be ignored – it allows us to take very complicated situations and relate them to something we’re familiar with.

So whilst this is all well and good, how is it maths? Well, the tube map is really just a list of stations and which other stations each one connects to. As it turns out, this kind of structure appears often in maths and we study it through the tools of a field called ‘Graph Theory’. More on that to come, but for now let’s put abstraction in the context of something unambiguously mathematical: numbers.

Numbers themselves are a form of abstraction – you can count how many of a thing you have. So whilst 3 oranges is a concept that has a real world meaning attached to it, what does 3 really mean without something to have 3 of? Well, one day someone noticed that, whether you have 3 oranges or 3 apples, if someone gives you 2 more, you’ll have 5. So, in a sense, we divorce the definition of numbers from their original context of counting objects to implement them more generally. Then, after doing our calculations in this simple, abstract world, we may reapply the context. (i.e which fruit you have 5 of). This idea is at the heart of abstraction, and starts to show why the technique is so powerful. For anyone who hasn’t been keeping up with the last few millennia of maths, it turns out that these “number” things are, to say the least, pretty useful.

Treating numbers as a “thing” in their own right and stepping away from the real world means we can develop facts about numbers in isolation, and then later apply them to real problems. This in fact reflects a general pattern within mathematics: the “pure” maths of today will, in time, become the applied maths of the future. Much of quantum physics rests on the imaginary numbers, for example, which were seen to be simply a mathematical oddity when they were first being explored in the 1700’s.

But we needn’t be that complex (if you’ll excuse the pun), even negative numbers don’t really exist in the world. You certainly won’t have seen minus 3 birds, and how could you have? That sentence was nonsensical. Minus 3 exists in relation to the natural numbers, the positive whole numbers and zero: -3 + 3 = 0. But what does this mean for counting stuff? Not a whole lot. So, without knowing it, every schoolchild in the world is using abstraction: starting initially from something familiar (3 oranges) and then moving to something abstract but that can be linked (the concept of 3). Once these numbers feel normal and intuitive, we then move onto something even more abstract that only makes sense in relation to that first abstract concept (minus 3). The mathematician – generally expected to be smarter than your average school child – simply takes this idea a little further. To them all numbers, positive, negative, imaginary, are second nature, so they delve deeper into mathematics, building the abstraction through analogies.

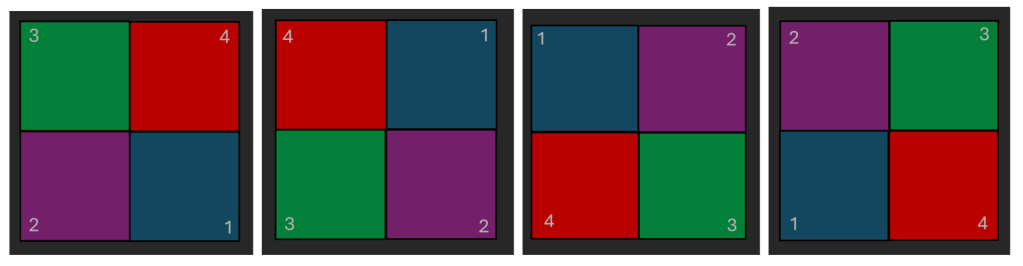

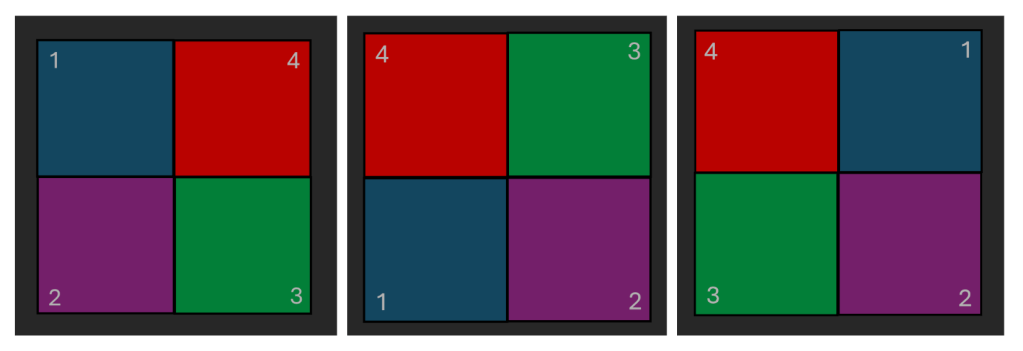

Here’s another example with a square:

What are its symmetries?

Well, we can do four reflections:

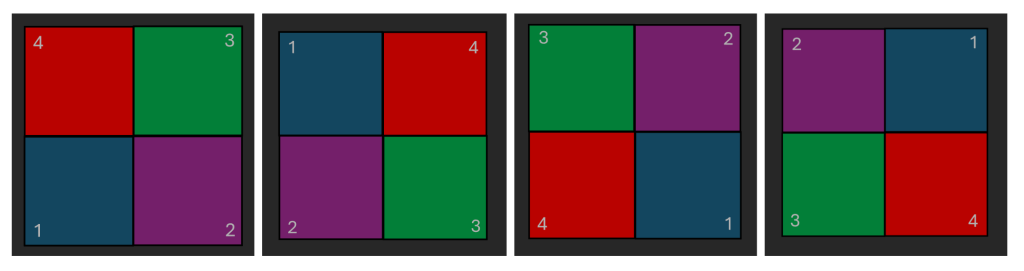

and four rotations:

to give a total of eight symmetries. Now what happens if you rotate anticlockwise by 90 degrees and then reflect through the principal diagonal? Starting from the original square on the left, we first get the middle square, and then reflecting we obtain the square on the right.

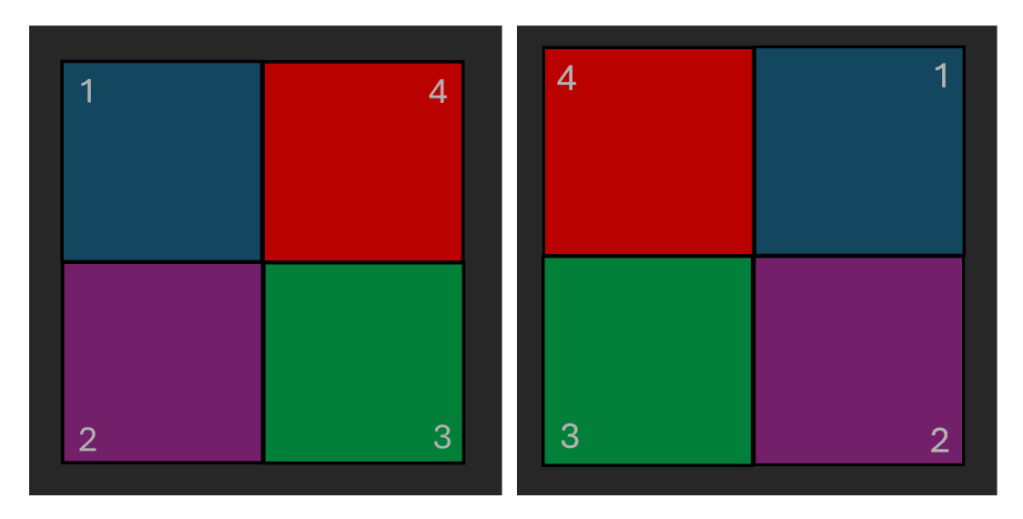

And if go back to the original square and reflect it through the vertical line of symmetry, we obtain:

Which is the same as the rotation followed by the reflection. You can now ask the question: does this work for all of the symmetries? Can we always “add” two to get another? If we can, (again, more on this in a later article) then maybe we can use some of the things we know about addition of numbers to learn things about symmetries, or perhaps even use things we know about symmetries to learn things about numbers. Suddenly the floodgates are open and the two ideas are not so disparate.

But this is far from the only example of abstraction allowing us to advance in maths. Take vectors for example. We begin by thinking of them as arrows in 2-D space, then progressing to two numbers in a column representing the “length” and “height”. Later, we might move on to 3-component vectors which represent arrows in 3-D space. Bu, thinking like a mathematician, why stop there? Obviously, we can’t visualise a 4-D arrow, but a list of four numbers? That we can – and do – work with. Another example of abstraction in action.

Hopefully this step towards the mathematical unknown is beginning to spark a little excitement in you, but still, you would be forgiven for thinking it’s all a little, well, pointless. But bear with me, there are indeed plenty of good reasons to care about higher dimensional vectors; my personal favourite starts with a story about oranges… I know this is the second time in this article I’ve talked about oranges – maybe I’m hungry? – but these aren’t just any old oranges I’m talking about, oh no… these are 8-dimensional oranges.

But first, we begin with the regular (3-dimensional) kind of orange, and more specifically, the most efficient way to pack them into a box. Given this is a mathematical problem, the box is, of course, infinitely large. The problem was first posed by Johannes Kepler in 1611 and remained unsolved until the turn of the 21st century, when a man named Thomas Hales provided the optimal packing solution.

Given our new-found taste for abstraction, the next question is naturally how far can we take this? What about the optimal packing of higher dimensional fruits? And so, in 2016 Maryna Viazovska published a (Fields medal winning) paper demonstrating the densest packings of 8-dimensional spheres (or oranges as I like to think of them). This may initially seem like a pretty useless result; I mean it’s not often you’re tasked with packing 8-dimensional spheres. But here’s the twist. This result is very relevant to something known as error-correcting code.

Computers work in bits and bytes. A byte of information is eight bits: eight 1s and 0s in a string. Since this is a list of eight numbers, we can visualise it as a kind of 8-D vector. In fact, simplifying and using our initial 2-D visualisation of vectors, we can imagine a grid with each possible combination of 1s and 0s existing as a point in space. If we find ourselves in a situation where we are expecting a 00 or 10, but the computer makes an error and instead sends 11, we know that 10 is “closer” to 11 than 00, and so it’s more likely that 10 was the intended result.

With a full 8 bits of information, the concept is the same. Only certain sets of 8-bits (points) are possible, and so if the computer gets one of the numbers wrong, the vector will point to an impossible point, and thus the computer knows that an error has been made. Furthermore, the “closest” point that is allowed is most likely to be the correct code.

Putting this all together, the fact that you can pack 8-D “spheres” with very small “gaps” means that we can create the set of possible points in a way that allows us to (very nearly) always know what the code should’ve been. For those curious about how this works, this essay explains the concepts in more detail, but the important thing to note is that once again, removing the original context and expanding definitions into abstraction yields incredibly rich results.

For vectors in particular, we’ve been studying them for a while, which means we know a lot about them, and so are always looking for ways to build connections back to them. A later article in this series will discuss a completely different way of abstracting vectors, so keep a look out for that if you want to get a taste for just how deep this rabbit hole goes…

That’s probably enough to get your head around for now, so to summarise: this has been a whistle-stop tour of some of the ways mathematicians think about abstraction, as well as an attempt to exemplify why it might be useful to abstract away bits of information, or to use abstraction to extend definitions and to push ideas well past what they were originally intended for.

Ultimately, abstraction allows us to build intuition for things that we may not deal with in everyday life, and to look at things we do deal with commonly, like symmetry, through a different lens, opening up a whole new mathematical toolbox. This is a theme throughout mathematics – if you ever look at a concept in maths and it reminds you of a completely different concept, follow your nose. It might just lead you to a paradigm shifting discovery.

Read the next article in the series here.

*Image from whatdotheyknow.com

[…] the first article I hinted towards there being more to say about the maths of the tube map, and as a man of my word, […]

LikeLike

[…] 1: The Path Towards Higher Mathematics is Guided by AbstractionArticle 2: Abstraction and Graph Theory with […]

LikeLike

[…] let’s leave numbers behind and think about a square and its symmetries. You may recall from the first article that there are eight in total: four rotational symmetries and four reflectional symmetries […]

LikeLike