Yu Xiao

In the previous article “Maths Proofs Without Words” we introduced the visual interpretation of the Fibonacci numbers: the (n+1)th Fibonacci number Fn+1 is equal to the number of ways to tile a board of length n (called an n-board) with squares and dominoes. This visual interpretation gives a way to explore mathematical properties of the sequence by simply playing with the squares and dominoes. In this article, we will explore some creative techniques to prove Fibonacci properties using such visual proofs.

Let’s start by breaking the boards! For example, suppose we wanted to break a board of length 4 at cell 2 (where the breaking occurs at the right-hand edge of the cell as shown in the figure below). Note that if cell 2 and cell 3 are covered by one domino, then the board is unbreakable at cell 2. Otherwise, the board is breakable at cell 2, and we can break it into two shorter boards of length 2.

Now we generalise: let’s try to break a 2n-board in the middle, at cell n. If it’s breakable, then we get two n-boards, so there are fn * fn ways to tile these two n-boards. If the 2n-board is unbreakable at cell n, then there is a domino that covers cell n and cell n+1. As shown in Figure 2, in this instance we get two (n-1)-boards, so there are fn-1 * fn-1 ways to tile these two (n-1)-boards. Since cell n is either covered by a domino, or it isn’t, this means the breakable and unbreakable tilings are two disjoint cases, and their union is exactly all the tilings of a 2n-board, so fn2 + fn-12 = f2n.

In fact, we can break the board at any point we want, not necessarily the middle of the board as in the above examples. Instead, suppose we break an (m+n)-board at cell m. A similar proof will give us the formula fm+n = fm * fn + fm-1 * fn-1, as shown in Figure 3.

The central idea is all of these proofs is to condition on one particular property of the tilings, thus dividing all tilings into disjoint (non-overlapping) cases. We can then count the number of tilings in each case separately, and then add up all the cases to get an equation. Besides breakability, we can condition on many other properties of the board, such as the position of the last square, the number of dominoes in the tiling, and so on. Different conditions will give us different formulas. I highly recommend playing around with this concept yourself to see what you can discover!

Let’s look at another example: this time instead of breaking the boards, lets look at what happens when we extend or shorten the boards. For example, given an n-board, we can add a square at the end to get an (n+1)-board, or delete the last square to get an (n-1)-board. But how do we build up rigorous maths proofs from such operations? The idea is to establish a bijective map, or a one-to-one correspondence.

Given two sets A and B, a bijective map matches each element of A with a different element of B, as shown in Figure 4, and each element of B has a corresponding element of A. If there is a bijective map between two sets, then the two sets have the same size.

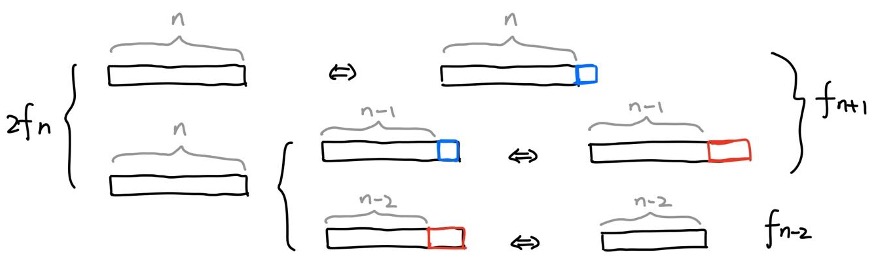

Take the proof of 2 fn = fn-2 + fn+1 as an example. The two sets we are considering in this problem are: Set A, which contains two copies of all tilings of n-boards, and Set B, which contains all tilings of (n-2)-boards and (n+1)-boards. Set A has size 2fn, and Set B has size fn-2 + fn+1. If we can establish a one-to-one correspondence between the two sets, then their sizes should be the same, so the equation 2fn = fn-2 + fn+1 follows.

To do this, let’s manipulate the two copies of n-boards and try to turn them into (n-2)-boards or (n+1)-boards. For one copy, we can simply add a square at the end to create an (n+1)-board. For the other copy, there are two possible cases for the last tile. If the last tile is a square, extend the square to a domino to create an (n+1)-board. If the last tile is a domino, delete the domino to create two (n-2)-boards.

Notice that a bijective map is necessary, so when we are extending or shortening the boards, it’s important to check that we can create all possible tilings and we can reverse the operations. In this proof, we create (n+1)-boards that end with a square by adding a square at the end, and we create (n+1)-boards that end with a domino by extending the last square into a domino. Together we have all possible (n+1)-boards. Furthermore, we can easily reverse the operations, and create two copies of all n-boards (Set A) from all (n-2)-boards and (n+1)-boards (Set B). Therefore, we have established a one-to-one correspondence between Set A and Set B. The proof is complete.

By breaking, extending and shortening the boards, we’ve found two more formulas involving the Fibonacci numbers, and there are many more. For example, what if we have three copies of n-boards? How should we extend or shorten them to establish a bijective map? I encourage you to play with the squares and dominoes for yourself – do anything you want to the boards – and you will find many interesting Fibonacci properties. Don’t forget to verify the formula you get with a calculator, because no matter what we do to the tilings, our eventual goal is to express the result rigorously.

There’s even more to come in article 3 – see you there!

References:

- Proofs that Really Count by Arthur T. Benjamin and Jennifer J. Quinn.

[…] operation in turn corresponds to a beautiful mathematical formula. Playtime continues in the next article where we derive even more beautiful formulae using nothing more than squares and dominoes – see […]

LikeLike

[…] represent the number of ways to tile a board with squares and dominoes, and how we may explain interesting Fibonacci properties using visual proofs. In fact, there are many more sequences hidden in the patterns squares and dominoes, such as the […]

LikeLike